|

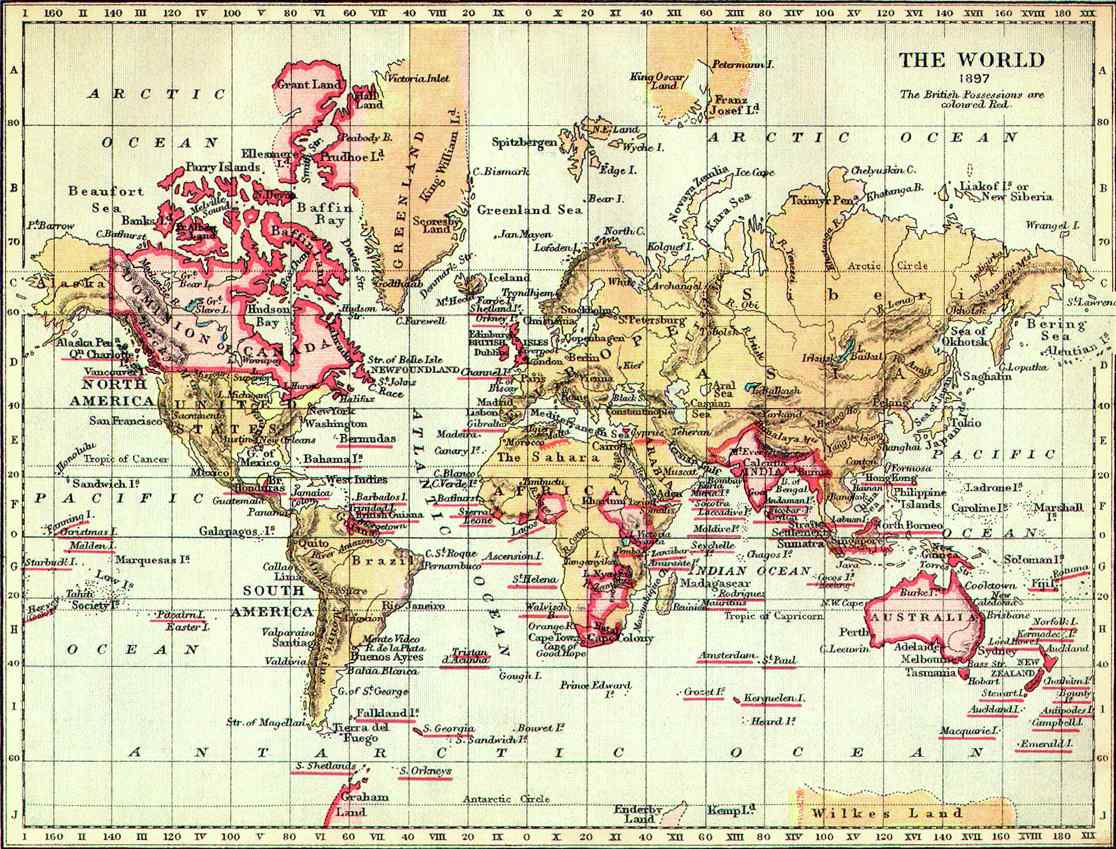

| Big Pink. |

With Brexit, a union of the Anglosphere becomes more plausible. And you hear more mention of it. Most British commentators, true, do not include the US in the proposed entity, as I would. This is perhaps understandable, as the US would completely dominate any such union. The UK does not like being number two.

But then let's play the ball where it lies: without the US for now. It seems to me that the concept of such a union still makes mighty good sense for the potential players: most obviously, Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand.

First and for all, of course, there is the benefit of free trade, and the free movement of people. Canadians could choose to move to and work in Australia, and Britons in Canada. Canadians who look with envy at the greater career opportunities in the huge American market, especially, should appreciate this.

For Britain, there is secure access to the natural resources of Canada and Australia. It makes more sense for the UK to establish free trade in this direction than with Europe, because European nations are much of a muchness; they all more or less offer the same competitive advantage, a large skilled labour force, and so are natural competitors. By contrast, Britain's strengths and Australia's are more complimentary: Britain has a large skilled labour force, and strong, established service industries, but lacks Australia's natural resources.

