Recessional

God of our fathers, known of old,

Lord of our far-flung battle-line,

Beneath whose awful Hand we hold

Dominion over palm and pine—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

The tumult and the shouting dies;

The Captains and the Kings depart:

Still stands Thine ancient sacrifice,

An humble and a contrite heart.

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

Far-called, our navies melt away;

On dune and headland sinks the fire:

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

Judge of the Nations, spare us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

If, drunk with sight of power, we loose

Wild tongues that have not Thee in awe,

Such boastings as the Gentiles use,

Or lesser breeds without the Law—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

For heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding, calls not Thee to guard,

For frantic boast and foolish word—

Thy mercy on Thy People, Lord!

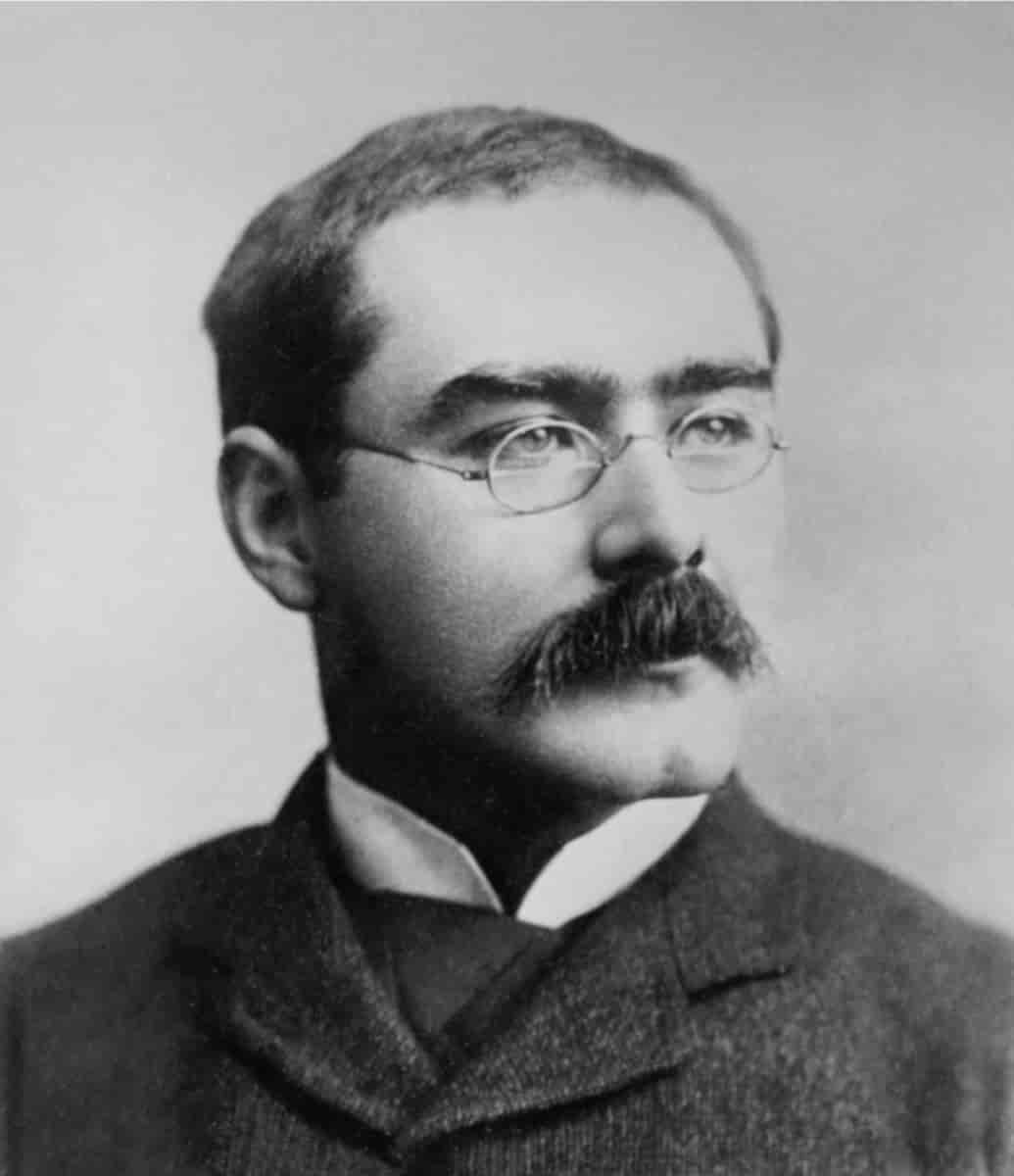

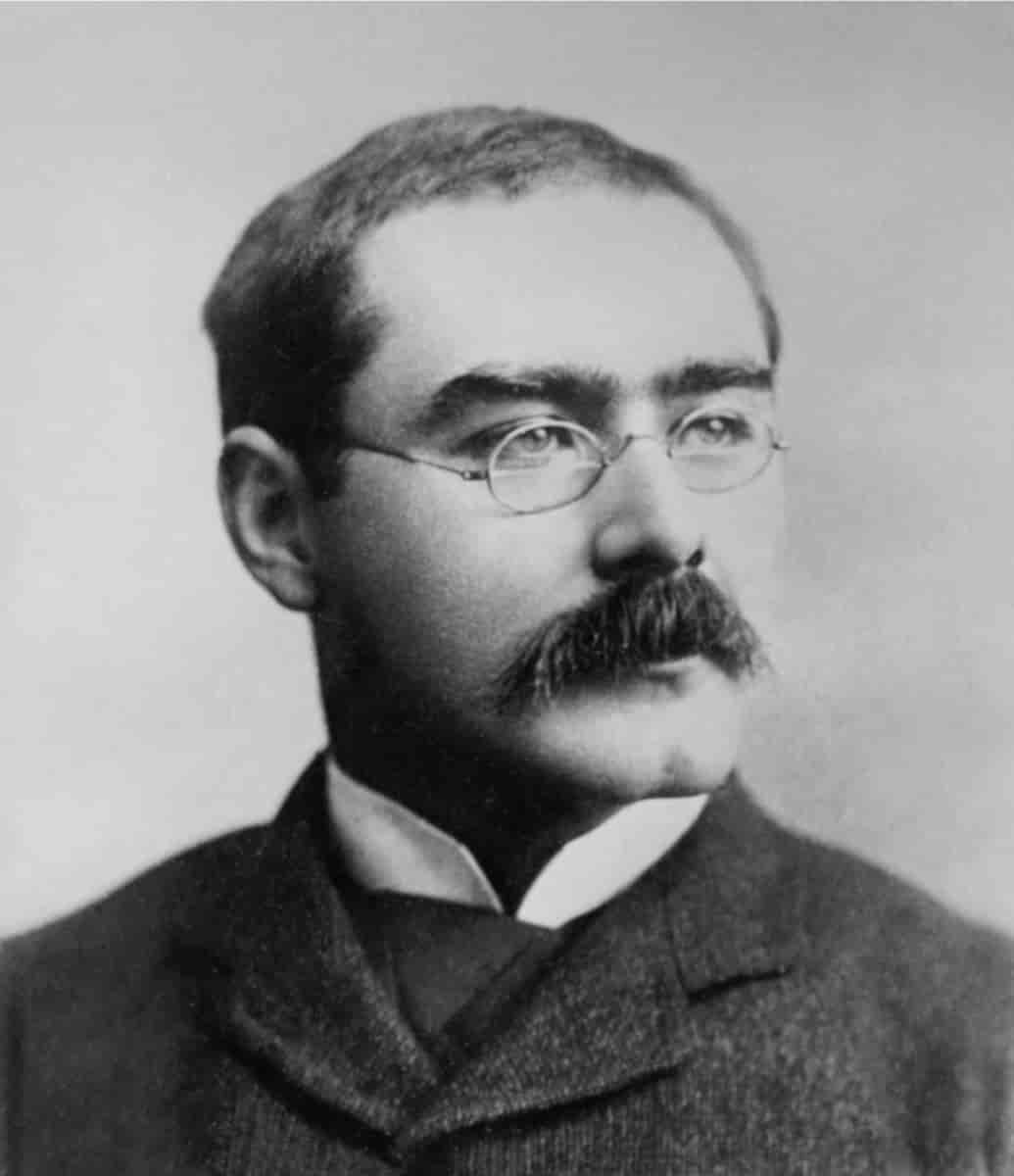

Rudyard Kipling could hardly be less fashionable in these anti-colonial days. He was a promoter of empire. Worse, like Trump, he was a populist. He wrote for the common man.

