Monday, April 27, 2015

Sunday, April 26, 2015

The Beatitudes, the Beatified, and the Beautiful

Late have I loved you, O Beauty ever ancient, ever new, late have I loved you!

--St. Augustine

The Beatitudes seem to fairly precisely describe the abused and the depressed as Christianity’s target audience.

So what does this mean in terms of the best “treatment” for depression? What are the implications for the “depressed”?

We have noted that Jesus’s advice to “turn the other check” is actually good practical advice for anyone who finds himself in an abusive situation. But that does not itself deal with the lasting effects of the abuse.

Surely there is more here; for Jesus himself promises it: “Come to me, all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls.”

Sounds good; especially since free-floating anxiety is the most common feature of what is called “depression.”

Obviously, the first thing and the main thing is to embrace Christianity; to, as AA has it, submit to a higher power. This is no small detail. Even those raised Christians, even those who are practicing Christians, may not have really done this in their hearts. There are conversion experiences, and conversion experiences upon conversion experiences. Mount Carmel is a long climb.

But Jesus also seems to suggest something more specific. In his next words, immediately following the Beatitudes, he advises:

13 “You are the salt of the earth, but if salt has lost its taste, how shall its saltiness be restored? It is no longer good for anything except to be thrown out and trampled under people's feet.

14 “You are the light of the world. A city set on a hill cannot be hidden. 15 Nor do people light a lamp and put it under a basket, but on a stand, and it gives light to all in the house. 16 In the same way, let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven.”

This is not just a matter of receiving the sacraments, is it? This is not just a matter of letting Jesus into your heart. These sound much like marching orders.

The most obvious thing is that they are supposed somehow to be noticed: like salt, or light; to be very apparent to the senses. And “good works”: that seems clear enough. We as Christians are supposed to do good deeds: clothe the naked, visit prisoners, feed the hungry, and so forth. The corporal acts of mercy. Check.

But wait. There is a problem here. For, later in the same Sermon on the Mount, Jesus warns expressly against doing such good deeds so that others can see them:

“Beware of practicing your righteousness before other people in order to be seen by them, for then you will have no reward from your Father who is in heaven.”

Accordingly, while we are certainly called upon to do good deeds, and to pray, and to receive the sacraments, this cannot actually be what Jesus is referring to here. Attending church, praying, and the corporal acts of mercy are all supposed to be done in secret. This is no city on a hill, no lamp shining, no salt spreading its taste to the meal. Just the reverse.

Is he referring instead to the “works of the spirit”? The gifts of the spirit are listed variously in different places, but include, according to I Corinthians: wisdom, knowledge, faith, healing, miracles, prophecy, identifying spirits, speaking in tongues, interpreting tongues. They were, most famously, given to the apostles at Pentecost. Jesus does, certainly, in this same passage, compare the depressed to the prophets: “Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you.” That's the most obvious gift of the spirit cited.

Yet it seems this is not meant either. In the same sermon, Jesus warns of false prophets:

“Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep's clothing but inwardly are ravenous wolves. 16 You will recognize them by their fruits. Are grapes gathered from thorn bushes, or figs from thistles? 17 So, every healthy tree bears good fruit, but the diseased tree bears bad fruit. 18 A healthy tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a diseased tree bear good fruit. 19 Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. 20 Thus you will recognize them by their fruits.”If prophets themselves are to be recognized by their fruits, then the visible fruits cannot be the prophecies. That they already manifest, by definition. It seems reasonable too to suppose the same of the other works of the spirit. Indeed, in the sermon itself, Jesus makes clear that non-believers can pull off many of these things as well:

“Many will say to me on that day, 'Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name and in your name drive out demons and in your name perform many miracles?' 23 Then I will tell them plainly, 'I never knew you. Away from me, you evildoers!'”

The visible fruits mentioned--presumably the same thing meant by “shining light,” salt, and “city on a hill”--must be something else.

I doubt many will imagine that the fruits and the works he calls for the dispossessed and poor to do are material riches; perhaps some Calvinists will. But Jesus dismisses this notion smartly enough as well, warning against both riches and, Protestant work ethic to the contrary, working hard and getting ahead.

19 "Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal; 20 but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys and where thieves do not break in and steal. 21For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.

