|

"ERECTED BY THE CITIZENS OF GANANOQUE

IN HONOURED MEMORY OF THE MEN OF THE TOWN AND DISTRICT WHO FOUGHT AND FELL IN THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918" |

Often for sport the crewmen will ensnare

Some albatrosses: vast seabirds that sweep

In lax accompaniment through the air

Behind the ship that skims the bitter deep.

No sooner than they dump them on the floors

These skyborn kings, graceless and mortified,

Feel great white wings go down like useless oars

And drag pathetically at either side.

That sky-rider: how gawky now, how meek!

How droll and ugly he who shone on high!

The sailors poke a pipestem in his beak,

Then limp to mock this cripple born to fly.

The poet is so like this prince of clouds

Who haunted storms and sneered at earthly slings;

Now, banished to the ground, to cackling crowds,

He cannot walk beneath the weight of wings.

―Baudelaire

When I was a child, my brother and I used to swap stories about “Wonderfulland,” a place where everything was wonderful. The fact that this was a fascinating topic for us reveals that we were only too aware that, counter to a common myth about childhood, the real word we experienced daily was not so wonderful.

I remember my father describing Belmont Park in Montreal as “the real Wonderfulland,” when he planned to take us there. But I knew in advance this could not be true, and the amusement park, although enjoyable, was nothing like it. Wonderfulland was not a place of thrill rides or cotton candy or custard cones. It was a land of stories where imaginary things were real. One area, as I remember it, was the Old West, one was islands of the Caribbean, one had castles and forests, and so on.

The one detail I remember best is that part of it was Statueland―a garden full of statues.

Why the statues? What did I know of statues? There was, as I recall, only one statue in the small town where I was growing up, of a World War I soldier, commemorating the war dead. It did leave a deep impression on me. We might have seen more statues on a trip to Ottawa; but if so, I cannot remember.

Gananoque, my home town, was also famous for its pink granite. There was a stonemason’s yard on the main street with a display of tombstones.

This, along with the war memorial, seems to me the most likely origin of statueland. It was the land of the dead. Perhaps this is why I have always felt a particular fondness for Remembrance Day.

I rather think that Wonderfulland emerged from our—perhaps only my—intimation that there was a heaven. This might have been instinctive, or rather instilled by God. Or it might have been the result of an early Catholic education.

I thought of Wonderfulland the other night while listening to Bruce Springsteen. I had not thought of it, I imagine, for years. Yet the thought came to my mind, out of nowhere, that this was someone who had visited Wonderfulland. There were hints of it in his music and his voice—not anything explicit, but a mood. It was a mood I knew well, I realized, from other art.

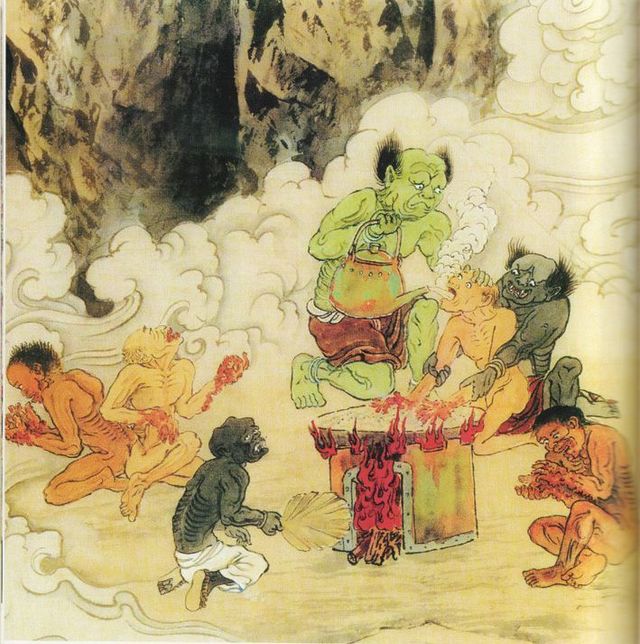

The mark of great art is that it has this sense of Wonderfulland about it. Michelangelo has it; it is all over the Sistine ceiling. Shakespeare often openly refers to it; it is his “green world.” Hans Christian Andersen knows it intimately, and his stories describe it in detail. It is where all fairy tales are set. Romanesque art is the art of Wonderfulland. Chagall paints it. Kurelek paints it. Sendak paints it. Blake paints it, and writes about it. Other writers who clearly know it well include Cervantes; Don Quixote is all about the difference between Wonderfulland and the imperfect diurnal world. Yeats, Stevenson, Coleridge, Hesse, Carroll, Dostoyevsky, H.G. Wells, all write about it. It is where the Krishna Gopala cycle takes place. Arthur Koestler chronicles it in non-fiction.

It is perhaps most present in music. I hear it in Cohen, Dylan, George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Diana Krall, Whitney Houston, Prince, Sinead O’Connor, Ian Tyson, Mark Knopfler, Willie Nelson, Norah Jones, Buffy Sainte-Marie. It is everywhere in classical music. They say all art aspires to the condition of music; they speak of the music of the spheres, and of angels playing harps and blowing trumpets. Perhaps this is why: music among the arts is able most accurately to express the nature of heaven.

“Realistic” art is an absurd and a philistine idea. The purpose of true art is not to show the world, not to “hold the mirror up to nature,” other than to shame it. It is to open a window to a vista of Wonderfulland.

Another insight: those who most experience Wonderfulland are inevitably going to be the most dissatisfied with life here below. The contrast is too intense. At the same time, God seems to give the clearest vision of Wonderfulland to those who are suffering, like Andersen’s Little Match Girl, in this life.

“Socrates: And now, I responded, consider this: If this person who had gotten out of the cave were to go back down again and sit in the same place as before, would he not find in that case, coming suddenly out of the sunlight, that his eyes were filled with darkness?"