|

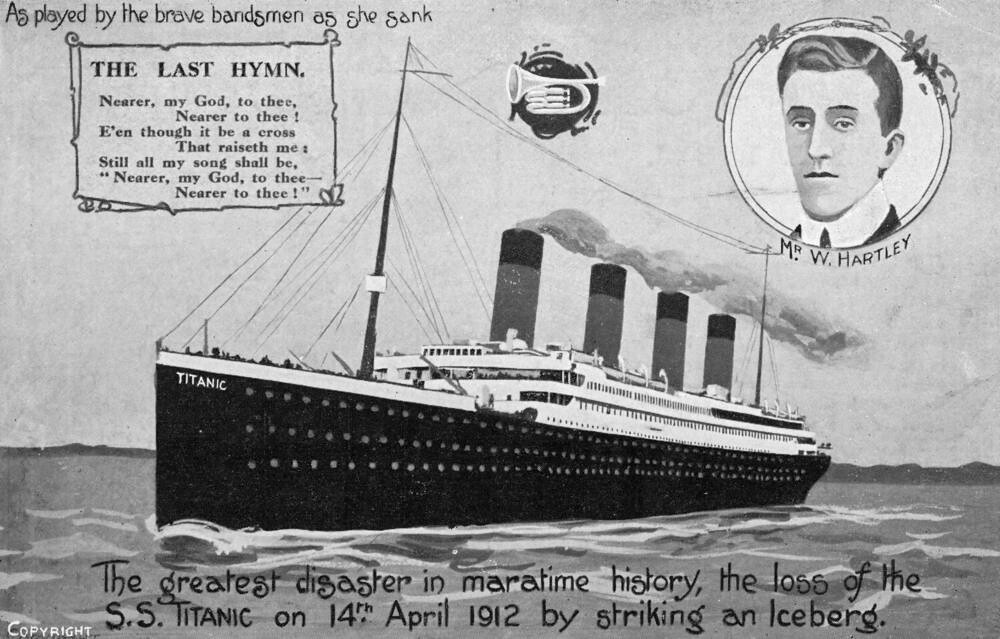

| Pan: Father Nature |

I fell recently into a Zoom discussion on spirituality among avowed atheists. Their challenge was that they found themselves experiencing odd emotions, when, for example, walking through a forest or seeing a sunset. They were discussing among themselves what words to use to express such things. They called it their “spirituality.”

I was fascinated to listen, since I have never knew what people meant by “spirituality” as distinct from “religion.” I do not think they were expecting anyone else at the meeting to be religious, although I think one other participant was. He had a thick accent which I could not place. Otherwise, surely they were being impolite to discuss things in this way, as though religion were out of the question.

One asked, “can there be negative as well as positive spiritual feelings?”

I offered, innocent at this point of their ground rules, “Obviously yes. People speak both of God and the Devil; of heaven and hell.”

This was immediately rejected. “We have to avoid using religious terms.”

“But why?” I asked. “These terms have been established. Why do you need to reinvent it all from scratch? I take it that you do not want to believe in the existence of any metaphysical beings, but then you can understand it all as symbolic.”

“No, no symbols. We can’t allow any symbols.”

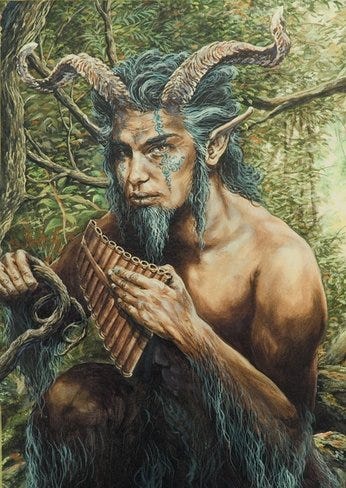

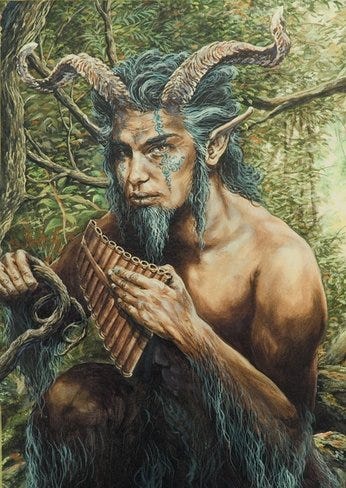

Another participant chimed in soon after, although not immediately after, that panic was a negative spiritual feeling. It came, he noted, from a supposed encounter with the god Pan.

And everyone seemed to accept this.

“Wait,” I inserted. “You broke the rule. Pan is a metaphysical being.”

“No no. I was only using him for explanation.”

My point about symbols exactly. Although I did not pursue it, the problem here was evidently only with the Judeo-Christian God. He who could not even be mentioned. Along with the Devil. Pagan gods were fine. An anthropomorphized and deified Nature or Earth or Ecosystem or Environment was fine.

