|

| War of 1812 Memorial, photo courtesy Ottawa Citizen. Left to right: Indian warrior, Canadian militiaman, Newfoundland Fencible, Canadian Voltigeur, Metis cannoneer. |

I suppose all nations falsify their histories. It is just more embarrassing to see one's own country do it.

I refer to the new monument to the War of 1812 unveiled on Parliament Hill, “Trial through Diversity.”

The title is already a bad sign, isn't it? Diversity is a big current political value. Does it really apply to the War of 1812, or are we snuggling up together in a Procrustean Bed?

So in the present statue, unveiled to mark the 200th anniversary of the last shot on Canadian soil, we have seven semi-symbolic figures, supposed together to express the “diversity” so important for the defence of Canada in 1812. There are both significant omissions from and additions to the historical record here. Both smell bad.

Most notable is the absence of the British Army. As in, the main force involved. Granted, the Royal Navy is here, as it ought to be. And supposedly, the British Army is represented by the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles. The Royal Newfoundlanders, as a unit, are deserving of recognition; and one can see the political need to include the Atlantic Provinces in the display. But this was not a British formation; it was a locally-raised militia force. And its successor unit is a part of the Canadian, not the British, forces.

No doubt the Canadian government sees no political capital to be gained by honouring a foreign army. But this is ungracious, and, in the end, unnecessary. In fact, a huge proportion of the British soldiery who served in Canada in 1812 ended up staying and settling here, so that their descendants are indeed Canadians.

The second omission is the native contribution. Granted, there is a native figure included, but he is inaccurately posed. He is not shown with a weapon, but pointing the way—as if the native contribution was primarily the job of scouting. The faithful Indian sidekick, like Tonto and the Lone Ranger. This amounts to a radical devaluation in comparison to the reality, which is that native arms under Tecumseh, the Six Nations, and the Mohawks if the St. Lawrence were crucial to the entire affair. It is rather as if a British soldier were portrayed as unarmed and pointing the way for an American GI to commemorate the Second World War. Would that convey a true picture?

Now for the odd additions: the most egregious, and most political, is the woman bandaging the hand of a Voltigeur. Of course, to appease the feminist lobby, they had to work in a woman somehow. They figured they could not credibly pretend that women were fighting, so they threw in a nurse. There must have been nurses, right? Unfortunately for them, it being a long time before Florence Nightingale, there weren't. Each outfit was accompanied by a surgeon for the succor of the wounded; who was, of course, always male.

Then there is the odd anachronism of a Metis firing a cannon. Technically speaking, there must have been a reasonable number of “Metis,” that is, people of mixed European and Indian ancestry, fighting in the war. But they would not, at this period, have thought of themselves as Metis. That concept, and that distinct culture, emerged later, on the Prairies. At this time, they would have been considered, and would have seen themselves as, either French Canadian, English Canadian, or Mohawk, Wyandote, Ojibway. The “Metis” cannoneer has been thrown in for the sake of the historical illusion that Western Canada was somehow involved in the conflict.

To my mind, it demeans the heroes actually involved in the conflict to ignore some of their closest comrades, and then to make them share their honours with strangers who were not there.

Perhaps the larger problem is the idea of putting up statues to groups of people rather than to individuals. This, after all, is the sort of thing that characterizes totalitarian regimes, and perhaps there is a reason for that: lusty, smiling peasants raising their sickles in unison. It encourages groupthink, and represses ideas of individuality. That makes people easier to manage. Because the figures being portrayed are fictional to begin with, their characters and imaginary deeds can be manipulated freely by the powers that be to suit their present needs, and no real deeds or actual characters can be cited to serve as a check on their actions. It becomes so inconvenient, for example, to have someone point out that Martin Luther King was actually against racial preferences.

|

| Secord warns FitzGibbon of the American advance at Beaver Dam. |

If you really want to celebrate the female contribution to the War of 1812, you could, of course, put up a statue of Laura Secord. What is wrong with Laura Secord, but that her real life and real views might come in conflict with the needs of modern feminism? To celebrate the native contribution, why not a statue of Tecumseh? To celebrate the British regular, there was a chap named Sir Isaac Brock some of you may have heard about—not to mention sadly underappreciated but admirable working-class soldiers like James FitzGibbon. Unfortunately, FitzGibbon had the bad taste not to die young, so that he left many known opinions behind him.

