|

| Mojave woman, 1903 |

Feminism has its own version of the familiar “Noble Savage” myth, that bears some consideration here. And once again, Canadian Indians figure prominently.

In her 1972 book Wonder Woman, Gloria Steinem tells the happy story:

“Once upon a time,” [yes, she really begins like that] “the many cultures of this world were all part of the gynocratic age. Paternity had not yet been discovered, and it was thought ... that women bore fruit like trees—when they were ripe. Childbirth was mysterious. It was vital. And it was envied. Women were worshipped because of it, were considered superior because of it.... Men were on the periphery—an interchangeable body of workers for, and worshippers of, the female center, the principle of life.”

Ah, the halcyon days of primordial innocence. Ah, the days of ripening fruit on every tree. Among other marvellous things, women were given much more freedom and respect. There was perfect peace, justice, and equality. There was of course no private property. Everything was held in common, and shared as needed.

|

| Gloria Steinem, not wearing her bunny costume. |

Then someone, surely not a woman, bit an apple. Writing was invented. Knowledge of good and evil, conventional ethics, came inexorably to pass. And all happiness fled, like a wisp of smoke, like an acetate reel on fire, like waking from a pleasant dream. We learned that we were naked.

“The discovery of paternity, of sexual cause and childbirth effect, was as cataclysmic for society as, say, the discovery of fire or the shattering of the atom. Gradually, the idea of male ownership of children took hold....

“... women gradually lost their freedom, mystery, and superior position. For five thousand years or more, the gynocratic age had flowered in peace and productivity. Slowly, in varying stages and in different parts of the world, the social order was painfully reversed. Women became the underclass, marked by their visible differences.”

|

| Jicarilla girl, 1905 |

It was and is an appealing bedtime story, ringing all the old romantic bells of original innocence, along with furthering a feminist agenda. An unkind observer, mind, might note the suspicious lack of evidence, and the odd coincidence that such female-dominated societies disappeared at the very point –the invention of writing--at which we ought to have seen some solid evidence. Rather like a map which marks, wherever there is undiscovered terrain, “There be dragons here.” They must be here, after all, because we know there must be dragons, and we find them nowhere else.

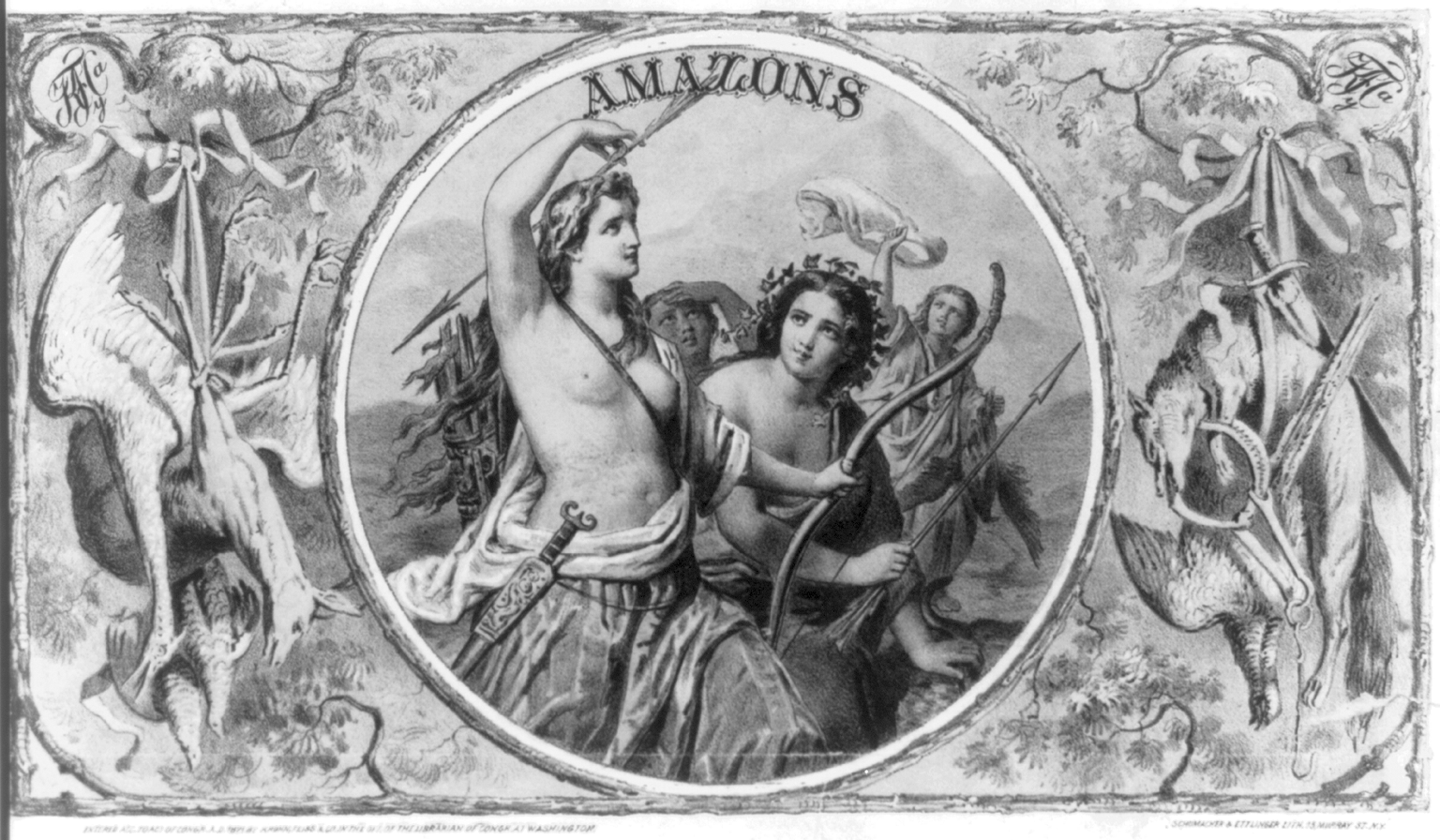

So too, it seems, with Amazons.