25 "Therefore I say to you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink; nor about your body, what you will put on.Are the “good works” going forth and preaching the gospel, converting and baptizing the nations? One might well suppose so; for later, this is indeed what the apostles are called to do. But this too does not seem right. First, at this early stage in his ministry, Jesus tells his apostles not to do this, but to speak only to the lost of the children of Israel; and he strives to keep his own Messianic identity secret. Jesus also warns in the sermon that "Not everyone who says to me, 'Lord, Lord,' will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven.” So no, it seems that preaching the gospel (i.e., saying "Lord, Lord") is not the fruit either. It is not in itself, although desirable and demanded, “doing the will.”

Jesus also says, in the same sermon, apart from any obvious context, “6 Do not give dogs what is holy, and do not throw your pearls before pigs, lest they trample them underfoot and turn to attack you.” Isn't this actually a warning against preaching the gospel straight up, out in the market place? Note too the echo here of the image of salt being crushed underfoot. In other words, whatever salt is, it is not saying things straight out to anyone who will hear. That is the opposite of salt; that is salt that has lost its savour.

But look again at that passage. Isn't it our key? Isn't it a skillful signal that the entire Sermon on the Mount is a riddle, that the primary point is not being said straight out? It is meant to reveal itself only to those who will ponder it in their hearts.

So what is left, then? The depressed, the abused, are called on to do good works, to let their light shine, to bear good fruit, to do the will of their father. But this does not mean doing good deeds in the common sense. It does not mean prophesying, or performing miracles. It does not mean preaching the gospel. It certainly does not mean getting rich. What is left?

Perhaps it is just my limited imagination. But the only thing that seems to be left is the creation of beauty through artifice—what we might call “art.” The "work" of an artist.

Indeed, if we read the Sermon on the Mount as a riddle, it is itself a good example of the concept. Even if we do not, the saying about casting pearls before swine certainly is; and so is Jesus's characteristic teaching technique, of telling parables. He is an artful storyteller, and storytelling is an art.

So is the image of a “city on a hill,” to which he compares the depressed. A city is an artifice. So is the seasoning of a meal with salt. So is setting a lamp on a stand, and lighting it.

Beauty appears to us through our senses; hence the references to flavour (salt, fruit), light, and the eye. Indeed, what else but the expereince of beauty can Jesus be speaking of in the cryptic phrase:

22 "The lamp of the body is the eye. If therefore your eye is good, your whole body will be full of light. 23But if your eye is bad, your whole body will be full of darkness. If therefore the light that is in you is darkness, how great is that darkness!”

To be able to appreciate and respond to beauty is apparently of the essence. And, while a much larger group is called to be disciples, to be an apostle, one of the twice-called, implies the production of such beauty in some way.

This just makes sense. God, being Supreme Being, is by definition not just perfect goodness, and perfect truth, but also perfect beauty. Just as revering him demands a commitment to truth, and to the moral good, it must also demand a commitment to beauty.

It is in the beauty of the natural universe that we see God.

It is in the beauty of our artifice that we honour him.

\

In this sense we imitate Christ. In this sense we are in the image of God.

Saturday, April 25, 2015

As I Was Saying: How Kids Were Treated Before Christianity

How Christianity invented children:

To be fair, Judaism and Islam are equally guilty of the revolutionary idea of viewing children as human beings.

'via Blog this'

Friday, April 24, 2015

Focus on the Family

|

| The Holy Family - Schiele, 1913. |

We have been taking a few kicks at family values here recently. We have suggested that it--the family--is the source of most of what we call mental illness.

But isn't this supposed to be a Catholic blog? Most people would probably associate Christianity with the phrase “family values.” It is certainly high on the agenda of the current “Christian right” in the US: “Focus on the Family” and all that. In any case, Christian or not, we’re talking Mom and apple pie here. To those who have memories of a loving family, those memories are deeply holy to them, and so too is the ideal of the family.

True. However, as noted previously, the New Testament actually has very little cheery to say about families. Along with the scribes and Pharisees, the family seems to be a special enemy of whatever Jesus stands for. The most Paul can say about coupling off and settling down to that little suburban home behind a white picket fence is “better to marry than to burn.”

And then there is that bit about priests being celibate and all.

What happened to “Honour thy father and thy mother?” Is this a change between the Old and New Testaments? Apparently not. Deuteronomy 13 warns: “If your very own brother, or your son or daughter, or the wife you love, … secretly entices you, saying, ‘Let us go and worship other gods’ …, 8 do not yield to them or listen to them. Show them no pity. Do not spare them or shield them. 9 You must certainly put them to death.”