|

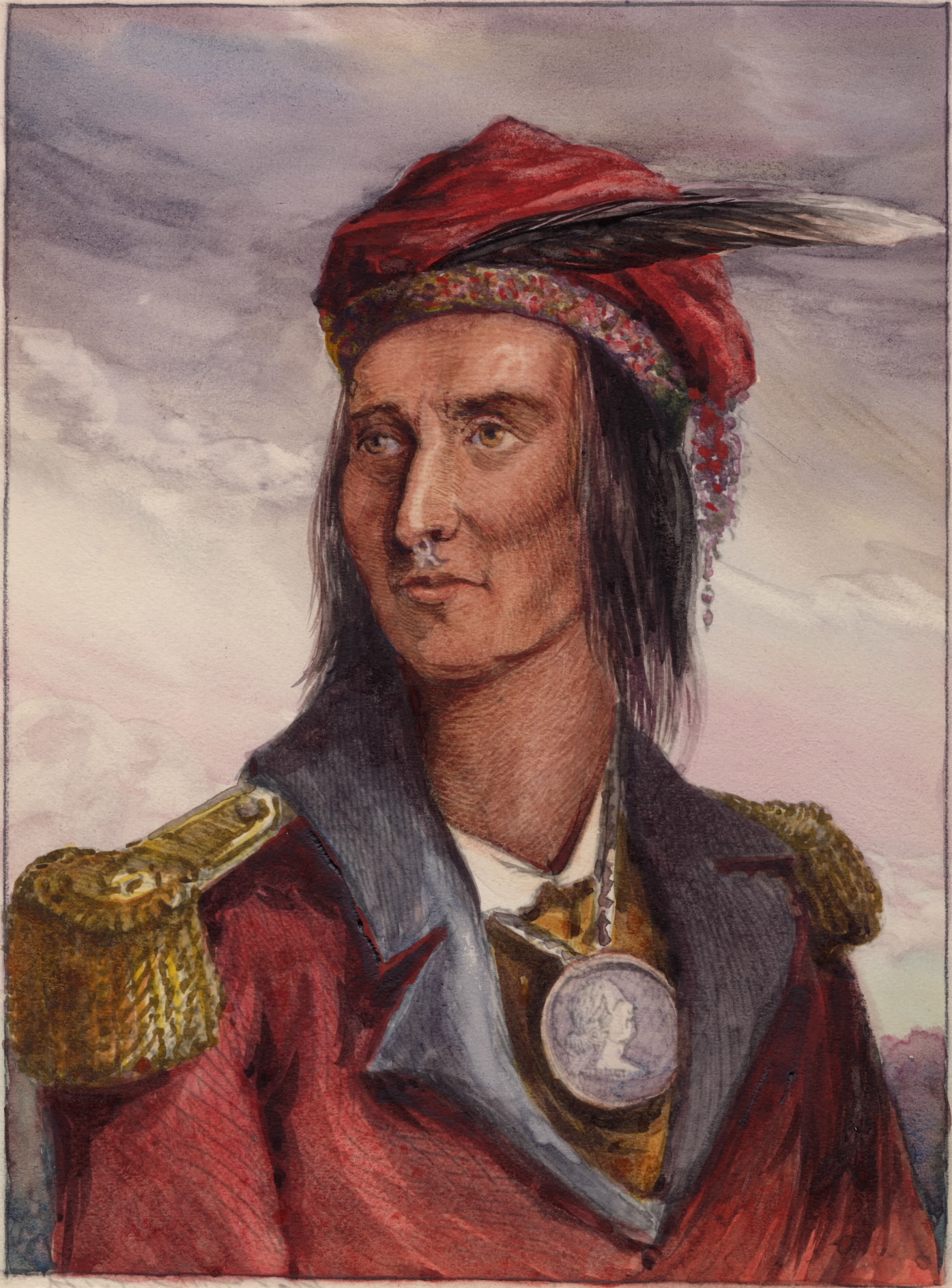

| Tecumseh. More than just a handy index finger. |

No comments:

Post a Comment