I asked one participant what their position on religion was more specifically. Why avoid all mention? Did they believe all religion was bunk, or is it that they were not interested, or that they just had not found one that rang true for them--yet?

I got no straight response; only what seemed a deflection. He asked: “How is it that God spoke to us two thousand years ago, then stopped speaking to us; at least, to most people?”

I tried to respond: who thinks God no longer speaks to us? Certainly Pentecostals, Catholics, Mormons, think he still does. But only some of us are listening. The Bible is sufficient for salvation and complete, but that is a different issue. Eternal truth does not change.

At this point another guy cited Dawkins and brought up the problem of evil: “how can you believe in a God who allows children to be born with some genetic defect, then suffer and die young?”

I pointed out that there was thousands of years worth of learned philosophical response to this among the world’s religions; it obviously occurred to everyone. But there was far too much material to go into here in detail. I pointed first to the Christian response: we do not know that physical pain or death is evil. The one thing we know is evil is moral evil; and all moral evil is from man. Eve, meet apple. The sufferings of life, including the physical sufferings, are a result.

Then I cited the Hindu response; the theology of play. Suppose you are playing a baseball game, and the third inning is going very badly. You do not feel good about it. Even so, you win the game, and somehow, you forget the terrible griefs of the third inning, and decide it was actually fun, and you want to play again. Even when you actually lose the game, it is still fun, and you want to play again.

Now suppose you were playing a baseball game in which every pitch was a home run, and you could not lose. Fun? No.

I did not then, but I should have also cited the example of a film or novel. We actually want to see dangers and sorrows. We are not happy with a story in which nothing bad happens.

Pain exists because without it, pleasure would be meaningless to us.

I’m not sure whether anyone got this. It did not seem to provoke a response.

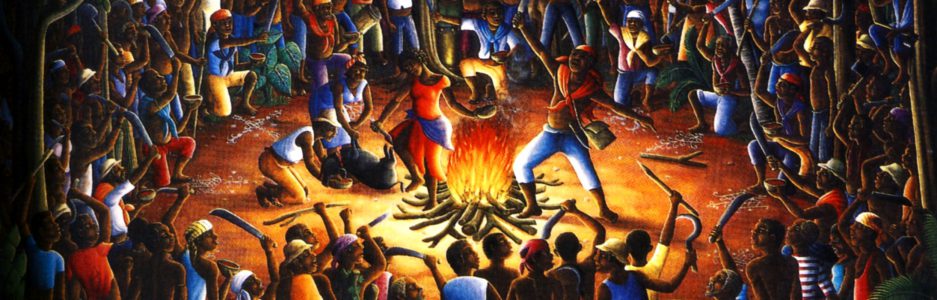

Another guy—I think it was about the problem of evil—started by saying that nature is actually red in tooth and claw, and without this constant strife, we would never have evolved.

And, he concluded, if we all died tomorrow, nature would go on without us. That is the one thing we know for sure.

I’m not sure where he was going with it, but I had to challenge that last statement. It is, at a minimum, not something we know for sure. I suspect it led on to a worship of Nature as some eternal being and ground of the real.

“That is, if you reject Berkeley. And nobody has been able to disprove him.”

“What does Berkeley say?”

“If a tree falls in the forest, and no one hears, did it make a sound? To be is to be perceived by some conscious being. If we did not exist, and God did not exist, nothing else would exist.”

I think that one, too, sailed over their collective heads. It was ignored.

Then someone said something that made me think the real issue was the supposed need to defer to God. The problem was with worship. I cannot recall his words, but that is how I summarized them to him.

Another participant, a woman, spoke up. “If God really is omniscient and omnipotent, and made all things, he should not demand things from us. He doesn’t need anything from us.”

I chipped in: “but what if it is not something he demands, but something he deserves. Do you feel the same way about respecting your parents?”

That seemed to blindside her.

“My parents were terrible.”

“But as a general principle. Not all parents are awful, are they?”

“I can’t answer that unless you define your terms. I don’t know what those words you’re using mean.”

I think I saw here an example of what Scott Adams calls “cognitive dissonance.”

“Which words?”

“God. Parents.”

“I’m using the dictionary definition of parents. I’m using your definition of God. You said it: omniscient, omnipotent, and made all things.”

Someone else said something here in the chat: “That’s a deflection.”

I think they meant the woman I was speaking with, not me.

But the woman I was speaking with disappeared from the Zoom call at this point, without saying goodbye.

I think that means I won my point. I wonder if the topic will come up again next week?

So what have we learned?

I believe there are no atheists. There are only people who do not want to acknowledge any obligations to God or to their fellow man.

_-_James_Tissot.jpg)