And is there a single family depicted in the Old Testament that might be held up as a model of a happy and holy home life? Even the families of the patriarchs, God’s own chosen men?

|

| Absalom's death. Dutch. |

Adam and Eve? The eldest son kills the second son. Noah? He curses his third son. Lot? He sleeps with his two daughters. Abraham? He intends to kill one son, abandons the other in the desert. Jacob? He tricks his brother out of his inheritance; but one can hardly blame him, given the extreme favouritism of his father Isaac. Eleven of Jacob's sons conspire to kill the twelfth, Joseph. Moses? An orphan. David? An adulterer who has his rebellious son Absalom killed. Solomon? Kills his brother Adonijah, then takes 1,000 wives and concubines. Some home life these guys had.

It’s all pretty consistent. The great Old Testament prophets, like the apostles of the New, seem to leave family behind: Ezekiel, Jeremiah, Elijah, Jonah, all seem to be unaccompanied by wife or wee ones.

Of course, the point might be that apparently being made in the New Testament, that bad families produce good men, as in the case of the apostles. Unfortunately, however, even the prophets themselves seem to be guilty parties in this: Jacob, Noah, David, Solomon, Abraham, all seem themselves to behave very badly to family members. So the point seems instead that little good is to be expected from families in even the best of circumstances.

Heck, even look at Jesus's own family. They had one child, only one, and they managed to leave him behind in the temple in a strange city, and not notice for a full day.

So how then are we to reconcile this persistent insight with the commandment to “honour our father and our mother”?

First, the commandment is unique in the Decalogue in that it gives a specific reason for itself. This itself implies that the Almighty feels some justification, some explanation, is required. The full passage reads “Honour your father and your mother, that your days may be prolonged in the land which the Lord gives you.” In other words, following this commandment leads to long life.

It is not hard to see why. If each generation looks after their parents in the latter’s old age, they will all live a lot longer. That this is the main point of the commandment would be more obvious in most societies than in modern Canada, with its Social Insurance and Government Health Care. In most times and places, an elderly person who is not cared for by his or her children is dying in the street.

|

| A view from the tragic life story of Old Mother Hubbard. "She went to the bakery to buy him some bread. And when she returned, the poor dog was dead." But probably still edible. |

In the New Testament, Jesus shows the same understanding of the commandment:

Jesus asks the Pharisees, “And why do you break the command of God for the sake of your tradition? 4 For God said, ‘Honor your father and mother’ and ‘Anyone who curses their father or mother is to be put to death.’ 5 But you say that if anyone declares that what might have been used to help their father or mother is ‘devoted to God,’ 6 they are not to ‘honor their father or mother’ with it. Thus you nullify the word of God for the sake of your tradition.” (Mark 15:3-6).

His immediate application of the commandment is to caring for your parents in old age. Jesus adds, as does the Old Testament too, that one must not curse one’s parents. But then again, as Jesus points out in the same sermon, one should not curse anyone. And, as the Book of Sirach points out, the time when one is most likely to revile one's parents, and when it matters, is in their old age:

“O son, help your father in his old age, and do not grieve him as long as he lives. Even if his mind fails, be considerate of him; do not revile him because you are in your prime. (Sirach 3:12-13).

In the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the implications of the commandment are extrapolated into many other realms, but we still find ambiguity towards the family. To begin with, the Catechism insists that this commandment is not binding only on children, but that it “includes and presupposes the duties of parents.” Strictly, this means that if parents do not do their own duty first, their children are not bound.

This makes perfect sense if the commandment refers primarily to the duty to tend to and respect one’s parents in old age. Their own performance of their duties as parents is prior in time, and a prior condition. If they were not good parents to the best of their abilities, they are not owed this.

Why not cite the duties of the parents here as well? Because it is not necessary. Given this need for care in their old age, a parent is in most times and places bound by pure self-interest to treat his or her children well. It is only the latter than need to be reminded of their duty, and called to it by sheer moral force.

Nor would most small children, as a matter of nature, need to be reminded of our duty to “obey our parents.” It is as instinctive as little ducks following their mother. It is not moral behavior. Nor are children yet fully morally responsible. Conversely, at this point, the parents do not need any help in having their will obeyed: they have absolute power.

It is only if we presume the parents are old and powerless that the commandment becomes of some significance.

