There are so many different religions. How do we know which one is true?

This, C.S. Lewis says, prompted his own adolescent atheism. It is a problem still posed by the new atheists: “You don’t believe in Zeus, do you? You yourself are atheist about a thousand gods. So why arbitrarily believe in this particular one?”

It is, in part, Lewis notes, a false problem. Because it is always the case that, on any given topic, only one theory will be true. The rational conclusion is not that they are all false.

What remains is how to decide that X is the correct theory, and not any of the others.

Let’s do the exercise.

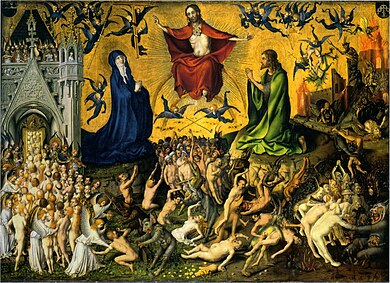

Begin with paganism. Dawkins and the like are ignorant to claim that Christians do not believe in Zeus and other pagan gods. We do. But they are amoral and ill-disposed towards mankind. Real pagans will agree. They are, in other words, ambient spirits, daemons, genii. The great thing about our god, Yahweh is that cleaving to him alone takes care of possible harm from them.

And the proof is in the pudding, and was historically: when was the last time you were demonically possessed?

So sticking with paganism when Christianity is on offer is like seeing your house in flames, and refusing a fire extinguisher. Paganism is simply untenable, and melts like the winter snow, wherever Christianity appears.

What about Judaism? A Christian has no reason to argue against Judaism: Jesus didn’t. Judaism is a covenant between Yahweh and the Jews. It remains in force; God does not break promises. But Christianity is the covenant offered to all mankind; there is no Jew nor Greek in Christ. So if you are not born Jewish, why not embrace it instead, while continuing to honour and enjoy your own cultural traditions? Even leaving aside the good news of the incarnation.

What about Buddhism? Buddhism properly has no cosmology, and no dogma. The Buddhist dharma or “truth” is a set of spiritual practices. You do them, and experience reality for yourself. There is no call for a Christian to agree or disagree. One can, as Leonard Cohen demonstrated, be both a devout Jew and an ordained Buddhist monk. Just as anyone in China can be at the same time a Buddhist, a Taoist, and a Confucian.

Hinduism is similar. It is simply a selection of hypotheses about the divine. It has no dogma. A Christian is free to agree with some things and disagree with others, just as is a Hindu. I read the arguments, and come down on the side of the devotional Vaishnavites—the Krishna cycle looks to me like a hypothesis of the Christ. Ramakrishna’s argument for devotional monotheism, “I want to taste sugar, not to be sugar,” I find powerfully persuasive.

Confucianism is a moral code. I can, as a Christian, endorse it completely.

Leaving the pachyderm in the smoking room: Islam. Here there needs to be a straight choice. Either Islam, with its insistence on the indivisibility of God, is right, or Christianity is with its Trinity and incarnation. For Islam arose more or less in direct dissent from Christianity, after it.

A Turkish tour guide volunteered to me that Islam has the best claim to truth, precisely because it arose after all the other major religions. Like science, religion has progressed.

But, as I did not respond, not wanting an argument, by this standard, Islam too must defer to Bahai, or Sikhism, or Mormonism, all of which arose after Islam. And, of course, if truth keeps progressing, this necessarily means we never arrive at truth.

There is something to be said, instead, for the test of time. Most recent is not best in the Humanities generally: Stan Lee is not proven to be better than Shakespeare because he wrote more recently.

If the argument is that these more modern faiths are less likely to be true because they are so much smaller than Islam, then size becomes the standard. And Islam must cede the field to Christianity, which has twice the number of adherents.

It seems reasonable at first thought to suggest that unity is a necessary essence of the godhead; but, as Hindu philosophers too have realized, unity is meaningless without diversity. And a God that did not include both in his own essence, is therefore not a supreme being. He is an incomplete being.

A Muslim will cite the Quran as authority that God is one and indivisible. But that is of course circular: one accepts the Quran’s authority only if you are already a Muslim.

The Muslim will respond, perhaps, that the supernatural beauty of its language, and its ability to accurately prophesy subsequent science, serves as proof of the Quran’s divine origin. I have seen the short monographs repeatedly making this argument.

I cannot judge for myself the beauty of the language, not reading Arabic. While beauty is an aspect of the divine, I think we all accept, including Islam, that the Devil too can use beauty for his purposes. Consider the image of the female “vamp.”

.jpg/250px-Lilith_(John_Collier_painting).jpg) |

| Lilith, the lovely mother of demons. |

And if its ability to accurately prophesy things it cannot know by natural means is the test, surely it is disproven if it is inaccurate on things it could know. For example, the Quran is under the misapprehension that the Christian Trinity is Father, Son, and Virgin Mary. It further apparently thinks that the mother of Jesus was Mary, the sister of Moses.

William Lane Craig bases his rational Christianity on the empirical evidence for the resurrection. I can agree with him that in historical terms the evidence for the resurrection is strong. But that still feels to me faint praise: the empirical evidence for anything in the ancient world is slight. The last two mass readings, from Luke, speaking of Jesus’s birth and childhood, both include the note “Mary pondered these things in her heart.” This is a reminder that everything we are reading here depends on only one witness, Mary. Not strong evidence in court. While the evidence for the resurrection is much stronger, it is still surely open to forgery over the ages.

My thinking instead is as follows: first, it is undeniable that God exists. This can be proven in a dozen different ways, with a dozen sound logical arguments. Second, God must by definition be all good. Third, an all-good God would not leave us without guidance. He would want to incarnate among us to show himself to us. He would, fourth, not hide the truth: he would make it obvious to anyone who sought sincerely. Accordingly, the best claim to truth is held by the expression of his intent that is most widely geographically distributed and advertised as such.

Which leads us to Christianity, and, more specifically, Catholicism.

At the same time and by the same token, other faiths, such as Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, or Taoism, must have enough of the truth to be sufficient for the sincere seeker, as not everyone will have been exposed to Christianity.

And, as we have seen, they mostly agree.

.jpg/250px-Lilith_(John_Collier_painting).jpg)