|

| To be remembered, now and in days to come, wherever the maple leaf is flown. |

Politics is downstream from culture; and culture is downstream from religion. This political world is in the hands of the Devil. So should we really care too much about politics? Does it even make a difference?

It does. Not usually. Usually, politics is just about reading the polls and running to the front of the parade. But when there is an exception, it is magnificent, and worth attention even as art. For a current example, Ukraine might not have held out against Russia in the early days of the war had Zelensky not been in charge. Another leader might have taken the offer from America of a quick flight to safety. Zelensky went before the cameras instead, and said “I need ammunition, not a ride.” That alone is worth a statue in every town square. He has been similarly eloquent since in scaring up material support from the West.

And the results of his speeches are likely to be profound for the future lives of citizens of Ukraine, of Russia, and quite possibly of China, Taiwan, Iran, and the rest of the world. The right man with the right words at the right time.

Churchill is a similar example. His speeches and his resolve during the Second World War held things together when another leader might have sought terms with Germany after Dunkirk. As Chamberlain did, and the French. Then where would we all be?

From these examples, we see that good politics is actually a form of art: rhetoric. Both Churchill and Zelensky are in fact certifiably artists, quite apart from politics. Churchill won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Zelensky was a popular television comic.

The military apparently knows this. A friend went through the American Air Force Academy’s officer training. He says the main emphasis was on giving a speech.

One can say that it is art, and not politics, that makes a difference. But then one must note that the best politics is itself art. One can miss a Ralph Klein, or a John Diefenbaker, or a Boris Johnson, just for the fun of watching them perform, quite apart from their policies.

Two things are necessary for good politics, rare as it is, and they are the same two things necessary for art: skill at communication, and principle. Or, put another way, something important to say, and the ability to say it well. This is the difference between art and mere craftsmanship. Or between being an artist and being a madman.

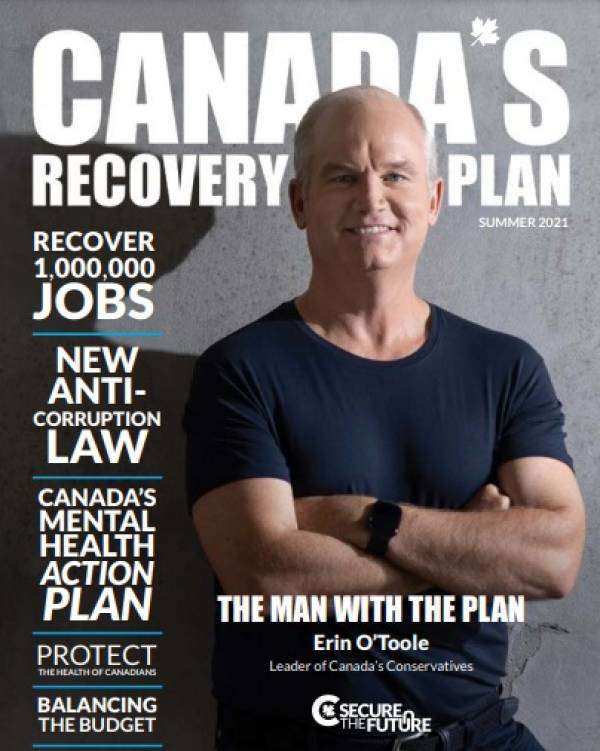

Pierre Poilievre excites me on the Canadian scene currently, because he has exceptional rhetorical skill. You can see it especially in his postings to social media. He may not hold to principle; but so far the prognosis looks good. The contrast with Erin O’Toole is dramatic. O’Toole seemed to have no principles, and then did not speak well. He was bad enough to be offensive, to insult one’s intelligence for having taken the time to listen. Andrew Scheer might have had principles, but who can tell? He was inarticulate when asked to express them.

Donald Trump in the US, and Boris Johnson in the UK, are interesting and tragic studies of just falling short. Both have immense rhetorical skills. This gave them great promise. Trump is given too little credit for his artistic talents. He can speak extempore for two hours, and hold an audience enthralled. His short epithets for opponents are, in their way, poetry.

Yet both fail on lacking clear principles, lacking a vision; making them mere craftsmen. Boris was great until Brexit was accomplished, and then floundered. He was all dressed up, with no idea of where to go. Trump was great at expressing the themes of “America First” and “drain the swamp,” yet he seems to have been ineffective at draining it; while his choice of foreign policy advisors seemed inconsistent. This may have been because of internal opposition; but I don’t buy it. The problem was that his true love was the art of making a deal. As part of this deal-making process, he would talk a hard and principled line, then compromise. The initial principle mattered less than getting the deal. Good business, but not good politics; because uninspiring. It leaves the impression of moral chaos.