Nor, at this age, can the commandment require obedience. As the Catechism points out, obedience is not owed a parent as soon as the child reaches maturity or leaves the parental home. This happens, in most times and places, at a quite early age—thirteen, by Jewish tradition. So obedience to parents cannot be the main thrust of the commandment.

What are the duties of parents?

First and foremost, according to the Catechism, even before looking after their children’s physical needs, it is to educate. “The right and the duty of parents to educate their children are primordial and inalienable.” Most important is to educate them in the faith; but next to this, and involved with it, is to educate them in their own chosen vocation.

Parents are expressly prohibited from pushing their children into a particular vocation or profession. They also must not pressure their children into marrying or not marrying any particular person. “Parents should be careful not to exert pressure on their children either in the choice of a profession or in that of a spouse.” Of course, the child’s physical well-being must also be attended to, and parents must not play favourites. That, in the end, is the message of Shakespeare's very Catholic play, King Lear—it is Lear's tragic flaw. (And yes, Shakespeare was a Catholic writer).

|

| Cordelia's Farewll, King Lear; Edwin Abbey |

The Catechism makes clear that the duties of the individual to the family are parallel to the duties of the individual to the state.

Which is, in Biblical terms, damning with faint praise. Render unto Caesar what is Caesar's, certainly; but this also implies that whatever is of Caesar is not of God. The New Testament seems to view governments as intrinsically evil. When Jesus is tempted in the desert, the Devil in person shows him “all the kingdoms of the world,” and says, “I will give you all their authority and splendor; it has been given to me, and I can give it to anyone I want to.7” (Luke 4: 5-6).

So all kingdoms are in Satan’s hands, and he chooses their rulers.

Dig it; that's pretty damning. And so, might the same be so of families?

All else being equal, we should obey the law, for the sake of general peace and order, but “Citizens are obliged in conscience not to follow the directives of civil authorities when they are contrary to the demands of the moral order” (Catechism of the Catholic Church). Similarly in the family, a child is to obey his parents, when in their home and underage, “in all that they ask of him when it is for his good or that of the family.” That is a rather narrow remit. It is just what self-interest alone would require.

If, however, Christianity these days looks very pro-family, it is because the family is under attack. And it is under attack by the state. As we see above, the state is in no way preferable. In fact, by the principle of subsidiarity, it is worse. Salvation comes at the level of the individual, as an independent moral agent. It follows that all decisions should take place at the closest possible level to the individual. What the individual can decide for himself, he should. If any only if he cannot handle something by himself, it devolves to the next smallest possible group, which might well be the family. The larger the group, the farther away from the individual, the farther it is from God and from salvation. This is because the individual has less influence in a larger group.

So family comes before the state.

This must not be twisted into an idolatry of the family.

Friday, April 17, 2015

Jung and the Mandala

|

| Mandala drawn by Jung himself. |

“I gathered all my courage, as though I were about to leap forthwith into hell-fire, and let the thought come. I saw before me the cathedral, the blue sky. God sits on His golden throne, high above the world - and from under the throne an enormous turd falls upon the sparkling new roof, shatters it, and breaks the walls of the cathedral asunder ... I felt an enormous, an indescribable relief. Instead of the expected damnation, grace had come upon me. I wept for happiness and gratitude.” - Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

|

| The real thing: a Tantric Buddhist mandala. |

According to Jung, “it is easy to see how the severe pattern imposed by a circular image of this kind compensates the disorder of the psychic state– namely through the construction of a central point to which everything is related, or by a concentric arrangement of the disordered multiplicity and of contradictory and irreconcilable elements.” Elsewhere, he observes “the mandala is the centre. It is the exponent of all paths. It is the path to the centre, to individuation.”

|

| Church ceiling, Bucharest. |

|

| Church ceiling, Santo Domingo. |

It is also a bit surprising that Jung reached for a Buddhist model in classifying this sort of image, of a variety of things radiating from a central core—for it is at least as common in Christianity. The reason may well be that, had he cited the Christian examples, it would have been too evident to his readers and his patients that he was reinterpreting its significance in a profane way. For in Christian models, and to Christians, it is achingly clear that the subject is the cosmos, not the soul, and that the central point of the motif the divine, is God, not the self.

|

| Rose window, Paris. |

As to Jung's idea that the mandala shows “contradictory and irreconcilable elements,” that too seems debatable, both in its eastern and its western forms. It is, of course, an image of symmetry. Symmetry implies the balance of opposites, as in left and right, up and down. Opposites are not, however, in themselves either contradictory or irreconcilable. Quite the reverse: men and women are opposites, sexually speaking, but in the natural order of things they reconcile rather well. So do left and right. If they did not, there would in fact be no possibility of balance.

|

| Church ceiling, St. Petersburg. |

| Labyrinth, Amiens. A "labyrinth,"in this usage, is the opposite of a maze. There is only one path; one cannot go astray. |

Might it be too unkind to suggest that Jung's interpretation of the mandala is that of a perfect narcissist; the view of an evil man? The self is the centre of everything, and anything that seems good for the self is not just permitted but divinely ordained.

