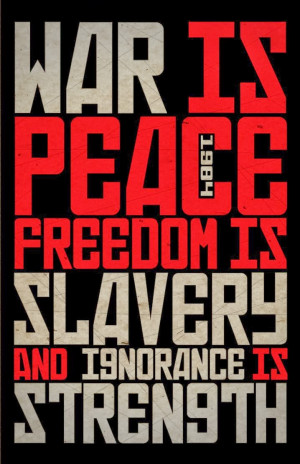

Most of the world is mad. Most of the world is in denial of reality.

I have lived in more than a few cultures now, around the world. As an outsider, it is easier to see collective delusions. Koreans think all evil comes from foreigners, especially Japanese. Arabs commonly believe the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Americans, whether conscious of it or not, tend to think the rest of the world does not really exist. Chinese think the current authority is always, necessarily, right. Don’t ask me about Canada. That would take too long.

All the countries I have lived in are insane except for the Philippines. I suspect from visits that Ireland and Italy are also sane. Although, counter to this, Italy did go with fascism not that long ago.

I spent many years in higher education, naively thinking that there I would find truth, or at least the search for truth. But, as with most things in this fallen world, the reality was the reverse of the claim.

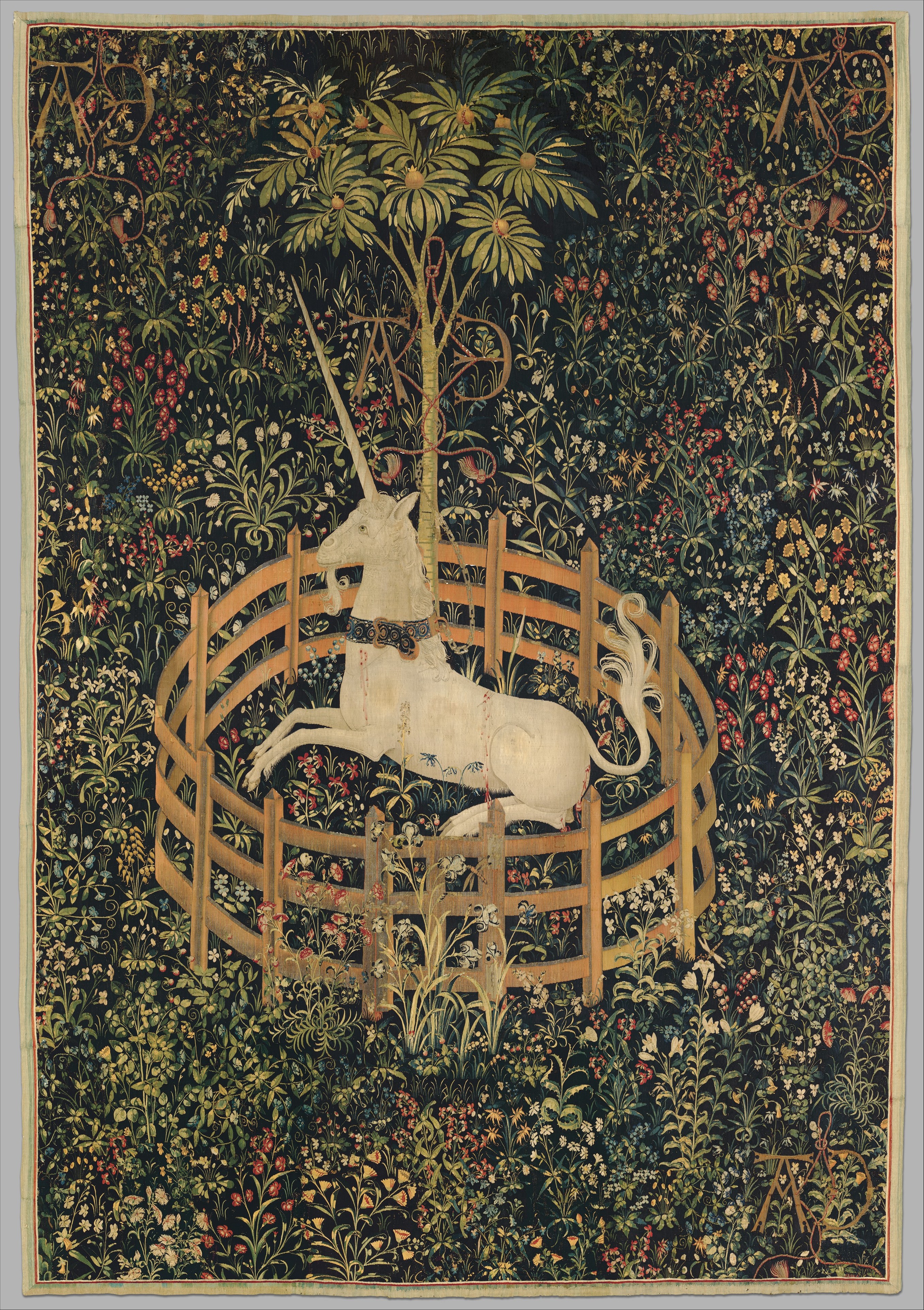

Example: in first year philosophy, the lecturer discounted this or that philosophy with the statement that, by this premise, one would have to believe that unicorns are real. “But of course, unicorns are not real,” Case closed.