One might also think, unworthily, there be here perhaps a wisp of wish-fulfillment. Women were, Steinem suggests, the rightful mistresses of the universe, illegitimately deposed by those dirty, nasty men. Kind of like Scar in The Lion King.

What, then, was Steinem's warrant for this idyllic idea?

The first modern to seriously suggest the existence of a primordial matriarchy was the Swiss classical scholar Johann Bachofen, in 1861. Perhaps a little late for a Romantic. He based his claim of prehistoric “Mother Right” on his interpretation of ancient myth, which he read as history. Astarte, Isis, Ceres as Earth Mother, all that sort of thing.

Never mind that Greek mythology, or Semitic mythology, for that matter, as we know it is pretty male-dominant: Zeus, Kronos, Bull-El, Baal, and the boys. Bachofen detected traces, he believed, of an earlier layer.

It was tantalizing, but all rather speculative, rather debatable. How historic, in the end, is myth? Did Daedalus really fashion workable wings from wax and feathers? Do unicorns really lose their fierceness once resting in a virgin's lap?

|

| Like it says. |

Possibly not. Myths have their meanings, but they may not always be straight reportage.

There was, however, one obvious test. If matriarchy really was the initial and natural order of mankind, some examples should remain today, among more “primitive” people.

Enter, inevitably, on cue, the trusty Canadian Indian. The proverbial, standby primitive for any European uses, and the most available subject of the then-newly-awakening field of anthropology. Of course, the Indians must demonstrate this “Mother Right.” Whether they like it or not.

And, happily, it turned out, on very first appearance, that they did.

The very early and very notable anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan lived in Rochester, New York, right in the old Cayuga country. He therefore based his extensive research on the Iroquois. And, his researches soon showed, the Iroquois were matrilineal. They traced descent in the female, rather than the male, line. This, to contemporary thinkers, was quite a striking fact. It seemed in itself proof positive that the Iroquois, along with the many other Indian tribes that shared this trait, were just such a matriarchy as Bachofen imagined.

|

| Lewis Henry Morgan |

Among those who quickly embraced and advanced this proof of primordial matriarchy were prominent early feminist Matilda Gage, past president of the National Woman Suffrage Association, colleague and collaborator of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She wrote, in her popular book Woman, Church, and State (1893):

“The famous Iroquois Indians, or Six Nations, showed alike in form of government, and in social life, reminiscences of the Matriarchate. The line of descent, feminine, was especially notable in all tribal relations such as the election of Chiefs, and the Council of Matrons, to which all disputed questions were referred for final adjudication. No sale of lands was valid without consent of the squaws ...” (Gage, p. 17-8).

Other than descent from Mom, her claims are not, in fact, supported by what Morgan actually found. It is not possible to trace Gage's references. They are always vague: only the name of an author or, at most, a book, lacking page or edition. But her claim regarding the sale of lands is unlikely on the testimony of Morgan himself, who tells, for example, of the Iroquois defeating the Delaware Indians and “reducing them to the status of women.” The Delaware later sold some of their land to the State, and the Iroquois insisted that this was not permissable, because they were women. Women had no right to buy or sell land.

“'How came you to take upon you to sell land at all?,' the Iroquois chiefs say. 'We conquered you; we made women of you. You know you are women, and can no more sell land than women'” (Morgan, League of the Iroquois, p. 328).

|

| Matilda Gage. But could she waltz? |

As to Gage's “Council of Matrons,” it shows up nowhere in Morgan's study. The closest approach seems to be a comment that “As a general rule the [tribal] council was open to any private individual who desired to address it on a public question. Even the women were allowed to express their wishes and opinions through an orator of their own selection. But the decision was made by the council.” Even the women were allowed to express opinons. There's equality for you (Morgan, Ancient Society, p. 119).

So Morgan, in short, and his evidence on the Iroquois, did not actually support the claim of matriarchy among the Indians. That did not seem to matter: we have already seen the powerful pull of the Noble Savage archetype.

“A form of society existed at an early age known as the Matriarchate or Mother-rule,” Gage asserts enthusiastically, combining Bachofen's thesis with Morgan. “Under the Matriarchate, except as son and inferior, man was not recognized in either of these great institutions, family, state or church. A father and husband as such, had no place either in the social, political or religious scheme; woman was ruler in each. The primal priest on earth, she was also supreme as goddess in heaven. The earliest semblance of the family is traceable to the relationship of mother and child alone” (Gage, p. 13). That sounds pretty definitive. And, as one might expect of the trustworthy Noble Savage, “never was justice more perfect,” Gage assures us, “never civilization higher than under the Matriarchate” (Gage, p. 15). Civilization, it seems, has been going downhill for the last 5,000 years or so.

This matriarchate hypothesis accordingly added another huge hunk of the chattering classes to the lobby for Indian segregation and for preserving or reviving Indian culture. Gage herself was adopted into the Wolf clan, and fought like a Fury against American citizenship for the Iroquois. Whether that was pro- or anti-Indian, you be the judge.

Gage is clearly Steinem's authority on the matriarchate. All Steinem had to do was paraphrase.

