Women and men are different.

This should not be controversial. It seems to me that anyone

finding this controversial is shockingly lacking in empathy.

Since the Sixties and feminism, we have been fighting against

this truth. Feminism insisted that any difference was just a role forced on

women by society.

Perhaps the rise of the “transgender” movement is at least

in part the inevitable rebellion against this claim. Its insistence on “gender”

as a core of one’s identity is a direct contradiction to feminism. To feminism,

“gender” is not a trait you are born with, but a set of arbitrarily behaviours forced

on you. Otherwise feminism makes no sense.

Transgenders insist there is a female or a male soul. Otherwise

you could not be “trans.”

Leave aside the other questions raised by transgenderism: whether

gender is independent of sex, and whether one can be “born into the wrong body.”

There are three transcendental values: truth, good, and

beauty. They are the goals of existence. They bring value to life. We are created

in order to seek these three things, and to express these three things.

Of these three, it is obvious that women, not men, are most

responsible for beauty. Women are more visually attractive than men; women care

about being attractive; men don’t. This is not just to attract men sexually;

women definitely also dress and make up for other women, for the sake of abstract

beauty. Both men and women would rather look at a woman than a man on a

magazine cover.

If you introduce a woman into a home or office or business,

she will instantly go about trying to make it more beautiful, more comfortable.

You leave men on their own at a workplace, and it will be functional, no more.

Cultures that devalue beauty, like Protestantism, or Islam,

will devalue women. Cultures that value beauty, like France, Italy, or Latin

America, will value women more highly.

This is why feminism began in the Protestant countries. It

was here women were devalued. Although it has since spread to Catholics as well;

due to the overwhelming cultural influence of America.

And why does a man marry a woman? The question has come up

online recently: MGTOW. Is it worth all the insults, demands, and worries, the

risks of ruinous divorce, “just for a vagina”? What else does a woman bring to

the relationship?

This, after all, is what feminism has left us with.

But properly, a man marries to bring beauty into his life. To

make his house a home. Not just her physical beauty, but her charm, her attitude—for

this is her proper role, to be supportive, “inner beauty.” And her ability to

decorate the living space. And her ability to cook, which is a form of beauty, appealing

to the sense of taste. If she is a good wife, she brings grace and comfort to his

life. Along with the joy of children.

This is what a good wife should do. Feminism has devalued it

all, and women have come to neglect and distain all of this. Reducing them to

no more than second-rate men with vaginas.

And now we must acknowledge that men too have their role in

civilization and the human enterprise. As feminism would deny. They are more

than bicycles, more than a means to an end.

Women are the guardians of beauty; men are the guardians of truth.

Men are born with an internal compass that points towards the North Star. Women

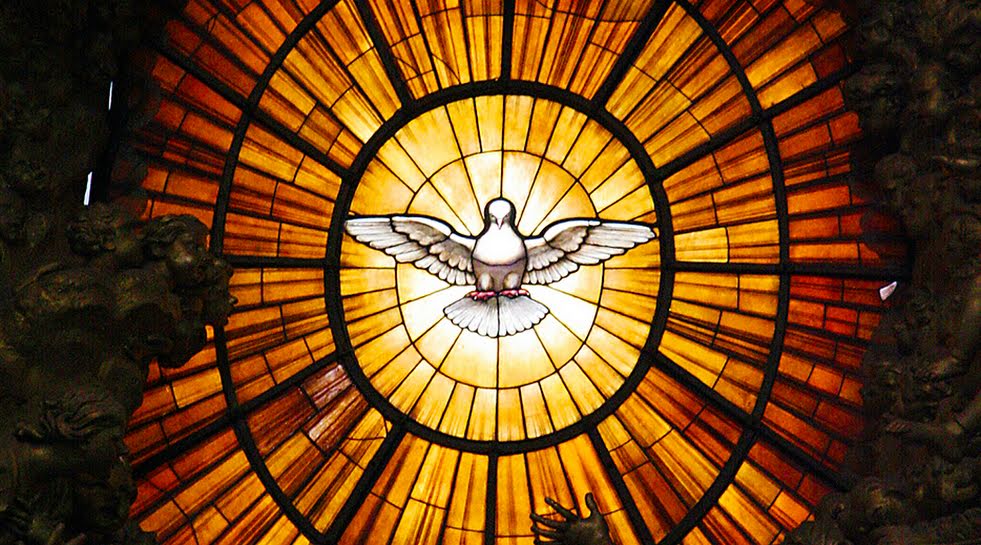

will believe anything; men will want proof. This is why Jesus, who obviously

knew what he was doing, chose only male apostles. We should not second-guess

God. And this is why St. Paul said women should be silent in church. It is not their

role to lead and teach, any more than it is the role of a man to wear makeup and

give fetching smiles. Either has gone off the rails.

Not incidentally, we have made a grave mistake by giving the

teaching profession over almost entirely to women. This is not their role.

Notice that, in the New Testament, Jesus’s genealogy is traced back to David through

Joseph—even though Jospeh is not his biological father. This is because the

role of the father, of he man, is to guide and educate, to pass on truths. In

this sense, Joseph and his genealogy are fully relevant.

If we value truth, but not beauty, as in Protestant (and now

secular) Northern Europe, this will look like a misogynist view. If we value

beauty as well as truth, it will not. It is both received and revealed wisdom.

It is common sense.

And what of the third transcendental value, the good? Indeed,

this is the central of the three: “and the greatest of these is love.” We were

created to choose the good, of our free will.

Men and women seem to have an equal role here; but being

good means different things for each. Goodness means justice, on the one hand;

mercy on the other. In America, to say someone is good, you say “he is honest.”

In China, you say “he is kind.” And these are different things.

Good women are kind and merciful. Good men are honest and just.

We need both. We need both men and women in our culture, and

in our individual lives. And we have lost this.