|

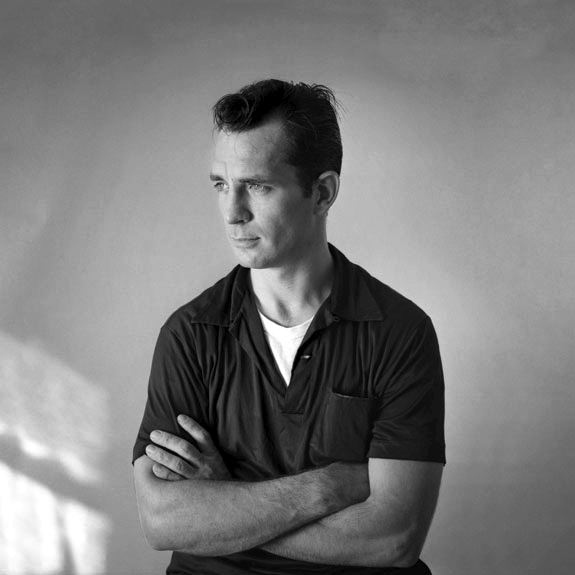

| Kerouac was always an avowed Catholic. So was Andy Warhol. |

Years ago they ... said I was a prophet. I used to say, "No I'm not a prophet" they say "Yes you are, you're a prophet." I said, "No it's not me." They used to say "You sure are a prophet." They used to convince me I was a prophet. Now I come out and say Jesus Christ is the answer. They say, "Bob Dylan's no prophet." They just can't handle it. – Bob Dylan, 1980.

The end of the Sixties almost became a religious revival. It should have. That was where it was all leading. It was a sudden surge of new hope, triggered by victory for the good guys in the Second World War, the biggest wave of new hope since the Waste Land began with World War I. It might have led to something substantial. Instead, some of us dropped dead, and the rest of us sold out.

You might even remember a moment when it looked as though something else might happen. You might remember the “Jesus Freaks,” the Hare Krishnas, the Moonies, and all the terror about cults, in around the Seventies. That could have been the future. Instead, all but a few chickened out. Drugs, sex, and rock and roll, okay, that the broader society could tolerate. But religion? Please. Be spiritual, okay; buy a few crystals. Listen to Enya. Try some TM. But keep those conventional moralities away from our stash. We’ll take meaninglessness any day.

We were speaking a little back about the Byrds. The Byrds definitively broke up during the recording sessions for their 1967 album The Notorious Byrd Brothers. Michael Clarke left in dissatisfaction, supposedly, with the music being written by the band’s composers. David Crosby left or was fired due to a disagreement over whether to include his song "Triad" or the song "Goin’ Back" on the album.

Hmmm. Let’s parse that. You may recall that, beginning at about this time. Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman were tentatively rediscovering Christianity. Clarke and Crosby were both on a trajectory that ended with the utter destruction of their livers. I think we can assume that their world views were beginning to pull apart, and this was merely manifested in their song choices.

Clarke was most likely to be upset over one song, “Artificial Energy.” He had scored a rare co-writing credit on it. The title, and therefore the song, seems to have originally been his idea. But it was completed by Hillman and McGuinn. I suspect they altered Clarke’s original concept. The song begins as a description of the experience of being high on amphetamine—which, of course, sounds like a lot of fun. It ends differently: with the lines “I've got a strange feeling,/ I'm going to die before my time/I'm coming down off amphetamine/And I'm in jail 'cause I killed a queen,” and then a note of musical dissonance. Clarke may have seen this as uncool, and a kind of sabotage. McGuinn and Hillman may have sounded as though they were scolding him. Damned self-righteous Bible thumpers.

As for Crosby, he had written the song, “Triad,” and he badly wanted it on the album. It was a celebration of the idea of a ménage a trois. Hillman and McGuinn voted it down in favour of a song written, insultingly enough, by a third party, “Goin’ Ba ck.” This song, interestingly, could not have been more different in tone than “Triad.” It was a call for a return to the innocence of childhood. “I think I’m goin’ back/To the things I learned so well in my youth…” "Triad"’s lyrics include: “Your mother's ghost stands at your shoulder/Got a face like ice just a little bit colder/Saying to you/

Cannot do that it breaks all the rules/You learned in schools.”

It looks as though the lyrics of “Goin' Back” were a direct response to Crosby. McGuinn and Hillman were perhaps personally repelled by “Triad.” Crosby, for his part, perhaps saw them turning the group into something smarmy and definitely uncool. What was this, Sesame Street?

And then there is a yet more famous breakup: the Beatles. They released their last single in 1970. But what was it? McCartney’s “Let It Be.” The song is obviously religious in tone; it is a prayer to the Virgin Mary. Although McCartney will not say (or deny) it, the title is a paraphrase of Mary’s own words in the Bible. “Let it be done according to thy word.” Paul was raised a good Catholic lad.

That, and some other songs Paul was coming up with at the time that sounded religious in tone—“Blackbird,” “Long and Winding Road”—seem to have been too much for John Lennon's atheist sensibilities. They stopped writing together. On the album version, Lennon introduces “Let It Be” in a comic falsetto voice as “Hark, The Angels Come.” In another take, preserved on the album Anthology 3, Lennon is heard asking in the background, “Are we supposed to giggle in the solo?”

It does not sound as if he was comfortable with the tone of the song.

At the same time, of course, George Harrison was composing religious songs like “My Sweet Lord.” Most of which were not allowed on Beatles albums, and surfaced immediately after their breakup (1970). But he was still on comparatively safe ground, since his stuff sounded Hindu, and was not associated in Lennon’s or the popular mind with any particular morality.

So, leaving Harrison more or less aside, Lennon and McCartney seem to have split at least in part on differing religious outlooks. Lennon went on within a year to record his manifesto “Imagine,” which speaks out directly against religion in its opening lyrics: Imagine there's no heaven/It's easy if you try/No hell below us/Above us only sky.”

It is odd that this pretty obvious religious context has not before been stated outright, either by those involved or by the music critics and biographers. It is as though everyone wants to avert their eyes from any consideration of religion. God forbid—er, let me rephrase that…

I think everyone sensed the danger. When Sonny and Cher had merely come out against drugs in the mid-Sixties, it had almost ended their career. When Paul Revere and the Raiders did, it did.

It was Bob Dylan, in the late Seventies, who finally had the nerve to break the taboo and speak openly. Surely, if anyone was big enough and cool enough to get away with it, it was Dylan.

Big mistake. All hell broke loose.

The fan base spoke of Dylan as though he were some kind of traitor. Dylan himself eventually knuckled to the pressure, and stopped showing his faith, although there is evidence he has never wavered in it personally. And everybody else got the message and pulled in their necks. Many indeed became good Christians privately, but they kept quiet about it, and the popular culture mainstream moved on.

Which might explain the exploding popularity, from about that time, of country music. It was the one place in pop culture where the religious could speak openly and freely. The Byrds and Dylan led the way.

No comments:

Post a Comment