It also makes more sense in cultural terms, of course, for Britain to reach hands across the sea than to stick with Europe. Its culture, and especially its political culture, is far closer to that of Canada than to that of Italy. Moreover, Britain is by tradition and geography a maritime trading nation; its natural ties are not the land ties and the ties of proximity that drive the rest of the EU.

For Canada, the great allure is, as has always been the core of the Canadian experience, a counterbalance to the strong centrifugal force of the USA next door. As part of a Commonwealth Union, Canada would be, unlike with the US, and indeed from then on in dealing with the US, much more of an equal partner. Canada has a vast territory that, if ever challenged, it does not have the manpower to protect. Now, it relies entirely on tacit US protection. That is beneath the dignity of a great nation. That is the state of being a colony. Better a formal military alliance with Britain, which does have the manpower.

Moreover, Canada’s security needs fit Britain’s capabilities like a glove fits a hand. Britain is by tradition a naval power. Canada has the longest coastline in the world.

If Canada remains in NAFTA, the addition of Commonwealth Union membership would also be a great trading advantage. By setting up in Canada, American firms could gain access to the significant British market, as well as those of Australasia. British firms could in the same way gain access to the gigantic American and Mexican markets.

|

| What sets may also rise again. |

Australia has almost the same defense concerns as Canada. It lives in a possibly dangerous neighbourhood, and like Canada lacks the population to defend a vast territory. As an island nation, it needs naval power above all else.

As goes Australia so goes New Zealand--present ties make the two inseparable. At the same time, becoming part of a larger union protects New Zealand from being too dominated by its much bigger neighbour.

There are other potential partners. Ireland, for example. Ireland does not, for historical reasons, want too close an embrace from Britain. But it was vastly to Ireland's economic advantage to be in the EU alongside the UK. Now that the UK is out, Ireland's position is awkward: most of its truck, trade and transit is with Britain, rather than the more distant remainder of Europe. A Commonwealth Union gives Ireland a new and viable option: join the larger group, and the presence of largely catholic Canada and largely Irish Australia prevent English influence from becoming suffocating, as in the EU. Joining the Anglophone union might also make Irish reunification easier: the counterbalancing presence of Britain, Canada, and Australia in the larger union might well make Ulster Protestants feel more secure with Dublin as their capital. Instead of losing their British ties in joining the Republic, they would be broadening them.

The former British colonies of the Caribbean might also make worthy partners. From their point of view, union would boost tourism, often their main income. From the perspective of Canada, and to a lesser extent Britain, they would offer ideal winter tourism and retirement destinations. No doubt there would be some migration of locals to the greener economic pastures of the more developed dominions, but this is not a major consideration pro or con: we are speaking of small populations. Nor are all Caribbean nations poor: the Bahamas, for example, if a member of the union, could pull its own economic weight.

The union might be especially attractive to several Caribbean islands with mixed English and French histories; the strengthening of cultural and tourism ties with Quebec could be alluring. For Quebec, they could be a source of Francophone immigration. More generally, few Caribbean islands are really viable, economically or militarily, as nations by themselves. Joining a larger jurisdiction would be entirely to their advantage.

Singapore would also be on my list. It, too, is too small to protect its own interests, and it is a strategic plum too attractive to any aggressor. Better to form a voluntary union with some larger entity where its concerns are heard, than to sit and quack. This is why, despite ultimately insurmountable demographic difficulties, Singaporeans tried hard to form a union with Malaysia. Association with the Commonwealth Dominions should be more comfortable. Singapore, in return, would be invaluable to the other partners as a regional naval base, and as a regional headquarters to do business with Asia. If Singapore retained its membership in ASEAN at the same time, it would have huge trade advantages, and could offer British, Canadian or Australian firms easy access to the vast and fast-growing Southeast Asian market.

The projected union still, to my mind, with these members, seems relatively lacking in one essential resource—indeed, the most vital. Manpower. Even with these several strong nations linked together, the total population would not be that far north of 100 million—less than a third the population of the US, less than one twelfth the population of China, about the population of Japan. Worse, the demographic trends are toward population decline, barring large immigration from elsewhere. This makes the future, and future prosperity, insecure.