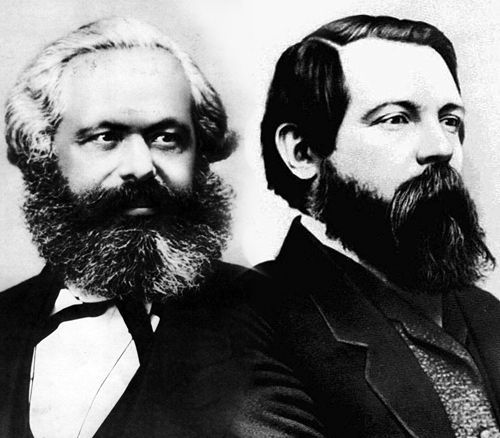

But to fully appreciate the influence of the Iroquois on modern feminism, we must introduce a second authority: Karl Marx.

|

| Not Groucho and Harpo |

He and his co-author of The Communist Manifesto, Friedrich Engels, apparently read Morgan excitedly. It was not just Morgan's research on the Iroquois that enthralled them. Morgan went on to propose a general theory of the development of the family in prehistoric times. In broad outline, it all began, he posited, with group sex, every tribal male “married” to every tribal female. Over time, with the material development of society, this shifted to monogamy. At the same time, tracing descent through the mother was replaced by descent through the father.

This fit perfectly with Marx's own ideas. It was essentially dialectical materialism, extended backwards into prehistory and drawing the institution of the family into its purview. If Morgan was right, he was an important confirmation of Marx. Even better, Morgan had found that Iroquois longhouses held all important property in common. They were, in effect, a working communist society—with all the natural appeal to Marxists that a supposed matriarchy had to feminists.

And so, Engels, in a book-length endorsement of Morgan's ideas, heralded him as one of the great thinkers of the age, one of a scientific trinity with Darwin and Marx (Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State).

It does not seem obviously required by their own purposes for Marx and Engels to concurrently endorse the idea that Iroquois society, and all early society, was also a matriarchy. Nevertheless, they were Germans, and visibly chauvinistically attracted to the writing of their fellow ethnic German, Bachofen. Morgan's theories, after all, did require the notion of original feminine descent. And so, like Gage, Marx and Engels took this as proving matriarchy. Morgan buttressed Marx; and Bachofen buttressed Morgan. Put them all together, and you seem to see the outlines of an irrefutable new science of human history. Inevitable material progress marches on.

Engels therefore concludes, “Communistic housekeeping ... means the supremacy of women in the house ... Among all savages and all barbarians of the lower and middle stages, and partly even of the upper stage, the position of women is not only free, but highly respected…. The communistic household, ...is the material foundation of that supremacy of the women which was general in primitive times” (Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, p. 55).

So now Indians are tied not just to the matriarchy but to to communism, adding another large phalanx of intellectual footsoldiers.

And Engels is right, based on Morgan. Iroquois longhouses were indeed communist. Indeed, Indian reservations are mostly communist today. Nobody owns their house or land. This is, perhaps, one reason for their poverty. Nobody has collateral for a loan, nobody has the incentive to financially strive. But this revelation should not be earth-shattering. All families are naturally communist: from each according to his abilities, to each according to their needs. Indian social order does not progress much beyond the family in any case; tribes are small and interrelated. Any longhouse was essentially an extended family. They were likely to be communistic just as any family is.

But it was all still terribly useful for Marx and Engels. Not only was communism demonstrably doable as a governmental system: it was the natural order of mankind. And, according to Marxist theory, of course, the primordial matriarchy, being communist, must have been free from any exploitation, any social injustice, any war or strife. Making it all look yet more useful to feminists in turn. The two ideologies at this point naturally reinforce.

It also made men, note, the original oppressors, the root of all social evil.

“The overthrow of mother right,” writes Engels, warming to the feminist alliance, “was the world historical defeat of the female sex. The man took command in the home also; the woman was degraded and reduced to servitude; she became the slave of his lust and a mere instrument for the production of children” (Engels, p. 65). The first class distinction was between male and female; the first private property was the wife; and the first oppressive social form was the monogamous family. The family as we know it is the key to all oppression. “The modern family contains in germ not only slavery (servitus) but also serfdom, since from the beginning it is related to agricultural services. It contains in miniature all the contradictions which later extend throughout society and its state” (Engels, p. 66).

One begins to see where modern feminism came from.

“Monogamous marriage,” Engels goes on to explain, “comes on the scene as the subjugation of the one sex by the other, as the proclamation of a conflict between the sexes unknown throughout the whole previous prehistoric period. In an old unpublished manuscript written by Marx and myself in 1846 I find the words: 'The first division of labour is that between man and woman for the propagation of children.'” So children are the problem, the little miscreants. “And today I can add: The first class antagonism that appears in history coincides with the development of the antagonism between man and woman in monogamous marriage, and the first class oppression coincides with that of the female sex by the male” (Engels, p. 75).

So there you have it. Women are the longsuffering proletariat, and men the bloated bourgeoisie.

Feminism as originally conceived had achieved its goals by the 1920s. Women had the vote. Feminism's two most notable secondary goals, prohibition and eugenics, had also by then been gennerally embraced, at least for a time. The fact that neither later turned out well is a separate issue; although that did tend to take the stuffing out of the movement for a generation or two.

|

| The Women's Movement declares victory. 1917. |

Then, in the 1960s, the women's movement booted up all over again. Why? What had changed? What again made it necessary? What were the pressing new goals?

|

| A Friedan slip. |

What devotees call “second wave” feminism was more or less single-handedly kickstarted by Betty Friedan publishing The Feminine Mystique in 1963.

It is probably important to notice that Friedan was a committed Marxist.

She certainly did not reveal this at the time. Then, and ever after, Friedan was adamant that until she researched and wrote that book, she was a typical suburban housewife, with no interests that overreached that station.

This self-representation has since been thoroughly debunked, notably by Daniel Horowitz (Betty Friedan and the Making of the Feminine Mystique). Friedan had for at least the previous quarter century been a committed Stalinist, a frequent writer-–an ideologue, in party terms—for Marxist publications.

Why the deception?

All by itself, it proves how deeply Friedan was influenced by Marx and Engels. She was quoting Engels chapter and verse.

