|

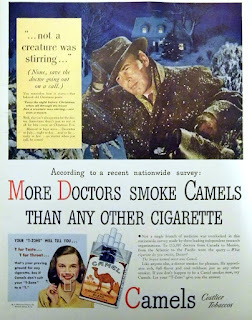

| Photographed in an antique shop window. Is it live, or Memorex? |

There are only two kinds of discoveries in the social sciences: those that do no more than confirm common sense, and those that are wrong. The latter is more common.

This study is probably correct. It suggests that bullies have high self esteem than the average person and are less likely than others to experience depression. So much, indeed, is common sense. Unfortunately, it goes directly against everything social science have been telling us for a generation or two. For at least that long, we have been told that bullies and abusers act as they do because they were themselves abused in the past, and because they have low self-esteem.

Teaching and parenting practice has, of course, been altered, sometimes forcibly altered, to reflect this for that same two generations, always sparing the rod in hopes of more perfectly spoiling the child. Everything a child does is now awesome. Nothing a child does can be punished in any meaningful way.

No surprise if we now have a much bigger problem with bullying in schools. We of a certainty also have it in the wider world of work, in society, in marriages, in life in general.

And we paid large sums to get screwed in this way.

What's worse, we've been told for about the same time to work on our and our children's “emotional intelligence.” Sounds good, put in that way, but it really means learning to falsify your own true feelings while manipulating those of others. In other words, training to be a proper psychopath.

Here's another instance of this academic game at work. Some time ago, a prominent paper came to the conclusion that there was never any significant discrimination against the Irish in America, and few if any “No Irish Need Apply” signs or ads. The Irish had simply imagined the whole thing. Now, a high school student—a high school student—has managed to disprove the claim comprehensively, simply with a bit of web searching.

A bit of web searching.

How, you might ask, is this possible? How can an academic paper become so widely accepted while making such extremely improbable claims, and on the basis of so little evidence?

It is really quite simple. Academia is set up to make this happen. Imagine if the original paper by the reputable history professor with the Yale Ph. D. had researched the record thoroughly and discovered that, yes, as everyone had always assumed to be true, discrimination against the Irish in America was widespread in past generations, and there were a good number of signs denying them employment. Would there then be a publishable paper, simply confirming what everybody already knew? Probably not. But if you can put out a paper that seems to show that what everybody thought was wrong—then you get it published, get tenure, get a lot of attention. You have discovered something!

All that really prevents this is the sheer honesty of individual academics. Unfortunately, morality has become unfashionable in such circles. Indeed, academics as a group, as a class, have a vested interest in promoting this kind of behaviour, rather than censuring or preventing it. If a field as a whole seems to produce no new discoveries, can produce nothing the general public doesn't already know, it is hard to justify its very existence. Why take a Ph.D. in it, if you learn nothing? Why pay someone to teach it, if he has nothing to teach? Thus, it becomes important for any field to consistently violate common sense. This is probably, on the whole, not a good thing.

Yes, there is the risk that someone will try to reproduce your results and find them wrong; as happened here. But the same problem applies: merely repeating and confirming someone else's study is not generally publishable. So others rarely do it. The high school student's paper made waves because the original paper, arguing that the Irish had not been discriminated against, had become so widespread among academics to have become, itself, a new received wisdom. At this point, “revisionism” begins to pay dividends. And the cycle begins again.

Just as a clock that has stopped dead will still be accurate about twice a day, so all these crazy ideas emerging from the academy probably get disproven eventually. However, what we are witnessing is not a quest for truth or knowledge, and alarmingly little get added year by year to the store of human knowledge. In the meantime, a great deal of damage gets done.

It is worst in the social sciences, because they are based on incoherent premises—primarily, an insurmountable observer paradox. But the same also applies in the humanities and in the hard sciences. The difference is that the social sciences emit nothing but this static; humanities and hard sciences do also sometimes produce valid results.

Even so, anyone who has lived long enough and made some effort over their lives to follow medical advice will surely have noticed the pattern. Sugar will kill you. It will make you fat. You must take artificial sweeteners. No, wait, artificial sweeteners will kill you and make you fat; you must take sugar. No, they are quite safe; sugar is bad and will make you fat. You must get more sunlight for vitamin D. You must stay out of the sun or get skin cancer. You must get more sunlight for vitamin D. You fools! Why have you not been listening to us experts? Cholesterol is bad for your heart; cholesterol is good for you. Eggs are healthy; eggs are unhealthy; eggs are healthy. Aspirin is dangerous; safer to take acetaminophen. Acetaminophen is dangerous; safer to take aspirin. Statistics at least tell us medicine does make some progress; technology proves that hard sciences make some progress; but there is obviously still a huge amount of static involved.

This is one reason why I love the Catholic Church. Of all human institutions with intellectual pretensions, it seems uniquely immune from this disease. All other human “knowledge” seems built on sand; it alone is built on rock.

No comments:

Post a Comment