On a recent JRE episode, Joe Rogan and Bill Murray reminisced sadly about the counterculture of the Sixties. They read a piece by Hunter S. Thompson that described it as a wave that suddenly broke and disappeared. There was a magical spirit of confidence then that was lost, and both pondered why. We all knew we were going in the same direction, we were in the right, and victory was inevitable. But at the same time, we did not know where we were going.

They seemed to agree that spirit died when the Nixon administration made LSD illegal in 1968.

That might be so; but it seems to me there were still plenty of psychedelics around after that date. And LSD was already illegal in Canada in 1962, and the same counterculture throve in Canada, in the same years. We had the Georgia Straight, and Yorkville, and Rochdale, just when America had Haight-Ashbury and The Village Voice. And our hippiedom died around the same time the American scenes died.

I think it was something else, something that came later. LSD was only a gateway drug. It did not account for everything. There was also that excited hopeful spirit in the folk boom of the early Sixties, in early rock and roll, and in the Beats, before drugs became generally involved. “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive.”

The counterculture was actually the rebellion against modernism. The culture it was countering was modernism and scientism. It began in the old Victorian walkups of the Haight, which were being stripped of their ornamentation to conform to the modernist style: “a house is a machine to live it.” Hell no. In reaction, hippies moved in and preserved the old Art Nouveau ornamentation they found preserved from the general rebuilding of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. And that same Art Nouveau style inspired much of the art of the counterculture. Natural, flowing, organic forms. Avoid geometry and hints of the machine. We are more than machines.

It was a rebellion against the emphasis on STEM in American education in the early stages of the Cold War and the technological race with the Russians; the popular hysteria over Russia getting the bomb, and then sputnik. I recall my college buddy’s Firesign Theatre albums mocking “More Science High.” And we all knew what they were talking about. Science and math were soulless. We wanted “more poetry in the classrooms.”

And what, after all, was the predictable end point of all this emphasis on science and on competition and on material progress? Mutual assured destruction. Our leaders said it themselves.

Hell no; we won’t go.

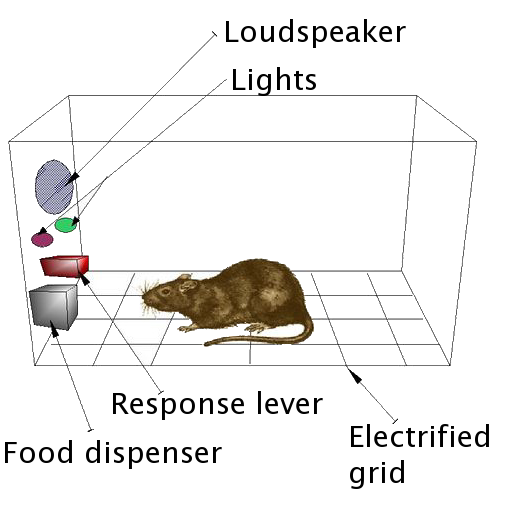

And the apex of all, the arch-villain, was B.F. Skinner and behaviourism. Which saw us all as lab rats condemned to a meaningless life on the exercise wheel. “Beyond Freedom and Dignity.” Skinner said we had no soul.

Psychedelics were significant because they were the disproof of all that. Psychedelics were not fun. They were omore often terrifying. There were inevitably “bad trips.” Why would anyone actually volunteer to, in effect, go temporarily mad.

They were a necessary gateway because they proved there was a world beyond the material. People dropped acid to see God.

But there was of course a contradiction here too: drugs were a material means to transcendence. It was kindergarten. Relying on a chemical was still not making the leap.

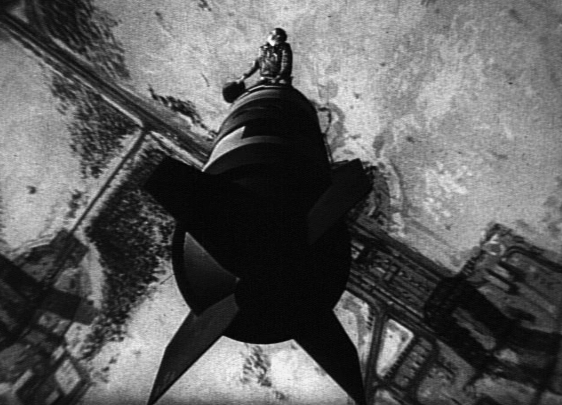

Some made the leap with suicide. Hence Heaven’s Gate. Hence the 27 club. It seemed to make sense. The rocket ship to heaven.

The majority chickened out, and became yuppies. Back to the exercise wheel and shut up.

But the logical move was to religion: the Jesus Freaks, Transcendental Meditation, the Hare Krishnas, the Moonies, those exploring Eastern mysticism. We were heading for a Great Awakening.

And what killed it then was not the banning of drugs; most people lost interest in psychedelics naturally once they’d done the experiment. It was the popular anti-cult hysteria of the seventies and eighties. This was the empire striking back. Waco was stormed. And, of course, Charlie Manson, or the People’s Temple, and other frauds, did much to discredit the cults.

Young people who joined the new religions were kidnapped by professionals hired by their parents and “deprogrammed.” Whether or not the religious groups they’d voluntarily joined were brainwashing them, these professionals certainly were.

That’s what killed it; or at least, threw the rebellion against materialism into a coma for a few generations.

There are signs we see at last a revival. There is a reason people like Rogan and Murray are looking back now with nostalgia. We are beginning to understand we took a wrong turn, and lost something.

I hear strange echoes of the Sixties when I listen to RFK Jr.; and I begin to remember and feel within me the spirit of that age. Although he is talking about food and drugs, his tones are overtly moral and spiritual. J.D. Vance publicly refers to Catholic moral teaching. Candace Owens converts and declares “Christ is king.” The “New Atheists” of a few years ago seem to have been defeated in the public arena. Bishop Barron and William Lane Craig, their conquerors, have become the more prominent public intellectuals. Jordan Peterson is slowly converting in the public eye, and bringing many followers with him.

That the revival seems to be rather Catholic is, I think, significant. Catholicism is the most spiritual and least materialist form of Christianity. It is the home of Western mysticism. No “Protestant work ethic”; no “prosperity gospel”; an emphasis on beauty. And, unlike the cults of the Seventies, it has a well-established system of oversight and authority, however imperfect, to prevent scandal, charlatanry and exploitation.

We may, at last, be achieving liftoff.