Engels writes “all that this Protestant monogamy achieves, taking the average of the best cases, is a conjugal partnership of leaden boredom, known as 'domestic bliss'” (Engels p. 81).

Friedan begins The Feminine Mystique:

"The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning [that is, a longing] that women suffered in the middle of the 20th century in the United States. Each suburban [house]wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries … she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question — 'Is this all?"

In the climate of the early Sixties, in America, it would not do to make the Marxist provenance plain. The House Committee on Un-American Activities was still in session. Khrushchev had only recently publicly revealed the true depravity of Stalin's rule. If it were too easy to connect these red dots, as Friedan no doubt knew, her project could not have gained popular acceptance. And where would the revolution be then?

Having read Engels, she, a Marxist, obviously saw feminism as an essential element of the class struggle. She was fighting to bring into effect Engels's and Marx's own known agenda. The monogamous family was the foundation of all social oppression. Overthrow the family, and you have the communist utopia.

Or at least group sex, as per Morgan's theories, which might have sounded almost as good to the bored suburban housewife of the fifties.

|

| Maricopa maiden, 1907 |

Or for that matter the repressed Victorian matron of the 1890s. Gage dedicates her 1983 book “to all Christian women and men, of whatever creed or name who, bound by Church or State, have not dared to Think for Themselves.” Christianity, or Christian ethics, is the enemy. Engels also only too obviously turns up his nose at conventional morality, which he calls, ironically for a materialist, “philistine.” And the term “liberated woman,” popular in Friedan's day, had certain connotations associating it with the contemporaneous “sexual revolution.”

For non-Marxists, in particular, this was probably the bait. Buy the concept that women have traditionally been oppressed, and, male or female, you get a blank cheque for unrestricted sex without responsibility.

Along with communism, matriarchy, and equality, this unspoken promise of lots of wild, exciting sex was also projected back on the poor innocent Iroquois. In “Little Big Man,” for example: Dustin Hoffman, as Jack Crabb, adopted by Cheyenne, gets multiple wives. Being Indian becomes a protracted sexual fantasy in Leonard Cohen's 1966 novel Beautiful Losers.

Which is to say, in an odd and funny way, that Canadian Indians are inadvertently responsible for feminism, the New Left, and the sexual revolution.

But enough of that fantasy, for now, and back to the core concept of Indian matriarchy. In the end, how plausible was it?

Significantly, none of this supposed female dominance, or even equality, was visible to early European explorers and missionaries. They tended to report the reverse, and lament the cruelty with which, to their minds, the Indians treated their women. In one of the earliest reports from Acadia, speaking of the Micmac around Port Royal, Father Biard, S.J., writes of “the men having several wives and abandoning them to others, and the women only serving them as slaves, whom they strike and beat unmercifully, and who dare not complain; and after being half killed, if it so please the murderer, they must laugh and caress him” (Jesuit Relations 1, p. 171).

Is this really what matriarchy looks like?

The pale ones also noted that, among Indians, women did all the hard and heavy work, rather like Marx's proletariat, while men lived idly, like Marx's capitalists. “[T]he women ... bear all the burdens and toil of life,” says Father Biard (Jesuit Relations 2, p. 21). “The care of household affairs, and whatever work there may be in the family,” explains Father Jouvency, speaking of the Indians of New France without distinction of tribe, “are placed upon the women. They build and repair the wigwams, carry water and wood, and prepare the food; their duties and position are those of slaves, laborers and beasts of burden” (Jesuit Relations 1, p. 255). Champlain writes that Huron women “have almost the entire care of the house and work; ...The women harvest the corn, house it, prepare it for eating, and attend to household matters. Moreover they are expected to attend their husbands from place to place in the fields, filling the office of pack-mule in carrying the baggage, and to do a thousand other things. All the men do is to hunt for deer and other animals, fish, make their cabins, and go to war” (Champlain, Voyages, p. 319).

|

| Hidatsa madonna and child, 1908 |

This apparent exploitation of the labouring female class ought, one might think, to be a fatal problem for a Marxist. Yet Engels brushes it aside. “The reports of travellers and missionaries,...” he writes, “to the effect that women among savages and barbarians are overburdened with work in no way contradict what has been said. The division of labour between the two sexes is determined by quite other causes than by the position of woman in society.

“Among peoples where the women have to work far harder than we think suitable, there is often much more real respect for women than among our Europeans. The lady of civilization, surrounded by false homage and estranged from all real work, has an infinitely lower social position than the hard working woman of barbarism, who was regarded among her people as a real lady (frowa, Frau — mistress) and who was also such in status” (Engels, p. 56).

So apparently, living off the fruits of another's labour is not, after all, the core issue determining social dominance. It has instead primarily to do with descent being reckoned in the male or female line.

Eh? Surely another example of the tremendous power of the Noble Savage myth.

Again, one sees where Friedan and modern feminists got their shtick. Traditionally, and even more so with postwar labour-saving devices in the home, men do all the dangerous, dirty, and dull work, while women get to spend most of the capital—eighty percent, on average. Yet Friedan and modern feminists saw and see men as dominant, and women as exploited. The traditional deference of men toward women in the West, and all the special advantages they are traditionally given, Engels informs them, are not in their favour, but a tool of their oppression.

|

| Tiwa girl, 1906. |

As to Indians showing no “false homage” towards woman, any thought of chivalry or sentimentality towards the “fairer sex,” Engels is clearly right. Of their frequent bouts of starvation, Father LeJeune writes, regarding the Innu, “When they reach this point, they play, so to speak, at 'save himself who can;' throwing away their bark and baggage, deserting each other, and abandoning all interest in the common welfare, each one strives to find something for himself. Then the children, women, and for that matter all those who cannot hunt, die of cold and hunger” (Relations 7, p. 47). None of this sentimental nonsense about “women and children first.”

