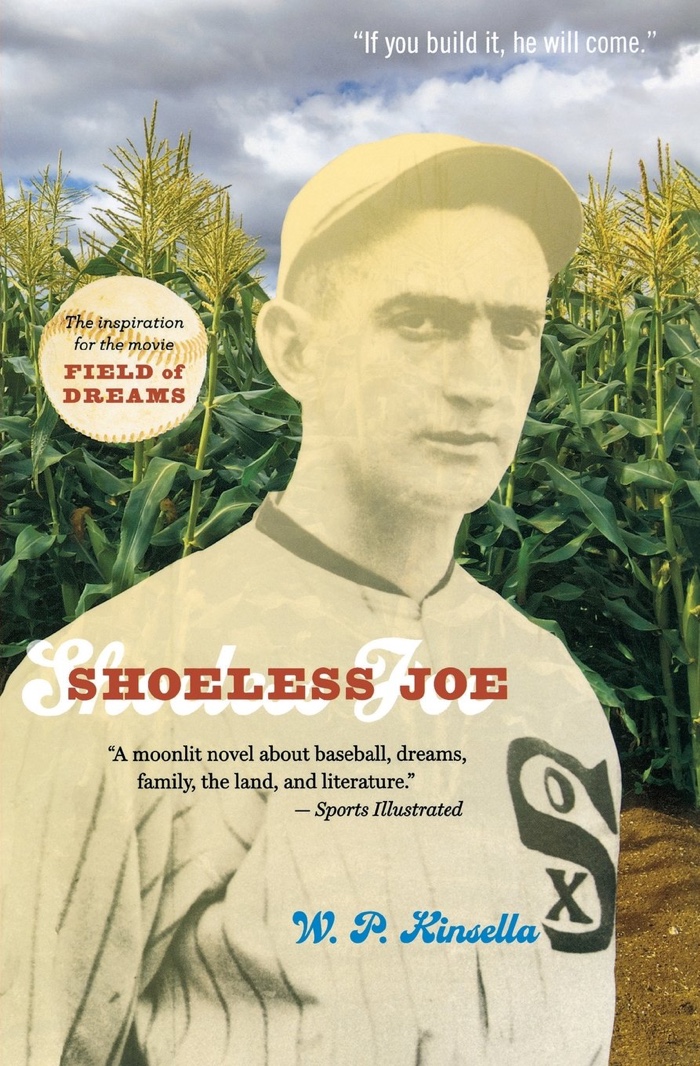

W.P. Kinsella’s Shoeless Joe is magnificently written. It is a pity it is Fascist.

It shows the appeal of Fascism; which is worth understanding. After all, how did it attract so many in the early and middle years of the last century? It must have had something going for it.

It seems to be especially appealing to artists. The artistic movement known as Futurism was in the Fascist vanguard. Ezra Pound was famously drawn in. Gabriel D’Annunzio, the original Fascist dictator, in Trieste, was prominent poet. Hitler was a wannabe painter, Mussolini wrote short stories. Fascism made a strong appeal to the imagination. As does “Shoeless Joe.”

“If you build it, they will come.” If you just wish for a thing strongly enough, believe in it strongly enough, it will happen.

In other words, the triumph of the will.

Like Fascism’s elevation of the volk and the volkish, Shoeless Joe elevates traditional American folk culture to sacred status: Kid Scissons even, on the point of death, preaches a kind of Sermon on the Mound.

“I take the word of baseball and begin to talk it. I begin to speak it. I begin to live it. The word is baseball. Say it after me,” says Eddie Scissons, and raises his arms.

“The word is baseball,” we barely whisper.

“Say it out loud,” exhorts Eddie.

“The word is baseball,” we say louder, but still self-consciously.

“The word is what?”

“Baseball …”

“Is what?”

“Baseball…”

“Is what?” As his voice rises, so do ours. “Baseball!”

He pauses dramatically. “Can you imagine? Can you imagine?” His voice is filled with evangelical fervor. “Can you imagine walking around with the very word of baseball enshrined inside you? Because the word of salvation is baseball. It gets inside you. Inside me. And the words that speak are spirit, and are baseball.”

At the same time, our narrator is scornful of conventional religion.

The great advantage of seeing life as a game is that there is no morality involved. One only seeks to win.

There is an underlying conflict in the book: the narrator’s brother-in-law wants to buy his farm. He does not want to sell.

And, tellingly, morality is not involved. Ray, the narrator, attempt no moral case that his desire to stay on this farm is more important than brother-in-law Mark’s desire to incorporate the farm in a more profitable larger section. Rather the reverse: he has not kept up with his mortgage, his brother-in-law offers attractive terms, and his brother-in-law will be financially ruined if he refuses. Morality is clearly not the point. It is only a matter of winning the game, again, a triumph of personal desire, of the will.

To cap it off, Mark’s business partner, the true villain in the tale, is an accountant named Bluestein. A suspiciously semitic-sounding name. A foreign, cosmopolitan presence in an Iowa wheat field.

The core premise of the novel, the core premise of Fascism, is also the core premise of postmodernism, seen for example in current gender ideology: there is no objective reality, and we are free to construct and impose our own narratives.

It is pretty liberating. But Kinsella himself seems to as much as admit that The Voice speaking to the narrator throughout the novel is in fact the Devil.

Kinsella killed himself by assisted suicide in 2017.

No comments:

Post a Comment