Bad medicine. Although no doubt it played well in the German-speaking world during a certain period...

|

| Labyrinth, Boxgrove. |

Still, I submit that Jung is perfectly right in claiming that the mandala, at least in its proper significance as an image of cosmic order, is indeed an image of mental health. It might even be true that drawing one is a useful form of therapy, as Jung found it.

|

| Rose window, Durham. |

Begin with the premise that mental “illness” generally is mental confusion. This naturally springs most commonly from having been emotionally abused: that is, having been put consistently in a situation in which any conceivable choice is represented as wrong; R.D. Lang's “double-bind.” Take this for a few years, and it gets hard to see which way is up. Take this throughout a childhood, and you are left with very little solid ground on which to grow. Hence the lack of motivation commonly seen in depression: if any move is the wrong move, it is terribly hard to get out of bed in the first place.

|

| Rose window, Strasbourg. |

| Labyrinth, San Francisco. |

Schizophrenia, in which people see or hear hallucinations, may really be no different. As Oliver Sacks points out in his recent book on the subject, hallucinations are in fact fairly common, and in most cases unrelated to schizophrenia. The problem, therefore, may not be with seeing things, but with not being able to meaningfully interpret them, to fit them into one's existing world-view. One therefore becomes confused by them, frightened by them; and this is the “schizophrenia.”

|

| Labyrinth, Lucca. |

This is religion; this is what religion is all about. Religion is the antidote to mental illness. QED.

| Image of New Jerusalem, church ceiling, St. Petersburg. Holy Spirit at centre. |

The mandala is simply the image of this. But icons, as an aid to meditation, can no doubt have healing power. The mandala is an anti-maze, a cosmos in which all the ways have been made straight for the Lord, in which the plain truth is plainly visible.

So religion is the antidote to mental “illness.” Among other things.

|

| Rose window, Chartres. |

This explains Jesus's call to the depressed and abused in the Beatitudes. They are those most in need of true religion.

Jesus even introduces a mandala immediately after calling for their attention. He says, of the abused, "You are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden." (Matthew 5:14). The image of a city is an image of order; being set upon a hill for all to see, and radiating light to all the world—that is a mandala. The city he mentions is, of course, the New Jerusalem, the Christian heaven. At its centre is the Lamb of God, the divine.

|

| The New Jerusalem, French. According to Revelations, it is a perfect cube, symmetrical in three dimensions, made of precious stones, radiating light. |

But the very next thing Jesus says is the opposite of Jung. Jung declares, the heck with conventional morality. You should do what's best for your self. Jesus says conventional morality is not really strong or straight enough; it is a compromise. You should tear out your own eye if it leads you to sin; you should cut off your own hand. You should be perfect, as God is perfect.

| The New Jerusalem. German. |

|

| Labyrinth, St. Lambertus. |

I recall a talk by an Australian priest who, for whatever reason, once had a psychotic break and ended up raving in an asylum. He believes that his cure began—for he is now perfectly well--when a fellow priest came to visit, grabbed him by his shoulders, looked him in the eyes, and, in the true spirit of Aussie mateship, said “You've gone crazy, you bugger.”

|

| Rose window, St. Dunstan's. |

That was the first sane word he had heard since he had been in there. Certainly, he had gotten no truth from the doctors.

Yet it is the Truth that sets you free.

Sunday, April 12, 2015

Not the Onion

Amazingly, this bit of breaking news actually appeared in Salon magazine for Easter.

Jesus went to hell: The Christian history churches would rather not acknowledge - Salon.com:

'via Blog this'

Next, they'll probably reveal the shocking secret that he was Jewish.

Jesus went to hell: The Christian history churches would rather not acknowledge - Salon.com:

'via Blog this'

Next, they'll probably reveal the shocking secret that he was Jewish.