Champlain, European bourgeois that he is, is offended, at one point, to find a Huron colleague cutting off the finger of a lady prisoner, to begin the traditional torture. “I interposed,” the French philistine explains, “and reprimanded the chief, Iroquet, representing to him that it was not the act of a warrior, as he declared himself to be, to conduct himself with cruelty towards women, who have no defence but their tears, and that one should treat them with humanity on account of their helplessness and weakness; and I told him that on the contrary this act would be deemed to proceed from a base and brutal courage, and that if he committed any more of these cruelties he would not give me heart to assist them or favor them in the war” (Champlain, Voyages, p. 290).

Sexist pig.

This deference towards women is one of the things modern feminism had to fight hardest against at its inception. This was why “consciousness-raising sessions” were so often required. Friedanites had to convince doubting middle-class women that they were better off not having doors opened for them, not being allowed to pursue whatever interested them at home, punching a time clock, working for a wage by the sweat of their brow, and so on. There was, by comparison, little or no resistance from men, just as there was remarkably little to “first-wave” feminism. By the logic of Sixties feminism, Iroquet was acting rightly, and Champlain was a chauvinist.

Still, one wonders, in the face of actual finger amputation, whether they were right. Our modern society has not yet really put the principle into full practice. If, for example, there were again a general war, with widespread blood and gore and stuff, and there was conscription, would feminists insist that this time, it must apply to men and women equally? Including getting to appear in the crosshairs on the front lines? One wonders. The benefits of femininity suddenly see obvious, to me at least.

But let's assume our consciousness has been raised by the traditional Marxist re-education sessions. Eliminating special privileges for women, and having them do the hard labour, is elevating their status. Fine. As a man, I can live with that. Still, since we were speaking of war, we have another problem with the matriarchy hypothesis as it applies to the Iroquois. As argued by both feminists and Marxists, the existence of a communist, matron-ruled state ought to guarantee general peace. However, on the contrary, the Iroquois cited as the prime example of a matriarchy was one of the most violent and warlike societies known to man.

What? Aren't women then by nature both nurturing and non-competitive?

Gage barely bats an eyelash. “Although the reputation of the Iroquois as warriors appears most prominent in history, we nevertheless find their real principles to have been the true Matriarchal one of peace and industry. Driven from the northern portion of America by vindictive foes, compelled to take up arms in self-protection, yet the more peaceful occupations of hunting and agriculture were continually followed” (Gage, p. 19). So in fact the Iroquois were pacifists, forced against their will to conquer all their vindictive neighbours, torture them to death, exterminate them, their children, and their culture, and confiscate their land. This is proven by the fact that they continued nevertheless to eat.

Procrustes, would that thou wert living at this hour.

There are further problems for this hypothetical matriarchy. One of the strongest structural supports of the thesis from its start is that “primitive people” worshipped “The Goddess.” You've probably heard the claim. “The Goddess” experienced a major revival in the seventies, when Merlin Stone published When God Was a Woman. This book restated the old Bachofen thesis, adding new support from archeology. Or actually, not that much support. Part of Stone's argument was that the physical evidence of matriarchy had been systematically destroyed by later patriarchists. As with most conspiracy theories, the very lack of evidence was taken as evidence. European digs, however, to be fair, were at the time turning up clay figures of a seriously obese woman--obviously, “The Goddess.” From her tiny clay loins, the new subculture of “feminist spirituality” was born. Which form of worship probably involved a liberal use of mirrors.

|

| The Venus of Willendorf. Paleolithic pornography? |

In the celebrated contemporary digs at Catalhoyuk, for example, from 1961 to '65, just when it seemed relevant, such chubby terracotta females did keep turning up. At that particular point, it looked like a lot were; but more recent, more extensive, excavation has yielded a proportion of about 5% of all in-site figurines.

Even if the proportion were much larger, that this demonstrated general worship of “The Goddess” seems a rather thin gruel. There is actually a strong tendeny in many religions, including, to cite a random list, Buddhism, Judaism, Islam and Christianity, to broadly avoid depictions of the supreme godhead in graven form. Anyone who was depicted, or depicted so often, would in fact by that fact have been a lesser personage.

Even in religions that in principle love images, like Catholicism or Hinduism, counting figurines does not seem an accurate theological guide. If, five thousand years from now, one were to excavate a typical Catholic church, one might easily conclude, by the preponderance of statues, that Catholics too worshipped “The Goddess.” Indeed, if one excavated a modern site at random, one might even conclude that modern North Americans worshipped a goddess named “Barbie.”

Moreover, without first buying in to Marxist theory, which was largely what needed to be demonstrated, it is not immediately obvious that the sex assigned to divinity has anything to do with which sex is dominant in society. It helps a lot, in order to hold such a thesis, to already believe in dialectical materialism. You must assume that religion is only a social construct created by the ruling class to serve political ends. A masculine god is therefore there to justify masculine rule, a feminine goddess to justify queenship. Said thesis seems arbitrary. One might argue, instead, even if God is a social construct, that the common Judeo-Christian conception of God as masculine (and assuming, again arbitrarily, that Judeo-Christianity is itself a “patriarchy”) is more a matter of deference to female worshippers. If God is love, and God is a man, who will find God easier and more natural to love, men or women? If God is a man, the soul of the worshipper is symbolically female. So indeed it has been traditionally understood in either the Greek, Jewish, or Christian traditions. Or Hindu, for that matter.

If you walk into a Christian church, you will see many more female than male faces. There is a reason for this.

But never mind all that. There is a certain history here, which must be honoured. To a good Marxist, can Marx and Engels ever be wrong? Surely not; admit that, and the entire mighty edifice of scientific socialism could soon be Ozymandian dust. And Engels, based on Bachofen, wrote, “the position of the goddesses in ... [Greek] mythology, as Marx points out, refers to an earlier period when the position of women was freer and more respected” (p. 71). So the matter is settled. Doubt or further questioning are no longer possible. We must simply move on from here. Gage concurs. Her status among feminists may not be comparable, but perhaps she makes up part of the difference by striving to sound authoritative. “In all the oldest religions, equally with the Semitic cults, the feminine was recognized as a component and superior part of divinity, goddesses holding the supreme place” (p. 16). It must be true; sooner or later the evidence will appear.

