|

| A Medieval classroom. |

There is nothing so certainly known, in the world of educational theory, than that lecturing is a lousy idea. “Lecturing doesn't work,” one lecturer affirmed ironically at a conference I recently attended. “We know this. There are so many studies.”

Part of the objection to lecturing is certainly political. It is disrespectful to the learner: it makes the teacher, in the popular phrase, “the sage on the stage,” instead of, as he ought to be, “the guide on the side.” There is an obvious power differential there. Part of the objection is philosophical: all knowledge is now supposedly “socially constructed.” So the instructor has no right to impose “his truth” on the students. We are all supposed to make it up as we go along.

But I note that our present lecturer did object on practical grounds. Here are the practical arguments, as I have heard them:

1) Studies show that we retain very little from what we hear in a lecture.

2) Our attention span is a scant twenty minutes long. Anything after that is wasted breath.

3) We read faster than we can speak. And its all already in the text. It only makes sense to transmit new knowledge by textbook, not lecture.

Class time is better used by having the students work on “projects,” on discussion in groups, or at least some sort of exercise to demonstrate mastery.

Part of the objection to lecturing is certainly political. It is disrespectful to the learner: it makes the teacher, in the popular phrase, “the sage on the stage,” instead of, as he ought to be, “the guide on the side.” There is an obvious power differential there. Part of the objection is philosophical: all knowledge is now supposedly “socially constructed.” So the instructor has no right to impose “his truth” on the students. We are all supposed to make it up as we go along.

But I note that our present lecturer did object on practical grounds. Here are the practical arguments, as I have heard them:

1) Studies show that we retain very little from what we hear in a lecture.

2) Our attention span is a scant twenty minutes long. Anything after that is wasted breath.

3) We read faster than we can speak. And its all already in the text. It only makes sense to transmit new knowledge by textbook, not lecture.

Class time is better used by having the students work on “projects,” on discussion in groups, or at least some sort of exercise to demonstrate mastery.

| Now, siddhus, break into small groups and discuss. |

Nevertheless, I retain my doubts. As a student, this is not at all how it feels. Sitting in that recent conference, I would far rather be lectured to than be told to discuss the matter in groups. First, a project or discussion feels like an imposition: my energies, thoughts and actions are under another's control to a greater extent than if I were passively listening to a lecture. Rather than feeling respected by this, I feel subjugated. Further, I can listen to a lecture and quietly disagree with it, as I did in this case. Being obliged to enter into a discussion or project more or less compels me to agree with whatever has been said or written, or to disagree at the risk of making a scene. Then too, if I am expected to come up with the lesson myself, with reading or with debate, if I am obliged to make all the effort, I begin to question the need for either instructor or class. What am I paying for here? Finally, despite said studies, it really does seem as if time is being wasted, as if it really would be faster and more efficient to just tell us what we are supposed to learn and move on, instead of, too often, frittering time on some project or discussion to demonstrate to ourselves what we already know.

So, how to account for those studies that show lecturing is useless? Well, you aren't likely to hear it in any ed school, but it turns out there are also studies that show the opposite. That's the charm of studies in the social sciences: you can always find one or create one to support any imaginable point of view. The US government sponsored what was probably the largest study of educational techniques ever, Project Follow Through, and it reported back that, at least in terms of results on standardized tests, the technique that worked best was “Direct Instruction,” essentially lecturing to a prepared script. A recent Harvard study suggests the same: that more time spent on lecturing boosts results on standardized tests.

Because in education generally the consumer is given no choice, there is a bias in the industry towards whatever seems in the best interest of the provider. In other words, the idea that lecturing is pointless and the studies that seem to show this have achieved widespread acceptance not so much because they are convincing, but mostly because they are what teachers want to believe. In this regard, there are two problems with lecturing: first, most teachers can't do it well, and second, it is a lot of work.

So, how to account for those studies that show lecturing is useless? Well, you aren't likely to hear it in any ed school, but it turns out there are also studies that show the opposite. That's the charm of studies in the social sciences: you can always find one or create one to support any imaginable point of view. The US government sponsored what was probably the largest study of educational techniques ever, Project Follow Through, and it reported back that, at least in terms of results on standardized tests, the technique that worked best was “Direct Instruction,” essentially lecturing to a prepared script. A recent Harvard study suggests the same: that more time spent on lecturing boosts results on standardized tests.