He has also never been to my taste. His prose seems unnecessarily foggy at most times; he rarely seems to make an interesting point. I won Puck of Pook’s Hill as a prize back in grade school, and could never get my head into it. In both poetry and prose, his upper lip is far too stiff for my Irish Catholic temperament. All that English stuff about doing your dooty and dying at the drop of a hat for king and law. Sounds blasphemous to this Mick.

Yet I cannot deny his immense skill as a poet. In the craft of casting memorable lines, he puts anyone writing today in the shade. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature, the youngest person ever at that time, and the first Englishman.

He is the ultimate “people’s poet.” His poem “If…” for all its weird Englishness remains the most popular poem in England.

I was recently looking again at “The Recessional,” with my students. I think it is his best poem.

Perhaps we ought to see what he has to say. In this poem, at least, I think he does go deep.

The first point I think he makes worth making is that the British Empire is under God’s dominion, and derives its legitimacy by doing God’s work. God is “Lord of our far-flung battle line.” He is “Lord God of Hosts”—of armies.

Kipling is right. To the extent that any government can claim legitimacy, it is because and to the extent that it is doing God’s will. This is more or less the same point made in America’s Declaration of Independence.

Does God then command the armies? Does he play favourites among combatants?

Of course he does. Pacifism is not a Judeo-Christian principle. God plainly favours the Israelites in battle in the Old Testament; the Canaanites, the Philistines, the Babylonians, the Seleucids, the Egyptians, are unambiguously villains.

What is unique about the Judeo-Christian tradition is the idea that God expresses his will and his divine plan through human history. That means in any given war, one side is probably doing his will, and the other side is with the devil.

More broadly, the creation is an eternal war between good and evil. We are to take up our sword and defend the right. Pacifism is simply moral cowardice.

This ought to be clear enough to natural reason. Whenever a fight breaks out, between two individuals, two groups, or two nations, it is almost inevitably an aggression by one party against the other. Why else? Misunderstandings can be talked through. One party merely calculates it is stronger, and can take what it wants.

The current war in Ukraine is an example. No, there are not perfectly balanced rights and wrongs on either side. Russia wanted to control Ukraine, and thought they were strong enough to do it.

And here we even also see the hand of God. Who could have predicted that Ukraine would hold out and begin to advance? A close analysis of history actually does suggest that, given anything approaching equality of forces, the side in the right always wins. This is true because we all have a conscience, and it weakens us when we go against it.

So the question is whether the British Empire was rapacious, or was doing the will of God. This is exactly the question Kipling asks, and struggles over.

Being an Empire by itself does not figure: it is neither good nor bad. There is no moral value in being governed by people with the same skin colour or ethnicity as yourself. The question is whether the British brought better and more moral government than the governments they replaced.

Kipling would no doubt see them as doing God’s work in ending slavery, ending the caste system in India, suppressing human sacrifice, toppling oppressive rulers in Africa who practiced cannibalism, ending interminable tribal wars, and so forth. All of which they certainly did. Along with instituting governing structures and infrastructure that successor regimes have almost never seen fit to discard.

It was no doubt in Kipling’s eyes the world’s police force, introducing and protecting human rights. At a minimum, the case must be made that it was not, that it was oppressive and self-interested. It cannot be assumed.

The usual claim, I suppose, is that Britain exploited the colonies financially, leaving them poorer than they had been. It can certainly be argued that mercantilist policies might do this; but trade generally benefits both parties. And my impression is that the actual numbers do not bear that out.

But this is background. This is not the key message of the poem. It is, rather, that the British might lose their grip on this moral foundation, like “lesser breeds without the law.”

Who are these lesser breeds?

“Gentiles.” “Heathens.” The distinction made is not racial, but religious.

And Kipling is more specific:

Heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard

Kipling is not talking about African tribalists or Amerindian natives. Iron shards are products of the Industrial Revolution, not stone age cultures. Reeking tubes are most obviously found in chemistry labs.

Kipling is warning against “scientism,” the worship of science and technology as our new God. Which is indeed the disease that is currently killing Western civilization.

The prime danger of scientism is that it has no morality. It is “without the law.”

Kipling was writing ten years after Nietzsche had published Beyond Good and Evil and On the Genealogy of Morals, arguing that man had now replaced God and could create his own morality to suit his purposes.

Such boasting as the gentiles use.