Saturday, April 11, 2015

Let Them Bake Cake

|

| Daniel O'Connell, the Great Emancipator |

Now—this leaves us with a bit of a dilemma. As atheists are the first to insist, atheists can be just as moral as the religious; there is nothing about being religious that automatically makes you more righteous. Yep; agreed. Any properly Catechised Christian could tell you the same. That is just the same as saying that morality is objective, and binding on everyone.

But it follows that there are no special rules that Christians must follow and atheists need not. If it is a moral obligation to turn the other cheek when someone hits you, or to walk two miles when required to walk one, this obligation is equally binding on both atheists and Christians; not on Christians alone.

So the proper question is not whether Christians are or should be doing it in this case, but who is doing it, and who is not. Who here is going to the mattresses in defence of their claims, and who is not?

On that one, you decide.

But let's also dig a little deeper here. I think it is evident to conscience, which is innate, that in ordinary circumstances, neither Christians nor atheists in truth have a moral obligation to “turn the other cheek” when attacked. This goes well beyond the golden rule. Doing unto others as we would have them do unto us does not mean we should subjugate our interests, much less our moral judgements, to theirs, but that we should treat the two equally. The right to self-defence (not to mention freedom of conscience) is inherent and self-evident. We can forgive them, or not, later.

Jesus was not, therefore, laying down a general moral requirement. He was, instead, more or less self-evidently, offering practical advice, or speaking of one particular situation.

It is therefore best to examine the context. To whom was he speaking, and in what situation?

The Sermon on the Mount indeed begins with a precise enumeration of whom it is addressed to: the poor in spirit, those who mourn, the meek, the persecuted, the powerless (Matthew 5:2-11—“the Beatitudes”).

If you are in a situation in which you are oppressed and abused, as here, it is almost certainly futile to fight back. The same considerations apply as in the doctrine of just war: if there is no reasonable chance of winning, one does not resort to arms, because worse harm would only come of it. Jesus makes the same judgement later when he first instructs his disciples to go out and buy swords (Luke 22:36), and then, when he is taken in the Garden of Gethsemane, forbids then to use them (Luke 22:51). Wer have the right of resistance; nevertheless, resistance in some circumstances is futile.

His advice here is plainly for such situations. Saint Augustine points out an interesting detail in Matthew's account. Jesus says, to quote the phrase in full, “if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also.” Why the right cheek specifically?

I challenge you, right now, to try slapping the person nearest to you on their right cheek. I expect that they will escape with little harm.

If, like almost everyone, you are right-handed, you will find it difficult to do. A blow with the right hand will fall on the left cheek. For the right cheek, you will need to slap them with your weak hand. Odd, isn't it?

Unless, that, is, you show your victim, as the idiom goes, the back of your hand. A backhand blow—a deliberate insult. A blow given only by a superior to an inferior.

If not that, the assailant might be attacking backhand with a stick or a whip in his hand.

Now, imagine receiving such a blow, then turning the left cheek to your attacker.

Surely this is a clear example of passive resistance. By turning the other cheek, asking for a straight blow, you are implicitly declaring yourself an equal, in a way that would be awkward for the assailant to respond to. You are shaming him.

|

| St, Francis in later years. |

Jesus goes on to say “if anyone would sue you and take your tunic, let him have your cloak as well.”

In ancient Judea, a poor man would have only two articles of clothing: his tunic, and his cloak. Handing both over would leave him standing naked before his tormentor—making a public scene that would be calculated to shame him. Similarly, when St. Francis's father pursued him to a church, demanding he return his inheritance over his plan to leave the family business, Francis stripped himself naked in front of the bishop, and handed back even his clothes. Touche.

Jesus next advises “if anyone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles.”

Who exactly can force you to go one mile? This seems to be a reference to impressment by the Roman authority. By law, any civilian could be required by any Roman soldier to carry his burden for him for one mile. Simon of Cyrene was so impressed on the road to Calvary. But this was a maximum, not a minimum; soldiers could not require more than this. Accordingly, continuing to carry the burden for an extra mile was actually putting the soldier in violation of the law, perhaps to his peril. Imagine being caught by your superior in this situation, and having to claim that the Jewish civilian insisted on carrying the pack twice as far of his own free will. Right--who was going to believe that?

Jesus's advice is indeed extremely wise, given any situation in which conventional resistance is futile. The early Christians proved the thesis, managing with it to take over a Roman Empire originally bent on their destruction.

