|

| Moreau: The Lernean Hydra |

As Ovid describes Perseusʼs moment, at his wedding feast, “Phineus and a thousand followers of Phineus, surround the one man. Spears to the right of him, spears to the left of him, fly thicker than winter hail, past his eyes and ears. He sets his back and shoulders against a massive stone column, and protected behind, turns towards the opposing crowd of men, and withstands their threat.”i

Telephus holds off the assembled forces of the Greeks, the same armada that later conquers Troy; he “turned the valiant Danaoi to flight, and drove them into the sterns of their sea-ships,” says Pindar.ii And he rejects the calls of his countrymen to join them in that campaign, continuing to stand apart. Oedipus, if he can be taken as a hero, defeats a force of five mounted men, alone, at the Phokis crossroads.

Jason must defeat an autochthonic army that appears after he sows the dragonʼs teeth: “earthborn men were springing up over all the field; .... And as when abundant snow has fallen on the earth and the storm blasts have dispersed the wintry clouds under the murky night, and all the hosts of the stars appear shining through the gloom; so did those warriors shine springing up above the earth.”iii

Herakles achieves many similar feats. He defeats the Minyans “almost single-handedly.”iv He storms Troy at the head of “only six small craft and scanty forces.”v He holds off the Amazon army, killing each of their leaders. He defeats “hosts of four-legged centaurs.”vi The Lernean Hydraʼs multiple heads seem another image of multitude: “the hydra, that monster with a ring of heads with power to grow again.”vii “Of its fearful heads some severed lay on earth, but many more were budding from its necks,” writes Quintus Smyrnaeus.viii Some say the Hydra had nine heads; some say a hundred.

Being multiple in form seems a standard feature of Herakles’s opponents: “Typhons triple-bodied,” Cerberus, “the three-headed hound, hell’s porter.”ix Geryon has three heads; his watchdog Orthus has two heads. Ladon, guardian of the apples of the Hesperides, is “an immortal dragon with a hundred heads,... which spoke with many and divers sorts of voices.”x

|

| Ravana. |

So too, it seems, with Rama’s great adversary, Ravana: he has ten heads and many arms. Karna conquers a more literal multitude, the entire world, in the name of his friend Duryodhana. Alexander, of course, by tradition, does something rather similar. Moses, less dramatically, must repeatedly struggle against the popular consensus of the Hebrews, who continually turn on him as they wander in the desert. In the end, he does literal battle, and with a small minority of Levites, cuts the majority down (Exodus 32:27-30).

In Hamlet, our hero finds himself alone on a pirate ship, facing the entire crew: “in the grapple I boarded them: on the instant they got clear of our ship; so I alone became their prisoner” (Hamlet, Act 4, Scene 6). But he somehow, miraculously, achieves his freedom. In the more heroic original legend upon which Shakespeare based his play, Amleth holds off the assembled might of England almost alone with a bogus army of the dead.xi Even in King Lear, the abused heroine, Cordelia, is a solitary figure, even her husband absent for the action of the play, while the abusers, Regan and Goneril, are multiple. Lear is stripped of all his retainers but Kent and the fool. Dymphna must face the assembled army of Damon’s kingdom Oriel, with only old Father Gerberus at her side.

Churchill, a modern hero, and a depressive, stood famously against the consensus of his day in resisting Hitler, “a lone voice in the wilderness.”

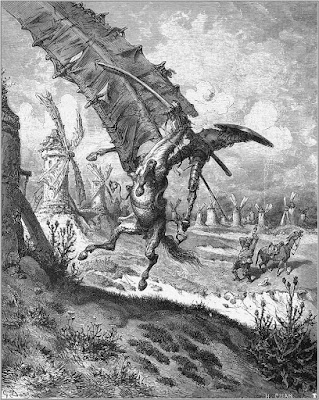

Even Don Quixote, in his quest to be a proper hero, must engage alone against an army of giants:

Just then they came in sight of thirty or forty windmills that rise from that plain. And no sooner did Don Quixote see them that he said to his squire, “Fortune is guiding our affairs better than we ourselves could have wished. Do you see over yonder, friend Sancho, thirty or forty hulking giants? I intend to do battle with them and slay them. With their spoils we shall begin to be rich for this is a righteous war and the removal of so foul a brood from off the face of the earth is a service God will bless.”xii

|

| Don Quixote does battle: Dore |

Many folk heroes are outlaws, who operate in defiance of the government, the social order, of their day: Robin Hood, the 108 Heroes of the Water Margin of Chinese legend, Zorro, the Scarlet Pimpernel.