Wait a minute, I thought even at the time. That’s begging the question.

How about that: a philosophy lecturer teaching a logical fallacy.

But then, the philosophy class never taught us to detect logical fallacies of any kind. No class I ever took did. Why not?

Unicorns are, of course, real. They are not physical. That is not the same thing.

Example: when I formally studied the New Testament, all scholarship began with the premise that any miracles in the New Testament were lies and inventions; our goal was to get to the “real man,” Jesus of Nazareth, an ordinary carpenter. And when I studied the life of the Buddha, the premise was the same: the goal was to recover the “real” historical man behind the supposed legend.

But this is tautological. If Jesus is divine, miracles are to be expected. The miracles are recorded to prove his divinity. And the same for the Buddha.

Example: in the history of philosophy, there are dozens of proofs of the existence of God. Nothing could be more firmly established. Yet these proofs were never directly addressed in philosophy classes, nor in nine years of formally studying religion. Instead, they were literally ignored even when they were plainly present in the texts being studied, and the existence of God was presented as a highly dubious and arbitrary matter of “faith.” One was supposed to look down on anyone who so professed as an intellectual weakling. As someone who rejected “reason”—even though reason evidently required the opposite, the admission of God’s being.

Example: William Blake’s religious ideas are essential to understanding his poetry. They were his core interest and intent. Understanding his religious beliefs is essential to understanding Yeats’ poetry. These two are arguably the greatest poets in the English language. Studying literature for nine years, I noticed that Blake and Yeats seemed to be largely avoided, at least in comparison to their merits. And when they were discussed, their religious beliefs were ignored. What, I wondered from an early age, was going on?

The case was most obvious with Blake and Yeats; but it was also obvious with other poets. Gerard Manley Hopkins was given short shrift, and when his “terrible sonnets” came up, the conventional claim was that his suffering was no doubt due to his being a devout Catholic. Shakespeare’s religious views were generally ignored, even though it is impossible to make sense of Hamlet without them. Instead, that play was just declared a “problem.” Oscar Wilde’s Catholicism was ignored. And on and on.

Similarly, the curriculum always seemed to concentrate on poets’ early work. The Romantics conveniently tended to die young; but we also rarely looked at the later poems of Eliot, or Auden, or Blake, or Ginsberg. I assumed for a long time this was because poetry was a young man’s game, like mathematics; that the gift usually faded with age.

But this makes little sense. Poetry is mostly about insight, into the human psyche and the human condition, and in the natural course, insight into life and human nature expands with age. It’s a thing called wisdom.

Rather, I come to conclude that the later writings of the greatest minds have generally been avoided because in our later years we become more concerned with metaphysical insights and speculations. In youth, we are biologically driven to focus on sex and reproduction. In age, these distractions lessen. We start to speak truth; people do not want to hear it. Aged poets become awkwardly religious. We’d rather talk about sexual longing.

We deny the “supernatural” or metaphysical out of hand. This is illegitimate. You have not demonstrated that it does not exist: you have just closed your eyes and stuck your fingers in your ears and begun to sing loudly to yourself. You are in denial.

And denying the supernatural is not honestly possible. Man is supernatural in his essence: “nature” is, literally, what exists where man is not present.

All along, through my years of academic study, I knew perfectly well that there were metaphysical realities. That is why I wanted to study religion and literature in the first place: because these realities were denied everywhere else. Yet I was compelled by the pressures of social authority to hold my tongue. If I said unicorns were real, would I be declared mad? Was I, in fact, mad? This used to be a real fear, causing me immense anxiety. Chronic anxiety, for which I had to take tranquilizers and anti-depressants.

Why is everyone in denial of the self-evident?

Guilt. We must control and deny reality, because reality is dangerous to our self-esteem.

Everyone is aware of their sinfulness, even if we are sinful to greater and lesser degrees. And there are two approaches to an awareness of guilt. Deny and be damned, or repent and be saved.

The majority choose denial.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/59134265/bozo_RIP_getty_ringer.0.jpg)