But leave aside now our clay figurines and our unimpeachable ideological authorities. Once again, the Indians and especially the Iroquois ought to be our test case. If they are a matriarchy, and if the mythological theory is correct, they ought to still worship “The Goddess.” Do they?

Unfortunately, on present evidence, no. In 1883, working for the Smithsonian, the ethnographer Erminnie Smith made a systematic effort to collect examples of Iroquois mythology. She found them, invariably, insisting that they and their ancestors always worshipped the definitely male “Great Spirit” (Smith, Myths of the Iroquois, 1883, Ch. 1).

Being thoroughly politically incorrect about it, and perhaps hoping otherwise, being herself a woman and influenced by the feminism of the time, Smith hints that nevertheless, oral traditions are not reliable. The beliefs among Iroquois in 1883 may not actually have been their traditional beliefs. They might have been influenced and altered by contact with the larger society.

Fair enough. And so our best source yet again would be the early Jesuits. They were the folks who best knew the Indians at first contact, and they were, naturally, intensely curious about just this, the pre-existing native religious beliefs. It was, after all, their field.

On their evidence, the Iroquois may not have worshipped a Great Spirit. He does not seem to turn up. Their most important divinity may even have been female—the evidence on this seems to go both ways. But if so, she may not have been a figure they wanted to emulate. We do not have much from the Jesuits on Iroquois mythology proper; the Iroquois were at eternal war with the French. Butthey did live long among the Hurons, and the Hurons were, culturally, an Iroquois offshoot. “They say,” reports Jean de Brebeuf, “that a certain woman named Eataentsic is the one who made earth and men.” So there you are: a female creator goddess. “They give her an assistant, one named Jouskeha, whom they declare to be her little son, with whom she governs the world.” So the chief male deity is only her son and assistant. But Brebauf continues, “This Jouskeha has care of the living, and of the things that concern life, and consequently they say that he is good. Eataentsic has care of souls, and, because they believe that she makes men die, they say that she is wicked” (Jesuit Relations 8, p. 115).

So that's a bit of a mixed bag. The creator is a goddess, and the top god seems to be her second banana. On the other hand, she's the devil incarnate. Not quite the moral model one might prefer. The myth does not seem to argue for putting women in power over the local polity.

This seems not to have been the only Huron version of the creation story. There is always something indefinite about oral history. Another Huron informant gave a different tradition to Father LeJeune: “his people believe that a certain Savage had received from Messou [apparently the same as Nanabozho or Nanabush, male, a commonly invoked creator god, or more accurately, the restorer of mankind after a universal flood] the gift of immortality in a little package, with a strict injunction not to open it; while he kept it closed he was immortal, but his wife, being curious and incredulous, wished to see what was inside this present; and having opened it, it all flew away, and since then the Savages have been subject to death“ (Relations 6, p. 157).

This sounds disappointingly similar to the Judeo-Christian tale of Adam and Eve, or the Greek story of Deucalion and Pandora's box. In all three, woman is ultimately responsible for evil. Not an enviable job reference.

|

| Pandora with her box, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti |

A little later, LeJeune also relates of the Indians, “they recognize a Manitou ['spirit'], whom we may call the devil. They regard him as the origin of evil; it is true that they do not attribute great malice to the Manitou, but to his wife, who is a real she-devil. … As to the wife of the Manitou, she is the cause of all the diseases which are in the world. It is she who kills men, otherwise they would not die; she feeds upon their flesh, gnawing them upon the inside, which causes them to become emaciated in their illnesses. She has a robe made of the most beautiful hair of the men and women whom she has killed...” (Relations 6, p. 173).

So female figures may indeed be prominent in Indian and in Iroquois mythology, more prominent than in the Judeo-Christian Bible. But this is not necessarily to women's benefit.

Next, let us turn to the matriarchists' use of their own authorities-- most notably, the field work of Morgan. Of course, Morgan might in turn be wrong. But did he really discover what they said he discovered? Did he actually show Iroquois society to be matriarchal?

Not in any sense that Morgan himself seemed to recognize.

A great deal has been made by later commentators of a note Morgan includes from another source, which puts the case for the ascendancy of Iroquois women about as strongly as can be found anywhere, among those who actually knew the Iroquois first-hand. But this is, literally, a mere footnote. Morgan does not openly disagree with it, but he also does not say that he agrees. It is meant merely to establish that divorce among the Iroquois was easy and frequent, not that the Iroquois were governed by their women.

Here is the relevant note: “The late Rev. A. Wright, for many years a missionary among the Senecas, wrote the author in 1873 on this subject as follows: 'As to their family system, when occupying the old long-houses, it is probable that some one clan predominated, the women taking in husbands, however, from the other clans; and sometimes, for a novelty, some of their sons bringing in their young wives until they felt brave enough to leave their mothers. Usually, the female portion ruled the house, and were doubtless clannish enough about it. The stores were in common; but woe to the luckless husband or lover who was too shiftless to do his share of the providing. No matter how many children, or whatever goods he might have in the house, he might at any time be ordered to pick up his blanket and budge; and after such orders it would not be healthful for him to attempt to disobey. The house would be too hot for him; and, unless saved by the intercession of some aunt or grandmother, he must retreat to his own clan; or, as was often done, go and start a new matrimonial alliance in some other. The women were the great power among the clans, as everywhere else. They did not hesitate, when occasion required, 'to knock off the horns.' as it was technically called, from the head of a chief, and send him back to the ranks of the warriors. The original nomination of the chiefs also always rested with them'" (Morgan, Ancient Society, p. 464).