Because in education generally the consumer is given no choice, there is a bias in the industry towards whatever seems in the best interest of the provider. In other words, the idea that lecturing is pointless and the studies that seem to show this have achieved widespread acceptance not so much because they are convincing, but mostly because they are what teachers want to believe. In this regard, there are two problems with lecturing: first, most teachers can't do it well, and second, it is a lot of work.

|

| Listening to a lecture in the Chautauqua auditorium. |

Most people are not blessed with the ability to give a really interesting talk. It is a talent, like being able to tell a joke, or to write well. Since teachers are not selected for this talent, it is a statistical dead cinch that most teachers cannot pull it off. Most teachers do not want to lose their jobs. Ergo, it is best to believe it is not important.

The obvious flaw in the studies that show learners retain nothing from lectures, and that nobody listens after the first twenty minutes, is that they make no attempt to differentiate between good lectures and bad lectures. All they are demonstrating is that most professional teachers cannot lecture to save their lives.

Consider this: if our attention spans are really only twenty minutes long, how is it that we are all prepared to pay for movies that last an hour and a half or even two hours? A free market should have long ago replaced this with a more profitable format of a series of twenty-minute short features—the more so since, until relatively recently, presenting a longer feature was a technological nightmare, projection reels being only twenty minutes long. How is it that tent revival meetings last days? How is it that the old Chautauqua lectures, which people paid to attend as popular entertainment, sometimes lasted for hours?

The difference is obvious: movies, and good lectures, make some effort to hold our attention. Modern educational doctrine completely ignores the issue of motivation. There is a reason for this: making motivation important puts an onus on the teacher to be interesting. It is better for the teacher if all responsibility is on the students. Twenty minutes is no doubt the limit for fixing ones concentration by sheer will power on something in which one has no intrinsic interest; but this figure obviously varies with interest.

As to reading being more efficient than listening, to believe this requires the second great omission from modern educational theory: memorization. Modern ed theory of course knows about memorization, but it is a bad word, something to be avoided. It is a lower level skill. Accordingly, no notice is to be taken of what is and is not memorable

.

Yet, put simply, if we do not remember, we have not learned.

|

| Prof. Russell Conwell. His "Acres of Diamonds" lecture, the most popular ever on the Chautauqua circuit, runs one hour and twenty minutes on YouTube. |

Yet, put simply, if we do not remember, we have not learned.

The slightest awareness of mnemonics makes clear why lecturing would be valuable even though it it repeats information in the text. It is not just a matter of repetition; we retain exponentially better when more than one sense is involved. Here sight is reinforced by hearing.

The real reason memorization is currently rejected, I suspect, is that it is boring for the teacher to repeat things he or she already knows. It does not follow, however, that this is boring for the student, who does not already know the information. And again, the concentration on “higher level” thinking skills, instead of humble things like memorization, tends in practice to be an intrusion on the student's intellectual autonomy. He or she should retain the right to make his own judgements.