A similar tragic failure is John Diefenbaker. He was wonderful to listen to, always entertaining, often compelling, often right, but he quickly came to exude the same sense of chaos as Trump and Johnson do. He was a heavy cannon, but a loose one. He managed the Canadian Bill of Rights, and then was not sure what to do.

Adolph Hitler and Benito Mussolini were also artists, and this was probably the source of their success. They knew how to communicate. Hitler’s speechifying was famous. But they were also lousy artists; and not just, like Johnson or Diefenbaker, because they lacked principles; although they did. William L. Shirer, who was there, noted that Hitler would say completely different things with equal conviction depending on his audience. For Mussolini, Fascism was mostly whatever the moment seemed to require. They were also bad at art, in the sense of relying on cliché and cheap thrills. As a visual artist, Hitler’s drawings were always cliched scenes, of the sort you might once have bought in a Woolworth’s painted on felt. Not good enough, famously, to get him into the Vienna Art Academy. Mussolini wrote short stories; but they are dime novel stuff, relying heavily on cheap thrills and lurid descriptions of violence. They were the sort of artists who do often achieve mass appeal with emotional junk: the drawers of paintings of kittens with big eyes and the writers of formula romances for Harlequin.

So too with their political rhetoric: full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Justin Trudeau is frighteningly cut from the same cloth: an incompetent wannabe actor. And his wife is, interestingly, a wannabe singer of about the same calibre. The class of wannabe artists is crowded with narcissists. The narcissist will naturally want to think of himself and be thought of as an artistic genius. But he will lack the necessary insight or self-knowledge. Indeed, he will be terrified of insight or self-knowledge.

Anothergreat political artist was Ronald Reagan. Reagan, of course, learned his craft as an actor, and a real, successful actor, not a poseur like Trudeau. Granted, he was a better politician than actor. Acting is harder and a higher-level skill than politics. But his skills helped bloodlessly end the Cold War, and ushered in a new golden age for America, after years of apparent decline.

Margaret Thatcher did about the same, at about the same time, for Britain. Again, it was largely due to attention to rhetorical skills as well as to firm principles. She worked hard at rhetoric, learning to lower her voice, for example, to sound more authoritative. She, or her speechwriters, are responsible for a number of lines that are now immortal, like “The lady’s not for turning.”

Acting ability and experience was the secret of John Paul II’s papacy as well. Pope Benedict, the more learned and the better-grounded man, really John Paul’s mentor, lacked this talent, and so sailed into controversy. Which sadly wore him down. Pope Francis, unfortunately, lacks both Benedict’s vision and John Paul’s acting skills.

Thomas D’Arcy McGee in Canada, and Daniel Patrick Moynihan in the US, are other examples of brilliant politicians. Neither rose to the very top of their profession. Yet this, I think, was because both were more interested in doing good than in personal power. Principled men, they would rather have been right, as they say, than president. This seems to be especially an Irish thing. One thinks also of Grattan O’Leary, Bryce Mackasey, Eugene McCarthy, or of W.B. Yeats’s political career.

Although too little credited, and still too little listened to, D'Arcy McGee invented Canada.

Pierre Trudeau was another brilliant politician, in contrast to his son. He himself once remarked that he saw the job primarily as that of an actor. He was magnificent on the principle of federalism and against separatism, although he lost direction once this matter seemed settled. As it happened, separatism was such a dominant issue during his political career that few in Central Canada noticed how erratic and frivolous he was on other topics. Folks out West did.

The mention of Moynihan, McCarthy and Trudeau, officially on the left, perhaps serves only to throw into relief the fact that most of the politicians I cite as great seem to come from the right side of the political spectrum. Is this bias on my part?

I think not. It is the principle thing. Pretty much by definition, to have enduring principles means to be conservative. To be “on the left” means, broadly, to be calling for change, being subject to whatever winds might blow. Anyone who still held sincerely to the beliefs of the left as they were thirty years ago would now be denounced by the left as an extreme right-winger. Ask Elon Musk, or Joe Rogan, or Jordan Peterson, or Ronald Reagan, or Joseph Ratzinger. So leftists might be rhetorically skillful, but almost by definition lack a consistent vision. “Change” is not a vision. It is a kaleidoscope.

And if you lack a consistent vision, it is even hard to be rhetorically compelling. It is not just that people are liable to notice you were saying the opposite until recently. If it is really good, fellow leftists will remember it to condemn you for it a few years later.

This is one reason why, to look for any real change, we must look to the right.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66910683/XV___The_Devil___VAR.0.png)

_-_James_Tissot_-_overall.jpg)

.jpg)