This motif of one against many seems to reflect a characteristic we have seen in the depressed. Solitude is definitive, Robert Burton suggests, of the spiritual zone the melancholic inhabits. “Above all things they love solitariness.”xiii Diderot too cites “a firm penchant for solitude” as one of the chief features of melancholy.xiv The melancholic is a loner.

The hero type, it would seem, intensifies this characteristic. The merely depressed removes himself from the social whirl. The hero attacks it, rapier drawn.

According to Adult Children of Alcoholics, the second sign that you have been raised in a dysfunctional family is “We became approval seekers and lost our identity in the process.” Number seven is “We get guilt feelings when we stand up for ourselves instead of giving in to others.” Number twelve is “We are dependent personalities who are terrified of abandonment and will do anything to hold on to a relationship in order not to experience painful abandonment feelings.”xv

At first glance, this seems to contradict both conventional wisdom about the melancholic, and the hero legends. It paints the abused child as a compulsive crowd-pleaser.

But it may, instead, point out the reason why the depressed crave solitude, and why the hero stands alone in defiance.

The family is our first society; it is the introduction for each of us to social life, and all social life in microcosm. In the words of the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

The family is the original cell of social life. ... Authority, stability, and a life of relationships within the family constitute the foundations for freedom, security, and fraternity within society. The family is the community in which, from childhood, one can learn moral values, begin to honor God, and make good use of freedom. Family life is an initiation into life in society. (para. 2207).

In the case of an abused child, however, this original society is corrupt: his or her family is “dysfunctional.” It teaches all the wrong lessons. What then?

He must, then, fight against it if he (or she) is ever to grow out of his abused state; just as he must solve the riddle of the double-bind of filial duty. This will require heroic courage: the courage of High Noon. For, as the ACA “Laundry List” suggests, the more spontaneous response is to keep trying harder to seek an approval that will never come. Trapping you in another double-bind.

This illustrates the depth of the challenge faced by the abused depressive; and the degree to which he or she manages to overcome this perhaps marks the division between the ordinary depressed and the heroic. This is indeed what ACA advises in their “recovery” program. Seeking solitude or exile is the first sign of health. Rebelling against the corrupt social consensus is the ultimate victory.

However, this developed ability, if it is ever developed, to think for himself or herself, working only from first principles, would then serve the melancholic well for any enterprise requiring creativity or coming up with novel thoughts; for being a culture hero, an artist, or a leader of any sort; for becoming an explorer, a discoverer. See Burton’s armillary sphere and cross staff, used as personal emblems.

To become a hero, the abused must fight this great battle against the many-headed monster of social consensus, which is poisoning the landscape all about them.

And it is the abused child, specifically, who is called to this by circumstance.

iOvid, Metamorphoses, Book 5, ll.149-199. Mary Innis, trans.

iiPindar, Olympian Odes, 9. Myers trans.

iiiApollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, Book 2, ll. 1340-1407.

ivRobert Graves, The Greek Myths, vol. 2, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, Pelican, 1955, “Erginus,” entry 121.

vGraves, op. cit., “Hesione,” entry 137.

viEuripides, Herakles.

viiEuripides, Herakles.

viiiFall of Troy 6. 212 ff. Way trans.

ixEuripides, Herakles, Coleridge trans.

xApollodorus, Library, 2.5.11 Frazer trans.

xiSaxo Grammaticus, “Amleth, Prince of Denmark,” Gesta Danorum, D.L. Ashliman, trans.

xii Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote, Part 1, Chapter VIII.

xiiiAnatomy of Melancholy, Part 1, Section 3, Memb. 1, Subsect. 2.

xivDiderot, Melancholie, Vol. 10, 1765, pp. 308–311.

xv“The Laundry List: 14 Traits of an Adult Child of an Alcoholic,” ACA.

No comments:

Post a Comment