It seems to me there is no valid distinction between mind and soul. These are both terms for the perceiving consciousness plus the will. People tend to use “soul” if they are arguing that the mind is immortal.

I hold to this, firstly, by Occam’s Razor: there is no reason

to multiply entities. Secondly, if the soul is not the perceiving consciousness,

the “I,” it does not matter whether it is immortal. And if it is to be judged

based on our acts of will, as all major religions affirm, it must include the

will.

Now, does the perceiving consciousness survive the death of

the body? Is it dependent on the physical brain?

Friend Xerxes write, “no one has ever come back from the

other side to tell us what goes on there.”

This is not obviously true. As Xerxes himself notes, people

have indeed revived after being declared dead; and they have reported experiences

of the hereafter.

Granted, we call them “near-death experiences” rather than “after-life

experiences.”

But there is a tautology here: “brain death” is actually

defined as an “irreversible” loss of brain function. In other words, if anyone

comes back from death, they were by definition not dead.

Are their experiences legitimate evidence for an afterlife?

Xerxes laments, “there is no way of testing the validity of

their memories.”

But there is. Those returning to life have reported hearing and

seeing things during the period when they were supposedly dead; and their accounts

are confirmed by others present. So the consciousness survives the absence of

all activity in the brain, at a minimum. And the claims of out of body

experiences have also been confirmed: they were able to accurately report

things they could not have seen from their body. So the consciousness is not

tied to the body.

We cannot similarly independently confirm their reports of a

world apart from the physical world, to which they journey. But we can confirm

it by the fact that those experiences tend broadly to tally among different

reports. As Xerxes notes: “Often they report seeing bright lights, moving down

some kind of tunnel, being welcomed into a new world of peace and calm.”

It is on the same basis that most of us confirmed the

existence and nature of Timbuctu, in the days before Google maps. The fact that

those who had not actually been there cannot verify reports is immaterial.

Then there is the witness of Jesus. Xerxes laments that,

having been resurrected, he said “not one word about the far side of death.”

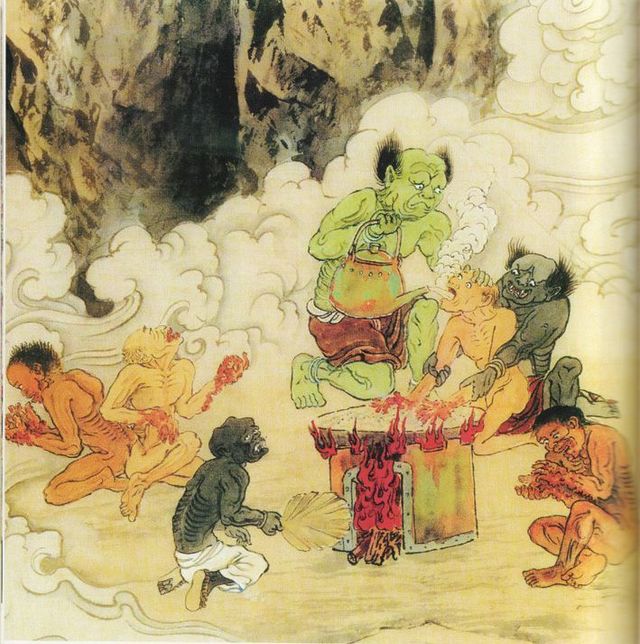

He actually said a lot. This was all that “kingdom of heaven”

stuff. He said after death would come a judgment, and that the good and just

would enter paradise, while the evil and iniquitous would enter eternal flames.

And that there was no passage between the two. More detail is given, albeit not

by Jesus in the flesh, in the Book of Revelations and elsewhere in the Bible.

I imagine Xerxes means Jesus did not say any of this this after

the resurrection. But, having already said it, what would have been the reason

to repeat it now, or for the gospels to record it? Only if, based on his more

recent experiences in the underworld, harrowing hell, his understanding had

somehow changed. Presupposing, as well, that he was not omniscient, was not God,

so that he could have misunderstood previously.

And then, as Xerxes reports from his own experience, there

is the evidence of “ghosts.” People actually seem able to communicate with us, every

now and then, after physical death. While I have not personally had such unambiguous

experiences, many others have, including Xerxes, who has distinctly heard his

deceased wife speak to him in the night, or felt her presence as she rose from

the bed to use the facilities. Such stories are common.

There are other sources of evidence. While anything physical

is transitory, appears and disappears, anything mental or spiritual is

immortal, endures. The cat runs into the bushes and disappears. Yet the memory

of the cat running into the bushes remains in my mind’s eye indefinitely; if it

fades, it can be reinvoked. The mental cat is immortal.

You will say memories fade. But they do not die. We may have

greater or lesser difficulty summoning them to consciousness, as time wears on,

but they are there forever somewhere, and can resurface. A certain smell, a

certain song, the taste of a madeleine…

Try that with the actual cat Sniffles you had as a child.

So it is of the essential nature of the mind to be immortal.

This is not yet to get into the medical reports of those

with virtually no physical brain sometimes nevertheless demonstrating normal

intelligence. This is not to get into the reported miracles of the saints or

Indian yogis, like levitation, bilocation, praeternatural knowledge, and so

forth; which broadly suggest mind can exist and act without dependence on the

physical body. Given, of course, that such reports can be false.

The rational conclusion, therefore, based on the evidence,

is that the mind or soul is immortal; that there is life beyond the life in the

body. It is merely a materialistic prejudice to balk at the idea.

William Blake, or Bishop Berkeley, or Plato, would argue that

the body and the physical world are the epiphenomenon. Only the mind is real. Blake

wrote “the body is that portion of the soul visible to the five senses.”

Berkeley has never been disproven on this. People just don’t

want to hear it.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/1024px-Orestes_Pursued_by_the_Furies_by_William-Adolphe_Bouguereau_(1862)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)