Yet there are obvious risks to large-scale immigration. It can change the culture. This matters: cultures are not equal. The greatest advantage the Anglosphere has, and has always had, is its culture, a culture of public order, respect for law and authority, for individual and property rights, and relative honesty in government. Where and how, then, can the proposed union safely secure its demographic future, without handing away the keys? The more so since the rate of population growth even in the less developed world is beginning to slacken?

|

| Nobody here but us Filipinos. |

India is the obvious solution, but it would be a culturally indigestible chunk. It is many times larger than the rest of the union put together. And Indian culture is, in the end, significantly alien: different languages, very different religion. Moreover, a land power, with other great land powers on its borders—a valuable complementary ally, no doubt, but not a good blend as a full strategic partner.

A better alternative, I propose, is union with the Philippines. Its population, soon to be 100 million, would ensure sufficient manpower for the foreseeble future while being just small enough not to overwhelm. Any Filipino who has graduated high school can speak English, and English is the lingua franca of the country. It is, like the rest of the union, predominantly Christian. It is an archipelago, defensible by a naval power. It is a functioning democracy. While its governmental and legal system are not quite the same as the Commonwealth Realms, they are close relatives: Manila follows the American model, with much current talk of moving towards the Westminster parliamentary system. The Philippines has a strong tradition of seafaring--one in five of the world's sailors today is Filipino. This meshes well with British traditions, and is especially valuable to what would be primarily a sea power and a trading nation. This trading tradition also, not incidentally, makes Filipinos particularly apt at navigating cultural differences and at migration. Wherever they settle, you find no Filipino ghettos. There are not Filipino neighbourhoods the way there are Little Italys or Chinatowns. Give them a generation, and a Filipino family has assimilated.

I expect the Philippines, for their part, would welcome the association. Not just for the obvious economic opportunities for Filipinos, either. When the American Navy pulled out of Subic Bay, there was graffiti reading "Yankee, go home-- and take me with you." Whatever mild thirst there might have been then for going it alone, moreover, has faded a fair bit in the face of new Chinese expansionism in the South China Sea. The Philippines needs to join up with a legitimate naval power.

Britain, Canada, Singapore, and Australia can finance the ships; the Philippines can supply able sailors. The former can offer the capital, the factories, the resources; the Philippines can supply the many willing hands.

Will the pour Filipinos take jobs away from less-skilled Britons or Canadians? Sure. No doubt. But the choice is this: let local and loyal Filipinos take the jobs, or let then be taken by distant Chinese and others. If allied Filipinos take them, the money paid stays and circulates in the union, making the overall opportunities for all of us greater. If we send it to China, the capital and the opportunities are there. And then serve to strengthen an alien system that may be antithetical to our interests.

One more reason that we all might want to do this: one hopes it is temporary, but the US is beginning to look punched out. It seems weary of shouldering alone the burden of being "the world's policeman." Time, perhaps, to call in Scotland Yard. Nations like Britain, Canada, Australia, and the Philippines, who have relied since WWII upon the assured aid of the American military mammoth whenever needed, might be wise to start making alternative arrangements. Indeed, such a strong new partner might persuade the Americans too to stay in the fight. Either way, surely better for our interests than passively ceding the field to some unpredictable other. China? A new caliphate? The BRICS?

The US, in a new wave of its traditional isolationism, also seems to be pulling back from trade deals. The Germans and the French are muttering that the US is not negotiating in good faith on the proposed free trade deal with the EU. But Washington is perhaps only reacting to popular opinion. Americans are sick of the world outside. Both major presidential candidates have announced against the TPP, to which both Canada and Australia were wedded.

This presents for others both a danger and an opportunity. With the US pulling back, the rest of us need new trading partners elsewhere. And it also leaves an opening for someone else to seize the trading opportunities the US is waiving. Another argument for a Commonwealth customs union.

I believe that the union, as proposed, as a free trade area and a unified military entity, would begin life as the third-largest economy in the world, and the third-largest military power. It would only grow in influence and importance from there.

|

Traditional British naval ensign. You know, I see three blank quadrants that might be filled.

|