Daniel O'Connell, in the first half of the nineteenth century, grasped the same New Testament principle, and used it to force England to give the Irish, and Catholics, political and legal equality throughout the Empire. He had a great deal to do with giving Canada and other colonies self-government as well.

Mohandas Gandhi picked up the same concept of passive resistance in India--without properly crediting O'Connell, but properly crediting Jesus and the Sermon on the Mount. It led to the peaceful independence of India, and probably had a great deal to do with the independence, soon after, of all the European colonial possessions.

Martin Luther King Jr. tried it in the US South, and it worked again to wipe out segregation and discrimination.

But what this doctrine definitely is not is a demand to play dead in the presence of evil. That would simply be cowardice, and completely immoral.

Nor is it called for in the current struggle, involving the various RFR Acts in the US. The religious, after all, still have a vote, and quite possibly majority support. That means they still have conventional means to resist. To start baking extra cakes at their own expense now would therefore only be servile. That would be more like the Uncle Toms, the native Irish converts to Anglicanism, the kapos of the death camps, or the Sanhedrin.

Would such a display of docility attract some to the faith? I doubt it. There would be very little that was attractive about it.

Saturday, April 04, 2015

The Denial of Service to Gays

It is the endemic denial of sexual services.

It has come to our horrified attention that the great majority of men--in fact, by some estimates, ninety-nine percent—actually will, when asked politely, refuse to have sex with gay men; and the same might be said, if it were permissible to criticise women, of most women with regards to their lesbian sisters.

Painful as it doubtless must be to have to phone twice to find a wedding planner, there really is no comparison here. The denial of love—actual love—must have real and almost daily consequences for the average gay. Given that only one percent of men will agree to gay sex--let alone gay marriage—the LBGT choice of love partners is obviously severely constrained, as is their chance at joys and pleasures of life that straight people can simply take for granted.

I hope that those who truly care about human rights and human equality will not rest on their laurels with this current victory in forcing Indiana to blot out previously recognized rights of conscience, but will get right on the far greater problem, and swiftly frame legislation everywhere that will oblige us all not to discriminate in this regard, on religious grounds or for any other spurious and dishonourable reason. Human dignity and human equality demands it; and, after all, freedom of association and freedom of conscience having now been utterly dispensed with in US law, there is nothing any longer to stop us. We have no excuse.

Friday, April 03, 2015

Churchill and Truth

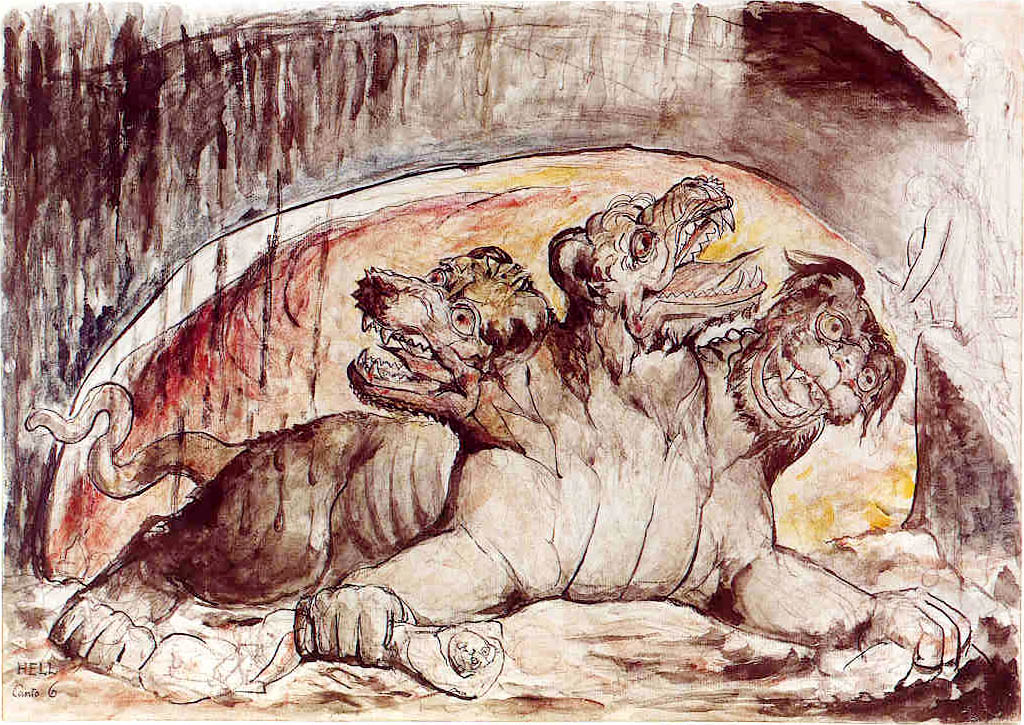

|

| William Blake's vision of Cerberus, the black dog that guards the entrance of Hades. |