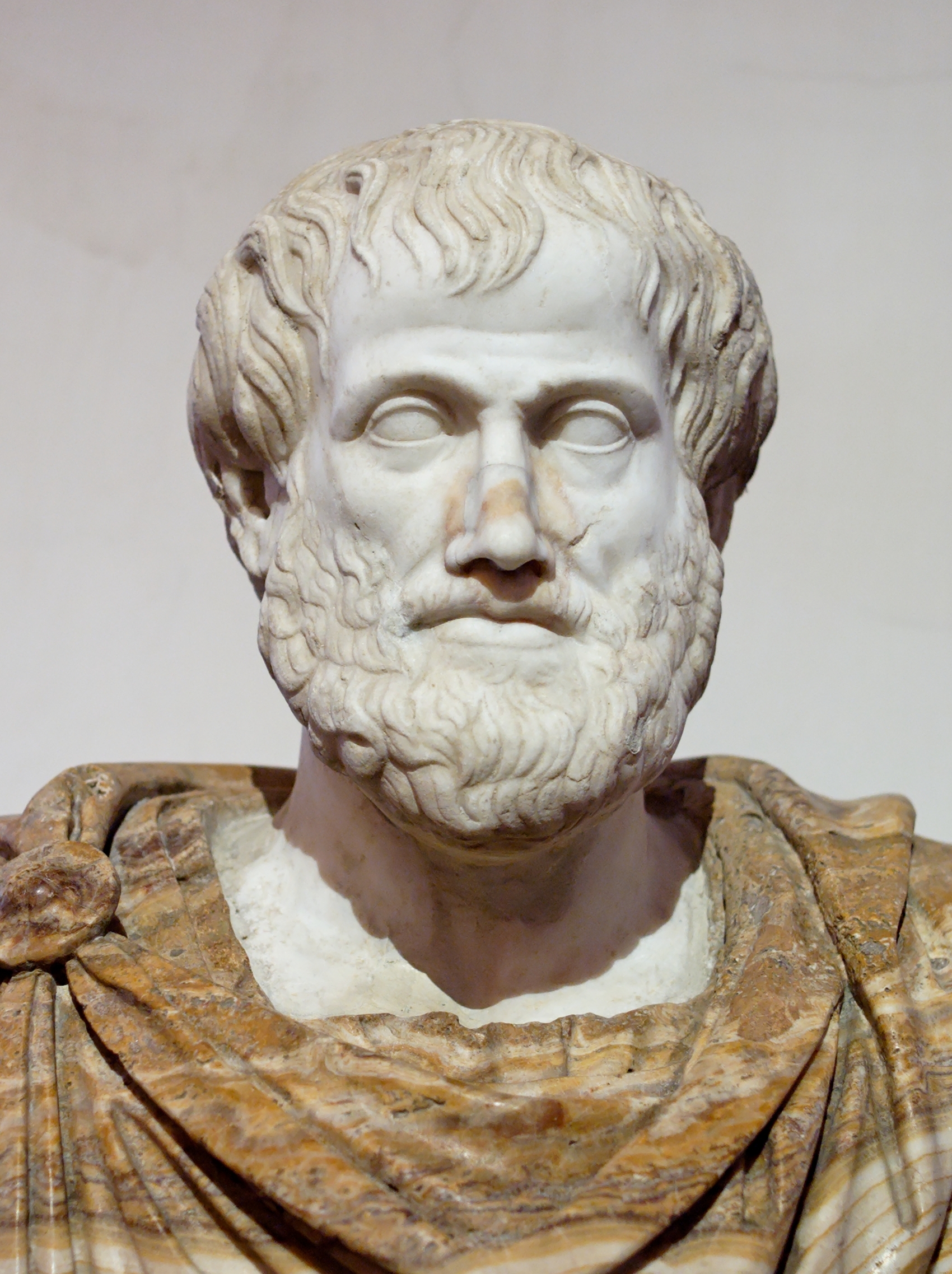

So let's hear it for the good old college lecture. Rejecting the lecture format, after all, requires us to reject the wisdom of the ages, to reject a technique sworn to by many of the greatest minds that ever lived. For most of our greatest minds have been teachers, and our traditional teaching techniques come down to us from them: Aristotle, Plato, Confucius, Mencius, Hillel, Maimonides, Jesus, Aquinas, Gautama, Ngarjuna, to name a few. Cheeky to suppose they all had it wrong.

The real reason memorization is currently rejected, I suspect, is that it is boring for the teacher to repeat things he or she already knows. It does not follow, however, that this is boring for the student, who does not already know the information. And again, the concentration on “higher level” thinking skills, instead of humble things like memorization, tends in practice to be an intrusion on the student's intellectual autonomy. He or she should retain the right to make his own judgements.

So let's hear it for the good old college lecture. Rejecting the lecture format, after all, requires us to reject the wisdom of the ages, to reject a technique sworn to by many of the greatest minds that ever lived. For most of our greatest minds have been teachers, and our traditional teaching techniques come down to us from them: Aristotle, Plato, Confucius, Mencius, Hillel, Maimonides, Jesus, Aquinas, Gautama, Ngarjuna, to name a few. Cheeky to suppose they all had it wrong.

|

| Aristotle. All his surviving writings are actually lecture notes taken by his students. |

Indeed, the quality of a teacher used to be measured directly by his ability to command audiences at a public lecture, and to convince attendees in public debate. There was and is a great deal of wisdom in that. And, whether the educational establishment likes it or not, that is almost certainly where we are headed again. With the internet, learners are now able to seek out and learn from the best lecturers wherever they are. They are no longer stuck with the teacher their school says they must have. Consumer choice is back.

It is a democratic revolution as great as or greater than the printing press.

No comments:

Post a Comment