That sounds at first hearing pretty matriarchal.

| Recreation of a Huron longhouse, Saint Marie among the Hurons, |

Extended families among the Iroquois shared a longhouse. Since the membership in the extended family was decided by female descent, the greatest number of family members would usually be of one clan, the clan dominated by the house's women. But, also interestingly, both Wright and Morgan say this was somehow not always the case. The rule, in other words, seems not to have been: women ruled. It was only that the clan that held a majority ruled, if only through natural clannishness, and this most often happened because of the matriarchal rule of inheritance to be the clan of the majority of the women. In either case, whichever partner was not of the dominant clan was expected to leave the longhouse. Again, it was not a matter of the man having to leave, because he was the man; sometimes it was the woman. Nor was all this such a big deal. Probably nobody had much in the way of personal possessions beyond what they could carry with them, and either had the automatic option of moving to their own clan's longhouse.

The passage also claims one other notable female power. Women, as a group, apparently could overthrow a chief or sachem. Morgan quotes that part without comment; perhaps only because it is extraneous to the point he is trying to make. But it contradicts what he himself observes regarding tribal offices. He says instead that chiefs or sachems were overthrown by council or by popular vote. Council was entirely male, and in popular vote both men and women participated. And women could not themselves serve as sachems or chiefs.

Again, the passage says women could nominate chiefs. But according to Morgan, so, equally, could men; it was done by popular vote without distinction of sex, and in either case selection was subject to the approval of the all-male council.

So all that is established here, even at most, is that women had among the Iroquois a limited franchise: they had voice and vote, but could not be eleced to office. This was somewhat in advance of Canadian or American women's political rights in the days of Matilda Gage; but it does not look terribly impressive by modern standards. Certainly short of a “matriarchy” as Gage or Steinem describe it.

Morgan's own ultimate conclusion on women's status among the Iroquois is rather bluntly stated in his study, League of the Ho-De-No-Sau-Nee or Iroquois (1901): “The Indian regarded woman as the inferior, the dependent, and the servant of man, and from nurture and habit, she actually considered herself to be so” (Morgan, p. 314). Pretty much in line with the early Jesuit missionaries. He further notes the historical position of the Delaware, as previously mentioned, being “reduced” to female status as the result of losing a war. That's “reduced,” not “promoted.” One rarely gets prizes from the victors for losing a war.

“A deputation of Iroquois chiefs went ... into the country of the Delawares, and having assembled the people in council, they degraded them from the rank of even a tributary nation. Having reproved them for their want of faith, they forbade them from ever after going out to war, divested them of all civil powers, and declared that they should henceforth be as women. This degradation they signified in the figurative way of putting upon them the Gd-ka-ahj or skirt of the female, and placing in their hands a corn-pounder, thus showing that their business ever after should be that of women” (League of the Iroquois, p. 328).

Morgan also reports, in passing, the lyrics of one Iroquois war song as: “'I am brave and intrepid. I do not fear death, nor any kind of torture. Those who fear them are cowards. They are less than women'” (League of the Iroquois, p. 259).

Try that in Canada today.

Never mind. Morgan nevertheless clearly showed that Iroquois society was matrilineal: descent was reckoned through the mother. Even with nothing else to grasp at, that was warrant enough, for those who badly wanted to believe, that the Iroquois, and the Indians generally, were matriarchies. It needed to be so. Evidence is so androcentric.

|

| A Seneca (Iroquois) woman. She can run my longhouse any day. |

Engels, indeed, argued that all else necessarily followed from this fact. “the exclusive recognition of the female parent, ... means that the women — the mothers — are held in high respect” (Engels, p. 55). “[T]his original position of the mothers, as the only certain parents of their children, secured for them, and thus for their whole sex, a higher social status than women have ever enjoyed since” (Engels, p. 11).

Gage too considers this standing alone proof that women were dominant. “In a country where she is the head of the family, where she decides the descent and inheritance of her children, both in regard to property and place in society, in such a community, she certainly cannot be the servant of her husband, but at least must be his equal if not in many respects his superior” (note, Gage, p. 14). This must necessarily be so, she argues, not unreasonably, because in the earliest forms of society, the family was the society. If the woman ruled the family, then, she ruled the society, by definition and by default. “Even under those forms of society where woman was undisputed head of the family, its very existence due to her, descent entirely in the female line, we still hear assertion that his must have been the controlling political power,” she scofffs. “But at that early period to which we trace the formation of the family, it was also the political unit” (Gage, p. 15).

Gage's argument omits an important step. Does descent in the female line demonstrate that women ruled the family? Granted, women's clans usually dominated in any given longhouse, and this must have given some real de facto power. But don't women often rule the home in any case? Haven't husbands since time immemorial often been required to smoke on the porch, to not walk on the kitchen floor, to retire to the garage or basement to play with their toys? Descent or inheritance in the female line is rather a passive thing: it does not really mean that any living woman has any particular power over inheritance or descent. Gage, perhaps inadvertently revealing the weakness of her case, further asserts such useful facts as “When an Indian husband brought the products of the chase to the wigwam, his control over it ceased” (Gage, p. 18). But doesn't this simply mean that women did the cooking?