Churchill, we know, suffered his entire life from what we now call bipolar disorder type II—depression interspersed with periods of mild euphoria. He himself credited his “black dog” with the insight to see and comprehend the danger of Adolf Hitler, when no one else in authority in Europe did, nor would listen when he did. Later, it allowed him to be the one to first raise the alarm about the postwar Soviet Union and the “iron curtain falling over Europe.” It was, in effect, a gift of prophecy.

William Blake, also a known sufferer from depression, had the same gift. Prophecy, he said, was simply the ability of some men to see with special clarity the forces at work, and therefore to see where they were heading.

It seems that the experience of repeated abuse, and/or the resultant depression, gives some people this ability. It gives them a special spiritual insight. Recent studies show, for example, that the depressed are better than the rest of us at empathy. Nothing occult about this: it is largely a commitment to truth, a question of recognizing true evil or true suffering when you see it (and phony suffering when you see that, too). But it explains why the depressed or melancholic or “mentally ill” were once fully employed by their societies as shamans, or as prophets, and why we might do very well to employ them for this purpose once again.

I have noted in this blog before the near-universal tendency among us to deny the very existence of evil. In the 1930s, nobody wanted to believe for a moment that Hitler was evil. No, poor chap, it must be all a misunderstanding. I'm sure that, if we can just look each other in the eye around the table in Munich, we can work something out. Hitler is a man we can do business with.

The abused at least have been disabused of that pollyanish superstition. They have known evil, and they know it to be real. They can smell it when they again encounter it. They are the natural authorities. They have a special expertise, which a wise society ought to exploit for its own protection. They can predict what it will do next, and they can predict how things are likely to end.

In the same way, having known true suffering, the abused and depressed can recognize it in others. They are less likely to pass by the wounded man on the road, pretending that they did not see. They can also better recognize when suffering is faked, when it is simply a case of the princess and the pea, the squeak of a selfish wheel. A caring society ought to exploit this talent as well.

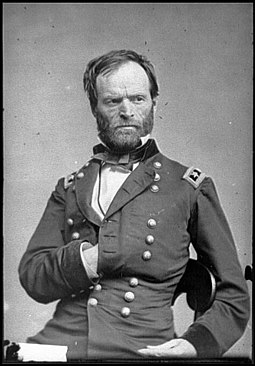

| Keep calm and carry on. |

We can have little doubt from the historical record that Abraham Lincoln also suffered from major depression. He was far from the only person to see the evil of slavery in his day, and far from its strongest opponent. But his experience of depression, and presumably abuse, may have steeled him to the awful necessity of civil war to end it. William Tecumseh Sherman reacted similarly. When the war began, he was struck with a fit of depression that struck others as madness; it may, on the other hand, simply have been a realistic appraisal of what this war would involve. He himself says it was brought on by an understanding of the terrible prospect before him. Because the US was a democracy, in order to end the war, it would no longer be enough, as in European wars of the past, to defeat the opposing army in the field. Any defeat would have to be far more decisive, a destruction of the South's ability to support itself in independence: the first total war. Without this, it would be war without end.

Nobody else saw this; most in the North foresaw a victory by blockade, with little blood shed. Most in the South foresaw a victory by a short display of military valour and determination, convincing the European powers to recognize them. Sherman saw his march through Georgia, burning everything as he went. Sherman was right.

|

| William Tecumseh Sherman. |

The abused and the “depressed” apparently have a more intimate relationship with truth than do the rest of us. The rest of us are usually hiding from truth and from the moral good, imagining or pretending that we are free to believe and do whatever seems convenient for us to believe and do. The depressed and abused, on the other hand, whether this is cause or effect of their abuse, or both, uniquely have the strength to insist on truth, accept the truth, and to act accordingly.

This, I think, fully justifies their special citation by Jesus in the Beatitudes as “the blessed.”

This, I think, fully justifies their special citation by Jesus in the Beatitudes as “the blessed.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)