|

| Trust me: this Kool-Aid, you don't want to drink. |

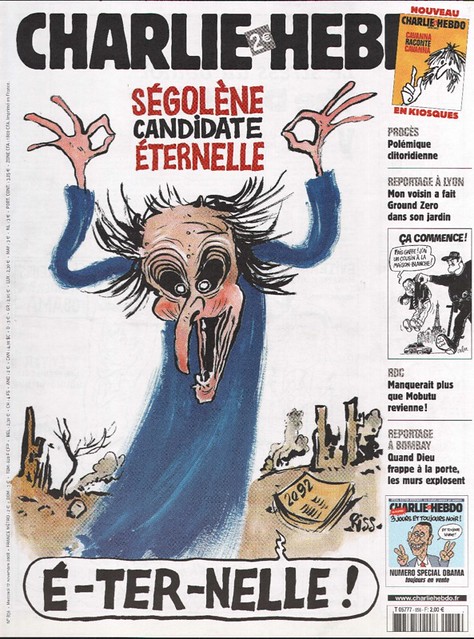

Most of the discussion of the recent

Charlie Hebdo massacre seems to be caught inside a particularly terrible fallacy of the false alternative: either

Charlie Hebdo is in the right, in publishing their satiric cartoons, or the Islamist terrorists were, in shooting them all dead. The Pope's recent remarks, that insulting someone's religion is like insulting someone's mother, ought to have been helpful. But it seems the Vatican had to follow up by patiently explaining that this did not mean he was endorsing murder as the proper response to bad manners.

Is that clear enough? It was pure evil to shoot the cartoonists of

Charlie Hebdo, let lone the random customers of a kosher supermarket. On the other hand,

Charlie Hebdo was and is a disreputalbe publication nobody should want to glorify. I say that even as someone who despises Canada's “hate laws” as an intolerable intrusion on freedom of speech. If the French government, or any government, sought to ban cartoons showing the dangly bits of a prophet who shall not be named, say, or art showing Jesus in a jar of urine, this could probably be justified as a matter of public peace, and could easily be done without infringing on freedom of speech. The matter is parallel to laws against pornography: this too is not a free speech issue. In fact, such things are barriers to freedom of speech, which perhaps are in the public interest to remove.

The classic defense of freedom of speech in its most extreme form is John Stuart Mill's

On Liberty. And he does not shy away from the topic of religion specifically. In fact, he takes it as his example, to show that religious beliefs are not exempt. We cannot know the truth of anything without full presentation of all relevant arguments and evidence. To have all the evidence is most especially important in the case of the most especially important truths, which would be religious truths. Therefore, there must be open and unrestricted religious discussion, without any censorship of anyone's arguments or opinions.

And I agee absolutely with John Stuart Mill. This makes me a radical advocate of freedom of speech, a libertarian on this issue in current political parlance. But note that Mill is speaking of “arguments,” “evidence,” and “opinions.” Pornography, for example, is none of these; no democratic discussion is curtailed, no possible truth is suppressed, no freedom of speech is impeded, if a government passes laws against public indecency. Contrary to common current belief.

Surely simple insults against others' religions or religious opinions fall into a similar category. They are not in themselves arguments, evidence, or opinions. They are just provocations, as the Pope says, like saying "your mother wear army boots."

Unfortunately, Charlie Hebdo seems generally to fall into this latter category. Just provocations; just insults.

Personal insults do not advance a good debate. Instead, they tend to poison the well, so that any real debate gets derailed and forgotten. You might have seen this yourself online: the notorious “flame war” phenomenon. As a result, all the world's parliamentary systems, with the apparent (and perhaps here significant) exception of some in La francophonie, have the established tradition of prohibiting “unparliamentary language,” words one is not permitted to say in a debate. These things are generally personal insults, and they are considered beyond the pale even though the regular laws or libel and slander are suspended.

In Westminster, for example, you cannot call your opponent a blackguard, a coward, a git, a guttersnipe, or a hooligan. You cannot say he is a sod, or slimy, or a wart. In Wales, you may not refer to the Queen as “Mrs. Windsor.” In Dublin, you may not call another honourable member a brat, a buffoon, a corner boy, a scurrilous speaker, or a yahoo. In New Delhi, you must not say he is a bad man, a bandicoot, a goonda, or a rat. In Hong Kong, you must not tell him to “stumble in the street,” or call his speech “foul grass growing out of a foul ditch.” In Ottawa, where we are especially sensitive to such things, you must not call him a parliamentary pugilist, say he is inspired by forty-rod whiskey, that he has come into the world by accident, is a dim-witted saboteur, a trained seal, or "the political sewer pipe from Carleton County." "Fuddle duddle," whatever it means, is also not allowed. In New Zealand, where they are less sensitive, you will nevertheless be ejected from the chamber for calling your worthy opponent's last comment “the idle vapourings of a mind diseased,” noting that “his brains could revolve inside a peanut shell for a thousand years without touching the sides,” or observing that he seems to have “the energy of a tired snail returning home from a funeral.”

It is easy to see, I think, that deliberate insults slung at someone revered by others for religious reasons could and perhaps should be treated in the same way in the public square, and could be prohibited without in any way interfering with honest debate, including debate over the truth of religions. An insult to Mohammed is not a legitimate comment on the teachings of Islam. It is ad hominem, irrelevant, and unworthy of the right honourable member.

It should go without saying that any such law or rule should apply equally in the case of all recognized religions.

Does saying this mean I believe you have the right to kill people who insult you or your religion?

Er, no. I'm also against killings in the House of Commons, actually.

Neither does it justify the hateful Canadian “Hate Laws,” which do indeed criminalize the statement of specific opinions or the mention of well-known facts. Nor does it justify European laws against “Holocaust denial,” and similar matters, like the current mad case that it is illegal in Turkey to say that the killings of Armenians in Turkey in the early 20th century was a genocide, and it is illegal in France to say it wasn't. These laws, by contrast, clearly violate John Stuart Mill's concept of freedom of speech.

But an insult is not an opinion, and established parliamentary practice makes it fairly clear that the distinction can be made consistently.