As to Iroquois being matrilineal, that much was surely true. Most Canadian Indian groups were matrilineal, and Morgan found the same arrangement among primitive tribes world-wide. The fact that most Indians traced their descent, like Jesus Christ, through the mother was also clear enough to Champlain and the first missionaries. But the idea never occurred to them, that this was important evidence of female status and control. Rather, they saw it as a simple practical necessity given general Indian promiscuity. In hunter-gatherer tribes generally, there is no effective government, all traditions are oral, and there is little social control. Everyone mostly does what they want. It is hardly surprising if that produces a higher level of sexual promiscuity than in societies with more social regulation—one might say, more civilization. Given little marital fidelity, as a simple matter of practicality, one never really knew who anyone's father was. But one always knew the mother. To keep inheritance in the family line, therefore, and to prevent anyone from feeling cheated or cuckolded, descent had to be traced through the female line alone. And this is just how Morgan, along with Champlain and the Jesuits, understands it. Champlain writes of the Hurons (members, recall, of the Iroquois language and cultural group, even though the sworn enemies of the Six Nations) “when night comes the young women run from one cabin to another, as do also the young men on their part, going where it seems good to them, but always without any violence, referring the whole matter to the pleasure of the woman. Their mates will do likewise to their women-neighbors” (Champlain, Voyages, p. 320). He reports one Indian woman approaching him too after this fashion, but claims he rejected the offer.

|

| Iroquois woman, 1898. She had the vote! |

Generally, according to Champlain, Huron marriage came after the birth of the first child. Taking a husband then became of practical value. Yet even after marriage the favourite game of musical longhouses did not end.

“But while with this husband, she does not cease to give herself free rein, yet remains always at home, keeping up a good appearance” (ibid). Terribly bourgeois of her. It follows, Champlain suggests delicately, that “the children which they have together, born from such a woman, cannot be sure of their legitimacy. Accordingly, in view of this uncertainty, it is their custom that the children never succeed to the property and honors of their fathers, there being doubt, as above indicated, as to their paternity” (ibid.).

The Jesuit Father LeJeune gives the very same explanation--making one suspect that this was the common and quite conscious understanding among the Indians themselves, offered to any European who inquired. “Now, as these people are well aware of this corruption, they prefer to take the children of their sisters as heirs, rather than their own, or than those of their brothers, calling in question the fidelity of their wives, and being unable to doubt that these nephews come from their own blood“ (Father LeJeune, Relations 6, p. 253). It makes sense, even entirely from the male perspective.

This did not, however, apparently indicate either a formal endorsement of free love, or of feminine power. Morgan reports that among the Iroquois he interviewed, albeit a few centuries later, “adultery was punished by whipping; but the punishment was inflicted upon the woman alone, who was supposed to be the only offender.” This whipping was public, before the whole tribe (League of the Iroquois, p. 32).

So much for full sexual equality. And so much for free love. Looks like it can cost something after all.

Among the Sioux, according to Parkman, the punishment for adultery was more severe. Women were physically mutilated. But this, again, applied to women only (Parkman, The Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth Century, p. 17). It seems this practice held not only with the Sioux. Father Savard, in his Histoire du Canada, reports a Frenchman returning from the north shore of Lake Huron with reports of “several girls the end of whose noses had been cut off in accordance with the custom of the country for having made a breach in their honour” (Consul Willshire Butterfield, History of Brule's Discoveries and Explorations, Cleveland, 1898, p. 167).

So Indian family life does not seem to have been quite the paradise of sex on demand and lack of sense of ownership, or indeed of female equality, that the feminists and Marxists might have wished. It was more a matter of there being fewer mechanisms available for establishing misdemeanours or for enforcement. The Mounties just were not yet on the job.

In conclusion, to be strictly fair, despite our mildly mocking at their pretensions, the Marxiststs, feminists, and feminist-Marxists were not altogether wrong. Women in Iroquois and in Indian society did have definite rights, as one assumes women in reality indeed do everywhere, and some of them look fairly significant. They were, at least, not slaves, and any notion among the first European observers that they were seems based in part on cultural chauvinism. The missionaries had to engage in some serious consciousness raising among Algonquin women to convince them of the desirability of monogamy. “Since I have been preaching among them that a man should have only one wife I have not been well received by the women;” writes Father LeJeune, “for, since they are more numerous than the men, if a man can only marry one of them, the others will have to suffer. Therefore this doctrine is not according to their liking" (LeJeune, Jesuit Relations 12, p. 163). All very well for Europeans to observe such fine points of sexual equality. But the constant war among the Indians meant a constant shortage of men, young men being regularly slaughtered in battle. If women could not share husbands, many were not going to have husbands. Fish need their bicycles, after all.

Women also had power, if only de facto rather than based on their sex, over daily activities in the longhouse. They had voice and vote on major appointments and vital tribal decisions. Which is at least more political power than women had in Victorian Canada.

There was a purely practical explanation for their relative power in these matters. It is the same reason that women were left with all the hard work, seen by the first Europeans as proof of their oppression. Aristotle, a fairly astute observer on the whole, even if ultimately a man, noted thousands of years ago, that among the most warlike races, “the citizenry will fall under the domination of their wives.” “This,” he went on to say in his mansplaining way, “was exemplified among the Spartans in the days of their greatness; many things were managed by their women.”

|

| Iroquois women at work |

It stands to reason. If the time and attention of the men are taken up with war, many more matters than otherwise must be left to the women. Something similar happened in the two World Wars of the last century: jobs otherwise held by men were taken over by women, women like Rosie the Riveter, to keep the home fires burning and the troops supplied.

Just so, among the Iroquois, women simply had to be left in charge of the planting and cultivation of crops. Crops grew during campaign season. Without this division of labour, if they ever got planted at all, they would mostly wilt in the fields. Women had to be in charge of the daily routine of the longhouse and family—-just, in fact, as they traditionally are among European Canadians—-because the husband and father would often be away at “work,” and away at work for weeks or months, not just hours, at a time. They would be off on surprise attacks hundreds of miles away, through thick bush, without roads, on foot, in Huron country, or lying in wait for trade canoes somewhere along the St. Lawrence.

The final moral of our little matriarchal parable is this: if Iroquois matriarchy is what you want, it is at least as likely under Hitler's Nazism, with its love of war, as under Stalin's communism. In either case, no need to tackle the daunting and difficult task of reviving traditional Indian culture to do it.

But either way, you may not really like what you get.

No comments:

Post a Comment